I spoke to Tate Modern curator Fiontán Moran two months ago on preview day of the hotly anticipated Andy Warhol blockbuster show, the first Tate Warhol exhibition for almost 20 years, before an unprecedented global pandemic meant it would have to close shortly after opening. In fact, the day I interviewed Moran was the last time I ventured out of my neighbourhood before Covid-19 cast a dark shadow over the globe like an unstoppable Tsunami, forcing entire cities into lockdown, shutters going down on museums, galleries, theatres, restaurants, offices, café’s and places of worship as we retreated into our houses like tortoises into their shells.

Enforced self-isolation put an abrupt stop to all group gatherings including cultural activities, theatre, live music and exhibitions, with many museums and art galleries responding by creating virtual exhibition experiences or online museum tours. What would Warhol, the founder of Pop Art have made of this strange scenario? He probably would have spent self-isolation on Snapchat or Instagram. One of the most significant artists of the 20th Century, Warhol embraced popular culture and fame, prophesising our present-day obsession with celebrity and the 15 minutes of fame offered like a poisoned chalice through reality TV, Instagram and Snapchat filters. Warhol was the first truly multi-media artist, starting out as a graphic artist and illustrator in advertising and magazines, before breaking into blue chip galleries with his Brillo box sculptures and canonised images of everyday consumer objects such as soup cans and Coca-Cola bottles. He bridged the divide between art, advertising, commerce, mass media, celebrity and hyper-consumption, not only making the iconic screen-prints of movie stars and beautiful people with which we associate him, but also creating a TV show, managing a band, publishing a magazine and making experimental films that still influence artists and filmmakers today.

