Art Basel’s online viewing rooms can be visited until 26 June. There is plenty of trouble in the world for that art to reflect: not just the virus, the economy, wars, terrorism and global warming but also bad attitudes. Here’s my selection of work which addresses the anti-discriminatory agenda so effectively foregrounded by ‘Me Too’ and ‘Black Lives Matter’…

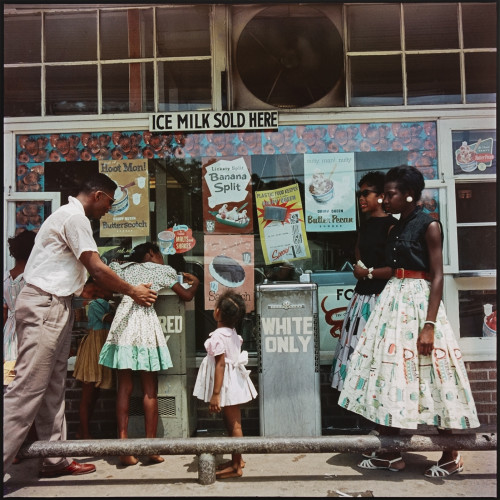

Gordon Parks: At Segregated Drinking Fountain, Mobile, Alabama, 1956 – Archival Pigment Print, 109 x 109 cm – at Alison Jacques Gallery, London (top)

Pioneering African-American photographer Gordon Parks (1912-2006) documented culture and everyday life from the early 1940s to the 2000s. This is from the series ‘Segregation in the South’, which presents marginalised lives and associated injustices quietly, yet consistently with Parks stating: ‘I saw that the camera could be a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs’. The motor for that is the creation of empathy: he held that ‘it is the heart, not the eye, that should determine the content of the photograph’.

Hilary Harkness: Multi-Vortex National Disaster, 2020 – gouache on twelve ‘Liberty Series’ U.S. postage stamps, 6.7 x 10.2 cm at P·P·O·W, New York

This tiny painting on stamps from 1959 might have been easily overlooked at a physical fair but appears appropriately monumental online. Of her ‘US Issue’ series altering stamps commemorating Andrew Jackson (President 1829-37), Hilary Harkness says: ‘Whenever I hear about ‘the good old days,’ it makes me want to redirect the flames of racism and discrimination that are ravaging black communities today. I want to burn that fucking privileged nostalgic amnesia down to the ground. These Jim Crow Era stamps commemorate Andrew Jackson’s plantation home ‘The Hermitage’ where he enslaved 300 people. To me, it’s a symbolic missing link between the wrongs of the past and the present. It felt only right to paint in the flames and smoke that I’ve been seeing ever since I bought them.’

Kehinde Wiley: Rumors of War, 2019 – patinated bronze with stone pedestal 835 x 777 x 482 cm – at Sean Kelly Gallery, New York

Kehinde Wiley’s monumental sculpture is from an edition of three, the first of which was unveiled in Times Square, New York last year and is due to be permanently installed in Richmond, Virginia. Wiley subverts the visual rhetoric of the South’s many confederacy monuments by presenting not the white general as war hero but a young African-American subject dressed in urban streetwear. He states that ‘Rumors of War attempts to use the language of equestrian portraiture to both embrace and subsume the fetishization of state violence.’

Do Ho Suh: Public Figures, 1998 – Stone and bronze, 284 x 209 x 275 cm – at Lehmann Maupin, New York / Hong Kong / Seoul

This is an old work given fresh relevance by current statue-toppling activity. Do Ho Suh says he ‘displaces radically the site of the (heroic) individual by taking the figure from above to below the pedestal, reducing its size, making it anonymous, and multiplying it.’ Moreover, the online presentation includes an animated version, in line with Suh’s original conception of mechanising the figures so the sculpture moved, challenging the notion of site-specificity and the authority granted to permanence.

