Bella Easton

All artists hope to develop a language which is distinctively theirs. That’s likely to take years of experiment and reflection. It needs to feel earned, not just arbitrary. But then, once you have one, how do you keep it fresh? No serious artist wants to be mired in a predictability which means they’re not interested in what they themselves are doing. One way out of that is to use the language to say new things, another is to keep the language fluid by ongoing variation. Either way, something external needs to come in. Katie Pratt, Caroline Jane Harris, Bella Easton and Dillwyn Smith show how that can work – not just the content but the forms of their well-grounded approaches to making work are constantly moved on by chance, time, material and place.

Katie Pratt builds the renewal through chance directly into her method. Her starting point is typically to throw, pour or wash paint onto the canvas in ways that she cannot control to any great extent. She then categorises the marks and seeks order, identifying points of interest to enlarge on, replicate or develop. For example, says Katie, the grooves of brushstrokes may be demarcated in a contrasting colour, or similar flecks linked in a chain. This takes time: years may pass as connections are made through repeated examination of the potential. The result is a movement towards order, towards a solution of sorts, that may sound computational, yet tends to looks organic. And while the paintings are – in essence – depicting their own process, a narrative which the viewer can trace, one might also draw analogies. What of the comparable need to seek political order in the world, to resolve boundaries and adjudicate between competing claims. Either way, considerable variety is generated within a consistent language: here the large Licht’nsteen has a unified oceanic swell, while the smaller Chagging divides its colours and textures more sharply, and Darnington is almost ethereal in its layering.

Where Pratt uses a haphazard manual action, Caroline Jane Harris sets technological processes in unpredictable motion. And where Pratt uses a different starting point each time, Harris often uses one work as the direct generator of the next. She employs all manner of technical processes to expose and explore the digital aspects of such quotidian views as the veiled tree which was the starting point for Afterimage. Caroline laid the digital print over a hand-cut stencil to make horizontal rubbings with white pencil, rendering the absent present in a ghostly work which reads like a palimpsest of screen decay. The tree emerges as the cut-out stencil, at once concealing and revealing its material history. Seeing Vermont I and Seeing Vermont II result from turning two photographs of forests into ‘bitmap’ coded versions of themselves, printed and cut-out by hand from two different weights of paper at the same time. Further layers were added by using the heavy paper-cuts as masks to expose three photo-etching plates using UV light, which were then printed onto the same original photograph. The intricate and visually seductive layering suggests a sense in which, in our current digital surfeit, the world as we see it is somehow hidden behind its digital representation.