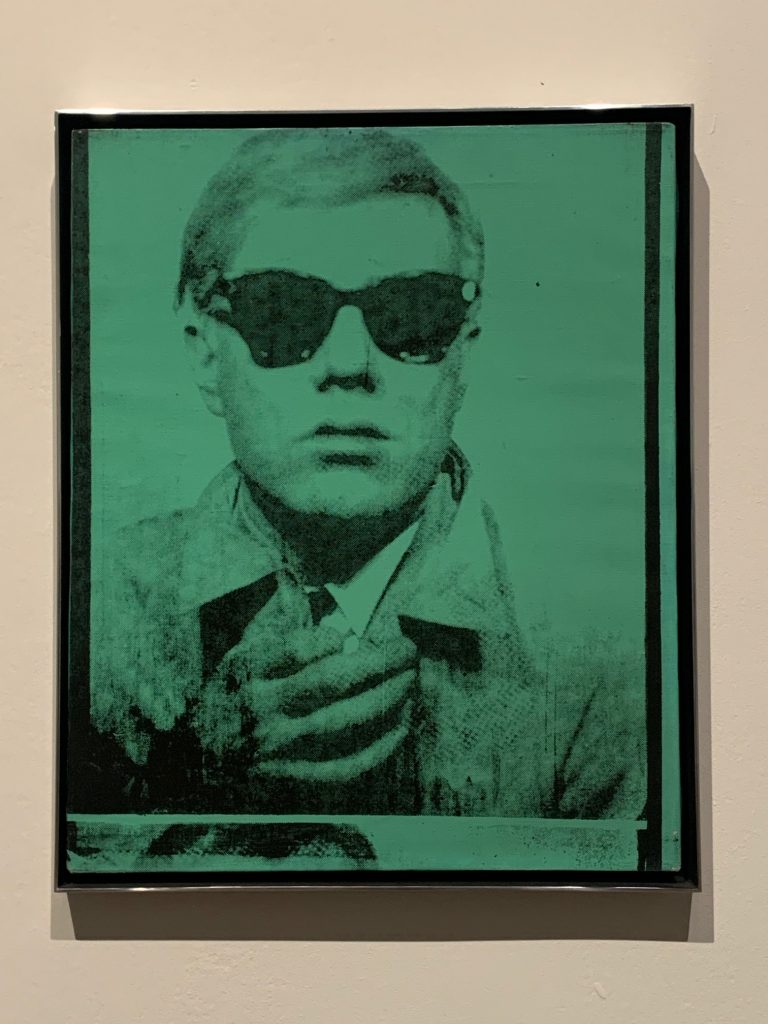

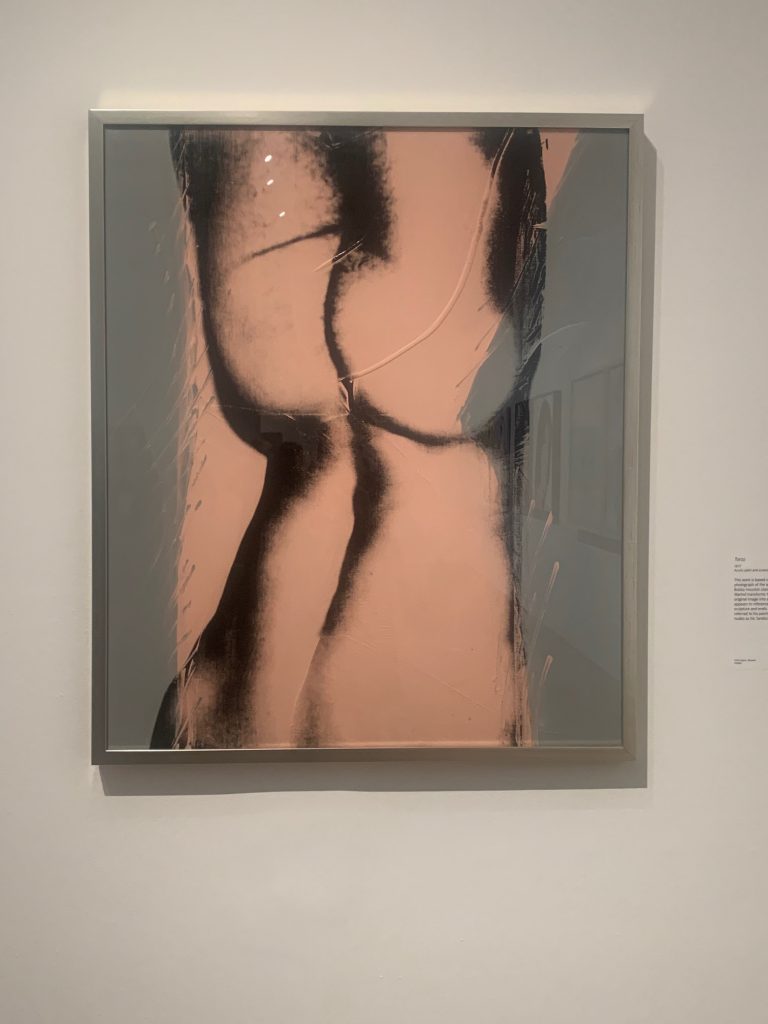

I was fortunate to see the exhibition in the flesh, and it didn’t disappoint. Although I’ve seen plenty of Warhol screen-prints and many of the iconic pop art pieces from the 1960s, the Tate show delved deeper into the man behind the carefully curated image, starting with his roots as the son of Eastern European immigrants who moved to New York in search of the “American dream”, and examining his LGBQTI identity and how it shaped his world view and consequently his work. Seen through the lens of his devoutly religious Catholic childhood, his fluid sexuality and his love of American consumer culture, Warhol’s artistic output is imbued with more meaning.

