Most people can agree that chucking soup at old paintings isn’t doing much to heal humanity’s relationship to the planet. However, performative spectatorship may be something that can heal our relationship to the museum — one that American artist Carol Bove asserts is fraught with violence and grief.

In her current exhibition La Genevoise at Geneva’s Museum of Art and History, Bove —with free rein of the museum’s extensive collection of art and archaeology— proposes a new “way to be” inside a space historically characterised by ‘civilised’ behaviour, (peculiar) etiquette, and the anthologised arrangement of material culture — but not necessarily accessibility.

Proustian and spacious with fine finishings throughout, the hundred-and-fifteen-year-old museum is one of Switzerland’s largest and feels as conventionally legitimate as a museum can. All the markers in the Beaux-Arts building are there: Byzantine style mosaic floors? Check. Ornate balustrades? Check. Gentle yet unrelenting aura of imposition? Check.

Ignore the Francophonic chitter-chatter in the air, and one could mistake its lofty wings for those of New York’s Metropolitan. What museums like this have in common, if not all museums to some extent, is a kind of confinement. One that severs the relationship between the visitor and the objects as well as the objects from one another.

Stripped of any original use value to serve aesthetic duties and often plucked out of biological or experiential rationalisation, precious relics become exiled to the great museological vacuum. Sequestered behind glass, velvet ropes, not to mention hidden away in storage crates — it’s no wonder Robert Smithson described the museum as a place where artworks go to die. Or, according to Foucault, not a temple of culture but a prison for it.

So what exactly is the role of the human in such a regulated, venerated, and curated space?

Well, the art and artefacts we choose to exhibit consecrate the record of our existence, give a sense of security, pride, and perhaps even meaning of life. However, once the objects traverse the museum threshold, they become something else. Something that has less to do with the human being and more with the institution. It is this warped ontology of objects and their frustrated place amongst the living that Bove interrogates, plays with, and even seeks to repair in the museum’s fifth edition of Carte Blanche.

Started in 2021 by Swiss museum director Marc Olivier Wahler at the end of his hefty two-year directorial probation period, the Carte Blanche — a kind of curatorial invitation — is a prompt that invites a selected artist to dig through the museum’s collection of over 650,000 objects in order to generate a fresh perspective of the collection. The resulting exhibition is a cross between artistic intervention and contemporary evaluation of Geneva, of Switzerland, and of the architecture of Western European society.

For the first half of each year since, the museum’s galleries have been transformed through the eyes of the artist; an approach that allows MAH’s visitors to access works through a fresh lens and uncover parts of the collection that may have been in storage for decades. It is one of many instances where Wahler’s forward-thinking programming has sought to dismantle museums as domains for the elite — an agenda that has not always been well received.

Bove’s restrained assemblage of objects represents the development of material culture in the Genevan region. Starting along the perimeter of the museum’s atrium with the Palaeolithic era, the selection also takes into account the absence of representations. Entire rooms are left vacant, plinths unoccupied. Except, how vacant are these rooms really, considering the high degree to which they have been finely, if not excessively, finished?

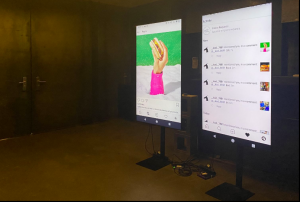

Scaled to equate one linear meter to seventy years of local history, Bove selects artefacts to be displayed in chronological order. What’s readily apparent about the collection though is not the items themselves, but the set of “shadow” replicas shown parallel. 3D printed in black polymer and identical in size and shape, the replicas are mounted at graspable height from long black soldier beams with the intention that they be touched, fondled, and observed up close and personal.

“I hope everyone had a chance to touch things,”

Bove says, going on to

“wonder if people who have been trained in seeing museums and not touching anything and being ‘good viewers’ — if touching exposes them to grief…to be able to do this thing that we really longed for without knowing it.”