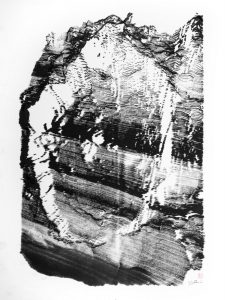

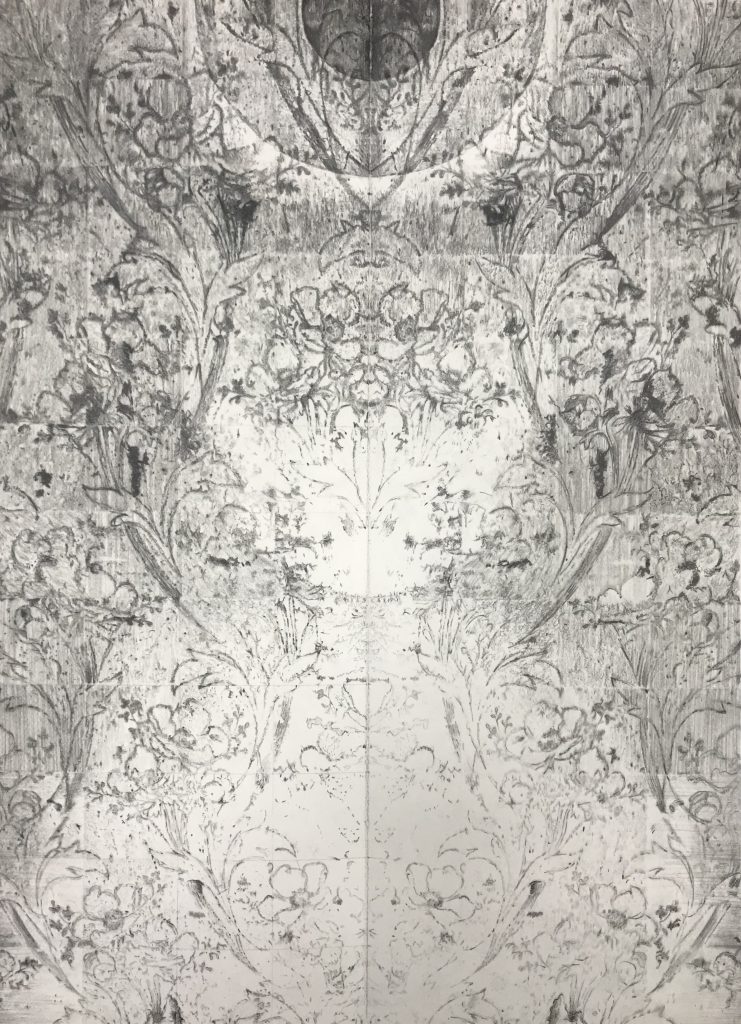

Bella Easton starts with history, and combines the accidental with the generative. Her practice is founded in drawing, typically homing in on domestic details such as the Victorian wallpaper, from which she has made frottage drawings. She recently found a whole section of wall in her house with the ghostly remains of a design that had seeped into the original plaster behind. She has developed, replicated and reflected on that source to generate a complex, intensely gradated, light-filled account of the multiple relationships and contradictions between natural and artificial, open and enclosed, chaotic and orderly, uncanny and familiar. Bella’s method is a hybrid of painting and printmaking: the squares of Bitten By Witch Fever are lithographic prints each pressed onto paper-thin porcelain, in slightly different registrations, around the central axis. The Rorschach-like result is a coming-together that may look like one complete view, but is actually a doubling of two halves. The green colouration refers to the arsenic found in wallpapers from this period: William Morris described the doctors who attributed poisoning to his papers as ‘bitten by witch fever’, wrongly insinuating that they were quacks.

Location is the starting point for the latest developments of Dillwyn Smith’s language, which – like Easton’s – uses material unusually and incorporates very particular sources. He has been cutting and stitching paintings together for some 15 years, in the course of which veiling has emerged as a meditation on the classical painter’s application of glazes. It proves an ideal means of combining and carrying the effects of colour and light which are Smith’s principal interest, setting up conversations with more traditionally-achieved colour field painting and Rothko in particular. Those effects often reflect Dillwyn’s travels: he discovered the Dishdashi cloth at a residency in Oman, and it brings a lightly organic and delicately sensual feeling to the colour washes of the Placebo Paintings, which use the found colours of the cloth without Smith himself employing paint – that is, perhaps, present only in placebo form – and temptingly demonstrate their construction by leaving the wooden supports visible, like legs in stockings. The effect is powerful enough – placebo or not – that it spreads to the pair of nylons Dynamic Duo, which Smith rightly describes as being ‘diaphanous green / diaphanous yellow’.

All four artists, then, have found means of using the externalities of chance, place, time and material to infect their particular languages with new forms. They also share wider sensibilities: all bring transition between time and place into their processes, can be read as referring to landscape and mapping, trammel between outside and inside and are – almost paradoxically – skilled in discovering ‘accidental’ effects. Moreover, the structuring backdrop of the modernist grid, explicitly present in Easton and Harris, is also echoed less obviously in Pratt and Smith. Yet what is fascinating in the end is that the four can share so much, yet remain – in their forms of autonomy – so utterly distinct.

FORMS OF AUTONOMY Katie Pratt, Caroline Jane Harris, Bella Easton and Dillwyn Smith

Curated by Paul Carey-Kent Art Opening: Friday 7th February 2020 6:30pm-8:30pm cc gallery 18 London Road

Forest Hill London SE23 3HF @ccgallery