Frieze London 2019 – the more contemporary half of the fair – seemed in good health this year. Here are seven works that interested me. We start uncomfortably:

Kaari Upson: Seven at Sprueth Magers, Berlin / London (top image)

Kaari Upson does trauma powerfully. She was born in the San Bernadino, east of LA, a challenged community in which crystal meth started out, and which follows a policy of felling trees on account of wild fires. Returning to her childhood home, she found only one tree standing: she casts it in a form which merges trunk and flesh – including the shape of her mother’s knee. Why seven tree-legs, I asked? It’s just a better number, I was told, then than six or eight…

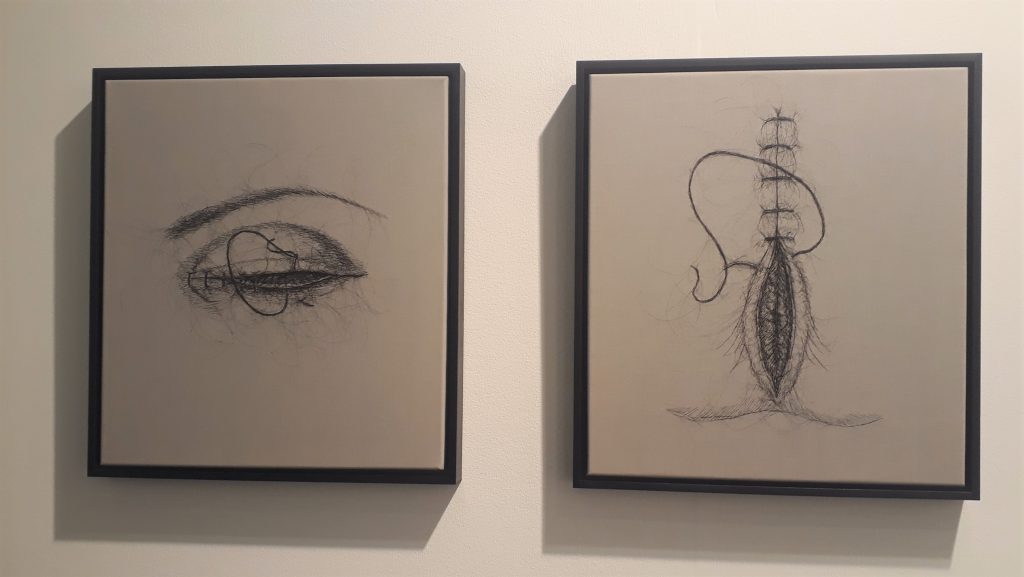

Angela Su: Satin Stich and Feather Stitch 2019 at Blindspot Gallery, Hong Kong

Angela Su demonstrates different embroidery stiches in the special feature section ‘Woven’. If that sounds domestic, her medium and subjects are charged: human hair forms images of body parts sewn up in political protest: here the eyelids and vagina. Moreover, these works were made during the three recent months of protest in Hong Kong.

Claudette Schreuders: In the Bedroom, 2019 at Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

The South African artist works mainly in wood, but has cast these figures, on the edge of cartoon and children – in bronze, with the skin painted a pallid grey which heightens the unease they generate. It’s from a series which investigates how coupledom has been shown throughout art and broader cultural history. If this is sex, it looks awkward enough to be inappropriate – and carries a political overtone in a nation in which public and private are often inappropriately blurred.

Thomas Demand: Towers, 2019 at Matthew Marks Gallery, New York

Thomas Demand typically takes photographs which at first glance reproduce real scenes, often politically charged, but on closer inspection are evidently of models made of card. His latest series plays with our knowledge of his practice by taking – from a dramatically low viewpoint – a photograph of an architect’s model for a building which remained unconstructed (here a proposal by Gio Ponti). Demand doesn’t need to make a cardboard version, because there never was never another version.

Sterling Ruby at Gagosian Gallery, various sites

One of the best stands was an obvious one: Gagosian’s solo of Sterling Ruby, complementing his simultaneous solo show at the Kings Cross gallery. Here ‘Helios Boat’ 2019 takes centre stage, a large ceramic made by filling a basin form with cast-off and broke scraps and then firing the entire assembly together. Ranged behind are some of the WDW (2016- ) series of paintings which suggest windowscapes using cardboard, patterned fabric and paint. The whole proposes an archaeological view of Ruby’s studio practice.

Nicholas Pope: Yahweh and the Seraphim, 1995 at The Sunday Painter, London

Bu the biggest ceramics on view, my pick of the project section, and top revival aside from Frieze Masters, came from Nicholas Pope. The Sunday Painter recently retrieved this set of seven 4.3 metre high ceramics, made in three sections each in a giant kiln, from many years of storage in his studio. They were to form part of a non-denominational chapel, but have their own authority.

Claudia Comte: Quarter Circle Painting (from peach to pineapple), 2019 at Koenig Gallery, Berlin / London

Swiss artist Claudia Comte often combines wooden sculptures with abstract wall paintings. This attractive painting operates independently, but there is a twist: the four quarter circles are separate, and so can be reconfigured in other arrangements, including to make a more orthodox abstract tondo.

There are fewer ‘extra-creative’ / ‘gimmicky’ stands than in some years. Perhaps the solo show is the commonest ‘risky’ approach, and outside of the special sections, whihc encourage that, I also enjoyed Jonathan Lasker (at Timothy Taylor), Ivan Morley (at David Kordansky) and Bernard Piffaretto (at Kate MacGarry). I’d say look out, too, for the overall excellence of Max Hezler, Seventeen, 303, Casey Kaplan and Hyundai

Art writer and curator Paul Carey-Kent sees a lot of shows: we asked him to jot down whatever came into his head