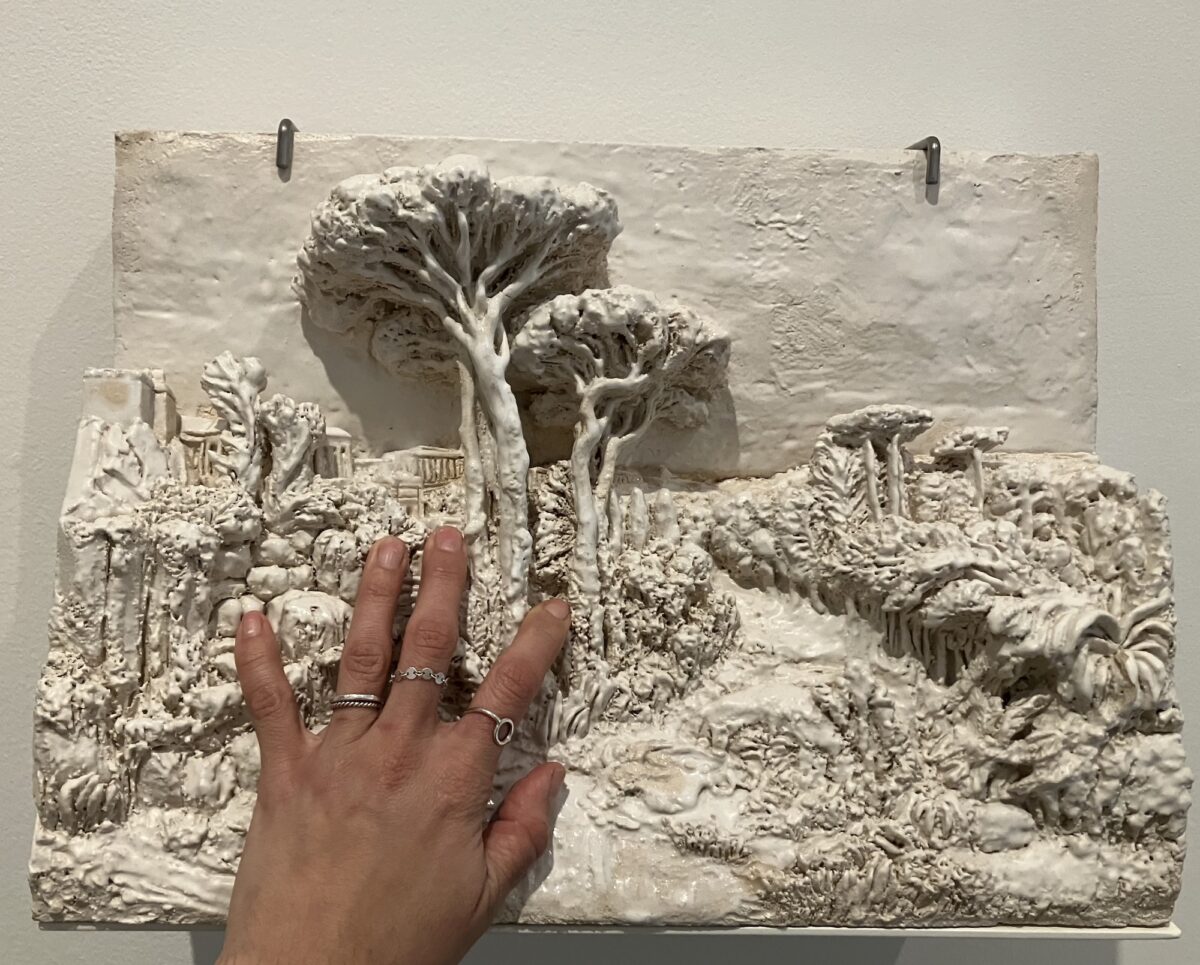

Turning the corner, a central gallery houses furniture and is lined with ceramic reproductions of Old Masters paintings. Intended to be touched, the highly detailed reliefs are authored by the late Quitterie Ithurbide, a ceramicist from Versailles who sculpted reproductions of well-known artworks for the visually impaired from 2009 to 2020. Early in the research phase, Bove asked if the museum had versions of paintings rendered in 3D for blind people. Unbeknownst to Wahler, the reproductions existed but had been packed away in storage for many years.

Unlike the shadow replicas, the ceramics are unique items; their gnarled, glossy surfaces tell the story not only of the painting they represent but also of their very formation: created in tandem with a museum mediator, certain details are emphasised to convey depth, distortion, and narrative. Usually intended to be placed alongside original paintings as an aid, Bove has bypassed the originals, allowing Ithurbide’s works to stand alone.

By passing on the title of “artwork” to a formerly functional object, the ceramics mimic the process of museological decay — but with one critical difference. Much like the objects stood adjacent in the centre of the same room (chairs, armoires, and small wooden household items), they have been elevated but not relinquished of their original use. Unlike artifactual relics, the ceramics can at least still be touched.

Ithurbide summed it up in an interview over six years ago, stating that “touching the ceramic, unlike the resins or 3D printing, can be sensual.” In short, the ceramics have no shadows.

While it may just be a semantic question of sensual versus sensory, it seems like polymer replicas function as supplemental tools — another point of entry to go along with written texts and audio guides — but the emotional or human experience associated with viewing, or in this case mediating, art is missing.

Something tells me that wrapping my hand around a lump of polymer doesn’t quite quench the primordial thirst for feeling the hollowed density of a hundred-year-old bear tooth or the cool conductive qualities of pure stone. While the contact to these “shadows” assuages a frustrated, deviant fantasy of accessing the inaccessible, there is a materiality missing from the very material itself, like Indiana Jones swapping a golden idol for a bag of sand. In the end the audience may, as always, decide for themselves. Does touching a shadow bring visitors closer to the works, or does it magnify the distance between them?

Carol Bove, Carte Blanche– La Genevoise – June 22nd 2025, Musée d’art et d’histoire