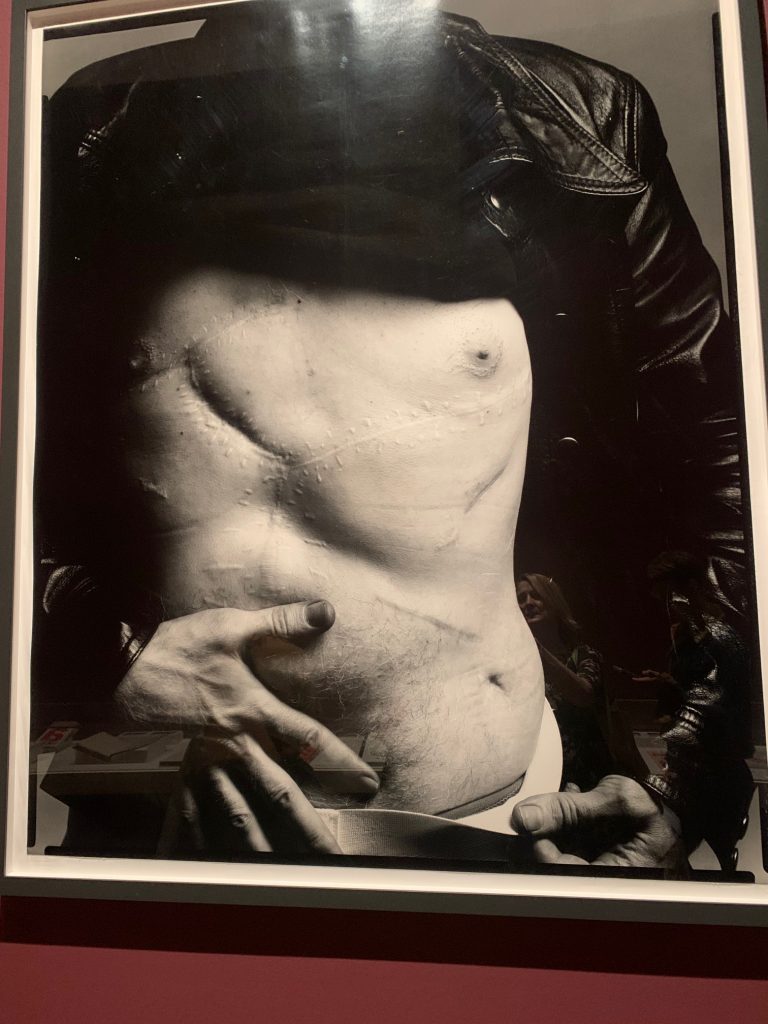

As Tate Modern’s Director Frances Morris said at the press preview, the exhibition promises to “Give us a chance to challenge some of those assumptions we have of Warhol as a person and an artist.” Andrew Warhola was born in Pittsburgh in 1928 to working-class parents who had immigrated from Slovakia to the USA. He moved to New York in 1949, dropping the a from his surname to become Andy Warhol, and finding work as a commercial illustrator before infiltrating the fine art scene with his imagery of American celebrity and consumer culture. There are some rarely seen works on display, including a group of 25 works from Warhol’s ‘Ladies and Gentlemen’ portraits of black and Latino drag queens and trans women, shown publicly for the first time in 30 years. The exhibition culminates with one of Warhol’s final works – ‘Sixty Last Suppers’ – commissioned in 1986 and inspired by Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Last Supper’. Following an exhibition of the series in Milan, Warhol returned to New York where he checked in to hospital for gallbladder surgery, and although the operation was a success, long-term poor health which had plagued Warhol since he survived an assassination attempt in 1968 by Valerie Solanis, led to heart failure and his premature death on 22 February 1987 at the age of 58.

Warhol fans can see the Tate Modern exhibition on BBC iplayer in part 1 of a “Museums in Quarantine” series. Art critic Alastair Sooke took a tour of the exhibition with curator Gregor Muir, who explained that one of his motives was to expand the exploration of Warhol’s oeuvre and not only focus on the iconic Pop Art. Although the exhibition can be viewed on iplayer and online, a virtual viewing doesn’t allow Warhol fans to experience the Silver Clouds room, a gallery with silver-foil lined walls, filled with giant silver helium balloons, or to experience the psychedelic multimedia room where the Exploding Plastic Inevitable was recreated.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m000hqml/museums-in-quarantine-series-1-1-warhol

The Tate website offers a virtual exhibition tour with exhibition curators Gregor Muir and Fiontán Moran discussing the exhibition, and a chance to explore the show room by room: https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/andy-warhol/exhibition-guide

Lee Sharrock: Can you tell me a bit about the ‘Ladies and Gentlemen’ portraits, which have hardly ever been exhibited together as a group.