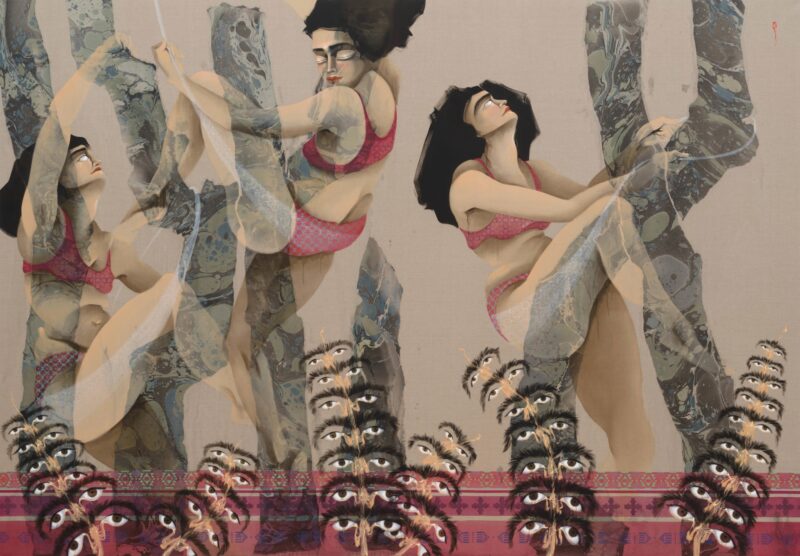

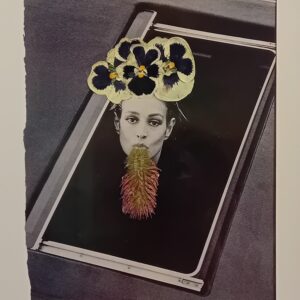

Mickalene Thomas: Hot! Wild! Unrestricted! , 2009 – Chromogenic Print, 61 x 76 cm – at Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Mickalene Thomas says hers is ‘unapologetically the gaze of a black woman looking at black women’, a gaze which she developed by photographing herself as women she idolised, looking for ‘a different way to perceive beauty – not just the surface but also the action – how they define themselves and how they persevere’. Here she gives equal prominence to the orgy of patterns against which that attitude is struck – Thomas creates backgrounds which allude to both the tradition of studio portraiture in African photographic history and the 1970s lifestyle of her glamorous mother, a central muse in her work.

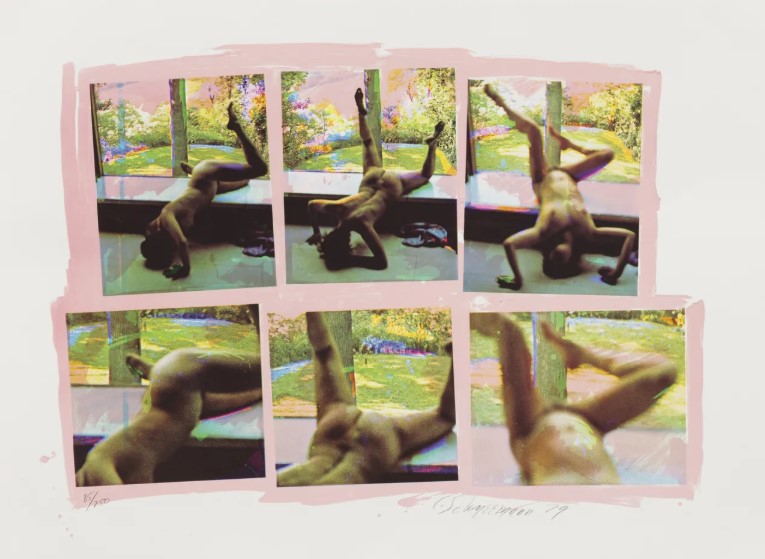

Carolee Schneemann: Forbidden Actions – Museum Window, 1979 – Photo silkscreen on paper, 82 x 112 cm – at mfc-michèle didier, Brussels / Paris

This reproduces six photographic documents of a guerrilla performance at the Kröller-Müller Museum, Netherlands. Schneemann waited for the attendants to change shifts and quickly disrobed for a series of nude actions in the gallery. She described the project as an effort ‘to take the nude off the wall, in a way to de-sacralize or re-consecrate this iconography.’ As Mickalene Thomas says, it’s about the action, not the surface.

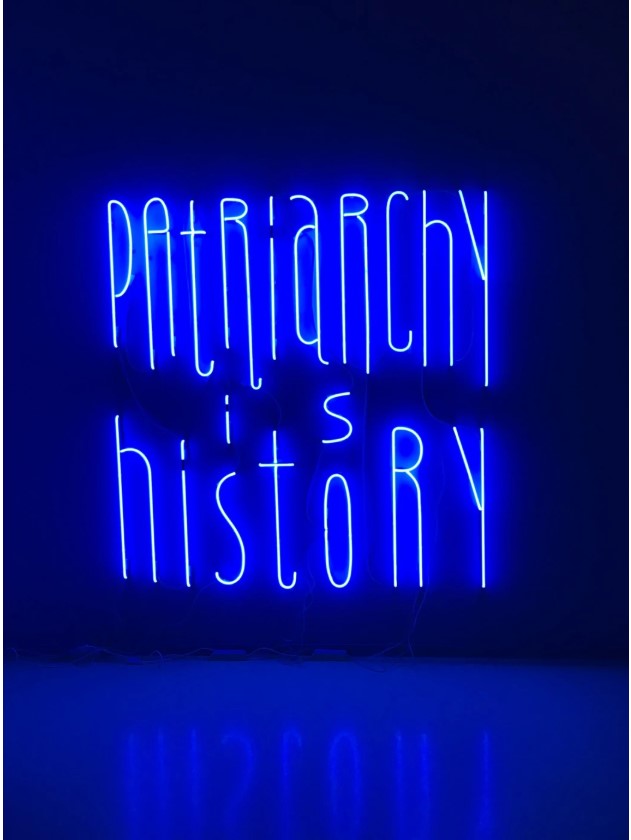

Yael Bartana: Patriarchy is History, 2019 – neon, 198 x 156 cm – at Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam

This seemingly simple statement, developed out of collaborative workshops with a group of female activists from Sao Paolo, resonates with ambiguities. Is it simply recognising an historical reality, or optimistically declaring that patriarchy is already restricted to the past? Or is it set in the future, in which case how many years ahead? Whatever, the gallery declares that ‘the work acts as a symbolically combative agent in the struggle against the mechanisms that shaped the history of our world’.

Art writer and curator Paul Carey-Kent sees a lot of shows: we asked him to jot down whatever came into his head