As the name suggests, the online viewing room is an attempt to bring the gallery experience online. For many dealers and fairs, they have been successful in propping up revenues whilst doors have been forced shut by the coronavirus. Earlier this month, for example, many reported stronger than expected sales through the Frieze New York Viewing Room, with mega-dealers and small galleries alike selling six-figure works.

But is there something about these rooms on screens that makes them anything more than online shops, places to show photographs of artworks and transact via the internet? Is the term online viewing room an oxymoron? Sometimes it feels like the commercial art world has trouble calling a spade a spade, and this looks like what’s happening here. Artsy’s new CEO Mike Steib, a self-identifying art world outsider, commented in an interview with The Canvas that

“online viewing rooms are essentially just websites. There’s nothing groundbreaking about them.”

I’m inclined to agree. I also think that, as long as we are limited to experiencing artworks and exhibitions online, there’s one respect in which – no matter how far the technology evolves – these experiences will never be comparable to that of being in a gallery. The online viewing room changes beyond recognition the phenomenological relationship between our bodies and the exhibitions that we view in them.

Experiencing through the body: Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology

Phenomenology is an area of philosophy that looks at our experience of the world as human subjects. Maurice Merleau-Ponty was a 20th Century phenomenologist who claimed that the body is inescapably at the centre of this experience. We can’t think our way out of the fact that we live and perceive every day through our bodies. I am always, as he puts it, “first of all surrounded by my body, involved in the world, situated here and now”.

In terms of how we experience what is around us this means that, rather than studying and understanding things first and foremost with our minds, we experience them in a pre-intellectual way, through our bodies’ interactions with them. That is to say “the experience of phenomena is not an act of introspection,” but one of material engagement. Our relationships with the world are physical and practical, led by the intuition “I-can” rather than “I-think”. When I look around the room I’m sitting in I don’t intellectually digest each object surrounding me. I simply understand them as “props and guides of a practical intention.”

For example, when I see a pen I don’t have to go through the motions of deducing what it is, starting with ‘stick,’ then ‘instrument,’ then ‘writing instrument’ and finally ‘pen’; my hand, which has already held so many pens in the past, can simply grasp it and begin to write.

I can’t view myself as a detached thinker reasoning my way through my various engagements with things in the spaces where I find myself. I am, to borrow two more of Merleau-Ponty’s terms, a “habit body” with a bank of physical knowledge that guides me through the “acquired worlds” that I inhabit.

The habit body online

One of these acquired worlds is the gallery. This is a space that I have come to understand, through all of my past experiences of galleries as a body-subject, to be a place for looking at, thinking about and generally enjoying artworks. Guiding this practical intention is a combination of props and guides that I experience here: the cold of an ice-bucket fresh beer bottle in my hand, the smell of oil paint and freshly drilled plaster, the glow of LED lighting overhead.

I don’t need to make a mental note of where I am and what I’m supposed to do here, just like I don’t have to re-learn what a pen is each time I come across one. My habit-body reads all of these sensations and gears itself for engagement with artworks, which has come with them so many times before. But what happens when this acquired world is no longer available to me?

Since the beginning of lockdown, I’ve found my body’s bank of physical knowledge challenged repeatedly. I’m trying to work from my bedroom, a space that I have until now experienced as one for relaxation. After work, I’m on Zoom calls trying to have pub garden conversations whilst sitting alone on my sofa. Like many others, I’m spending my time trying to do exactly what Merleau-Ponty has told us can’t be done and override the physical cues and guides that surround me. My brain is trying to tell me what I’m experiencing rather than leaving my body to figure it out.

The same thing happens in an online viewing room. If I want to experience the work on show as I do in a gallery I must by sheer power of will transcend my physical self, sitting at a desk hunched over my laptop, and mentally enter the gallery space. In other words, my mind needs to be somewhere that my body isn’t. This, Merleau-Ponty would say, is impossible. We experience through our bodies and, for as long as we can’t physically occupy the two spaces at once, we can’t “bring together [the] discrete experiences which occupy several points of time” – in this case, the experiences of being on a website and being a gallery.

What does this mean?

The fact that this problem arises from the inescapable physical fact that an online viewing room is not an actual room makes it seem insurmountable. No matter what galleries do to make the viewing room experience feel more authentic, this fact will endure. Any efforts they do make – virtual tours, VIP-only openings, VR headsets – will only serve to encourage our brains’ efforts to override the reality that our bodies are experiencing.

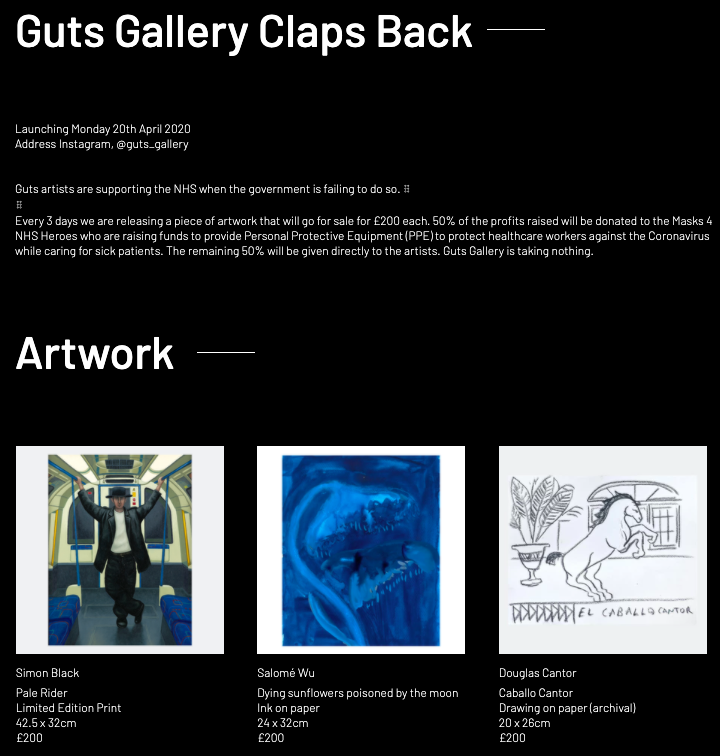

We need to treat likes alike and unlikes unlike. That means being honest about the fact that online viewing rooms aren’t viewing rooms and, as such, will never meaningfully reproduce the experience of being in a gallery. Like the rest of us, dealers are still finding their feet and trying to muddle along under these new conditions. The best thing we can do is to understand and be honest about the benefits and limits of online viewing rooms.

For galleries, they are web pages where they can continue to display and sell their artists’ works. For visitors, they are web pages where we can look at, learn about and, for some, buy artworks until galleries re-open. That’s all. And for now, that’s enough.