Fiontan Moran: They’re from a private collection and the collectors haven’t shown them for 30 years. The descendants of the man who commissioned them and exhibited them originally have loaned them. He sold a few over the years, but when he died the remaining collection of 25 portraits went to the heirs.

LS: There are some really iconic images like the Marilyns, the soup cans, Coke bottles and Elvis. But I wasn’t so familiar with the ‘Ladies and Gentlemen’ series. Obviously, we know he was really ahead of his time, but some of the themes and communities he was documenting then really seem to resonate now, like the trans and gay communities. I don’t think many people were documenting those communities at that time.

FM: Although Warhol in his films especially often featured drag queens like Candy Darling, so he was associated with those kinds of communities, but the Ladies & Gentlemen series was actually commissioned by an Italian art dealer who said he wanted Warhol to portray drag Queens. Some people questioned the ethics of that series, because Warhol didn’t know any of the subjects personally. So it’s a slightly different relationship to Candy Darling, so it has a more complicated history. I think personally what’s very special about that body of work, is it’s a community that wouldn’t have been seen around fine art at all, in photography or painting. And now through more research people are able to uncover more information about their identities. So in a way it was an opportunity for us to think about the representation of trans people in art and the difficult lives they may have led.

LS: Yes because they’re still quite under-represented, so it’s quite unique that he was doing that.

FM: Yes, I think across his whole career, he had quite a democratic approach to subject matter. Although people associate him with being commercial, and some people say he was manipulative in terms of The Factory era, I think his general approach was quite open and he was quite welcoming to different types of people. I think that’s why a lot of people were drawn towards him. That’s not to say that everyone enjoyed The Factory and had a great time, but I think he himself was some that was interested in people generally.

Me: It shows it’s not only movie stars he was interested in.

F: He obviously did love stardom, he liked fame, but he was also interested in diverse subject matter.

LS: Why did you work so closely with the museum in Cologne. Do they have a very special collection of Warhol?

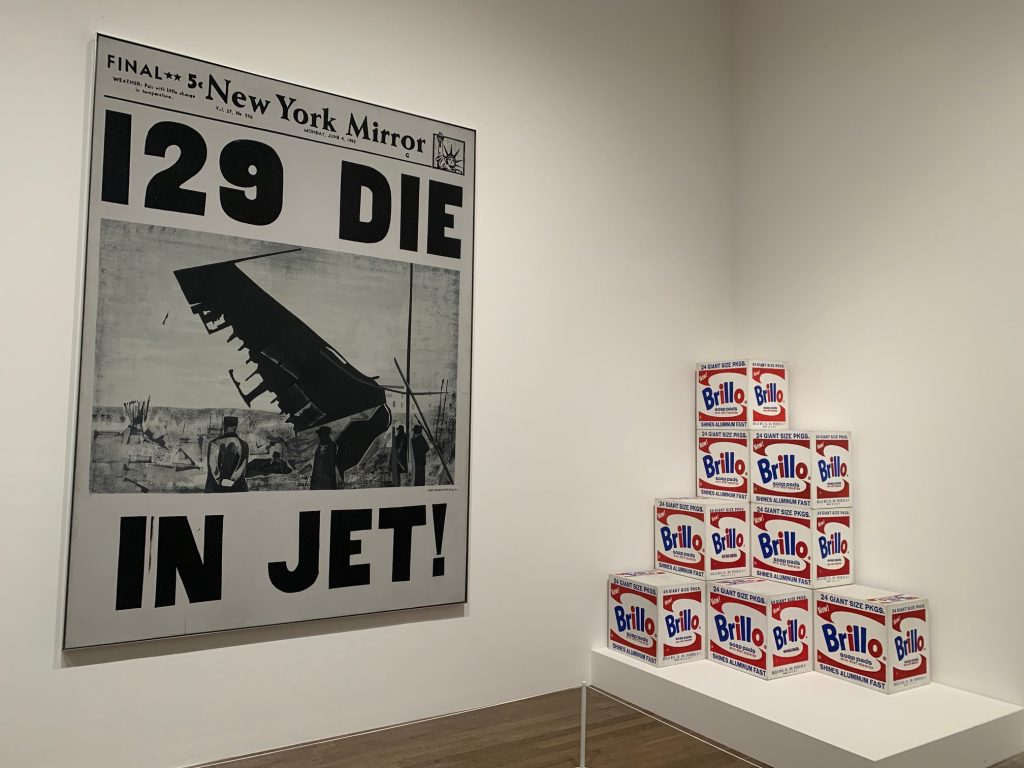

FM: They have a very big collection of Pop Art generally. They were started by 2 collectors. Very often with any exhibition, we collaborate with another venue, so that way more people can see the exhibition. We borrowed three important works from them; the Brillo boxes, the newspaper ‘129 die in Jet’ piece, and the Pink Race Riot, which is quite important for us because it depicts an African-American man being attacked by a police dog in Birmingham Alabama. It was often referred to as Warhol being able to picture not just the consumerism of the 60s era, but also the turmoil and the disasters that took place in the 60s. Because the Sixties started with such optimism, in connection with John F. Kennedy as well, who was seen as this new kind of President. Then when you have the shooting of JFK, and the Jackie series, you see him trying to bring the news imagery into the realm of art.

LS: And you really get a sense of big cultural, pivotal moments, of things that happened in society.

I was really struck by the Brillo boxes. I know they’re very iconic, but I’ve never seen them so up close and didn’t realise how ‘handmade’ they are. Because you always associate Warhol with screen-printing. And also the Coca-Cola bottles and big canvases exhibited near the Brillo boxes. Because you always think of screen-printing. Was he very much more doing things by hand at the beginning with the early Pop pieces, and then later he had other people helping him at The Factory?

FM: He talked about using assistants, he did have assistants, but he was always involved in the making of his works in some capacity. And that’s one of the things we wanted to emphasise, especially with the Pop Art, which people associate with shiny clean new things, but actually they’re very hand made, and you can see the lines where he’s marked up the canvas. Actually I think there’s something about how he uses screen-printing, where he often lets the ink run out, or lets the image become quite distressed, is actually his kind of creative expression, even his mechanical process, his attempt to imbue the mechanical with a kind of human quality. And you see it in other examples, even in the ‘Last Supper’ series, where there’s still some variation in the quality of the print, and in other works in the series he uses different colours. He approaches things from a kind of design perspective, but there’s always his hand involved.

LS: It’s been nearly 20 years since a big Warhol show at the Tate. Why has it been so long? Does it take years to make a show like this?

FM: Yes it takes years to make a show. This took about 4 or 5 years from the moment of deciding to do it to now, and obviously Tate has quite a broad program. We thought this was an interesting moment to think about Warhol because he’s seen to be so familiar, so present, especially in popular culture and not just in the art world. So we thought it would be an interesting time to think about him as a human being, someone who comes from a very particular family, and to actually view his work with a slightly personal touch, even though he himself resisted that kind of association, we wanted to explore how you could look at his work differently though those connections to his family history and his gay identity.

LS: I find it quite ironic that he came from an immigrant family from Eastern Europe, and he became one of the most iconic artists in history and symbol of American culture that I can think of. There’s a real irony in that.

F. Yes, and that was one of the starting points of this exhibition, to think, what is it about this guy who was also very shy, how was he able to capture America, especially in the 60s, even going into the 80s when he was associated with socialising, he was able to force people to take on this persona and accept it. And it was as a strange persona as well. He actively exaggerated his imperfections, his baldness, his mannerisms.

LS: I loved the video installations in the ‘Exploding Plastic Inevitable’ gallery. How did you create that room? Did you have to search in lots of places for the footage?

F:M That comes from the Warhol museum. He showed his films in theatre settings, but he also collaborated with the ‘Velvet Underground’ and projected his films on top of the band. This is an installation that the Warhol museum produced where they tried to replicate something of that spirit of a rock show with these films. So it’s a kind of way for the visitor to feel like they’re in the 60s.

Watch Warhol at Tate on BBC iplayer Museums in Quarantine part 1