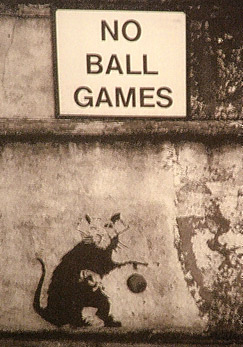

A crisis of ownership and authenticity has erupted over the sale of seven Banksy murals which were removed from the streets of London by a cowboy art dealership called Stealing Banksy? A quick google of the company will turn up one lurid story after another, so here we’re just going to concentrate on the fact that they know nothing about art. The case demonstrates how the market actually serves an honourable purpose in the artworld, as well as teaching us a lesson about the essential nature of street art itself.

The works were sold to private collectors in an online auction organised by Stealing Banksy?, who claim to act as independent agents – independent, that is, of auction houses, city councils, galleries and, of course, Banksy himself.

The company claims it does not sanction, encourage or order the theft of Banksy works or damage to private property. Instead, it acts on the instruction of landlords whose properties have been desecrated/adorned [delete as appropriate] by Banksy in the removal of murals through a process they call ‘sensitive salvage’. Through a painstaking and expensive process, they extract the mural from the wall and reconstitute it elsewhere. They are, then, operating within the great art historical tradition that gave the Prado Goya’s Saturn Devouring One of His Sons, which was cautiously lifted from Goya’s own dining room wall.

In the case of Goya, there is no problem: not only would one reasonably think this meets with Goya’s approval, the works presented to a national collection and they were authenticated in advance. This case, however, is very much muddier because it goes against all the conventions of the artworld and aims to directly offend Banksy himself. Stealing Banksy? is a deliberately vague construct – with its irritating, disingenuous question mark – which wants to give the appearance of cultural altruism: it acts as if it is doing Banksy a favour by further disseminating his work through the channels of the market, thus attaching to it that peculiar kudos of a cultural product which not only has value in and of itself, but has – suddenly and miraculously – the mobility which enables art to be seen the world over.

This appearance is a mere conceit which hides the fact that the company exists purely for the promotion of private interests, which is a mortal insult to public art. Stealing Banksy? acts in the interests of landlords who never asked for their walls to become artworks, who suffer from the continued attention the works draw and who face potential losses to their businesses if their buildings are given grade II listing status. Furthermore, they sell the works to private collectors in a manner which is just short of clandestine – through online auctions after entry fee charging exhibitions in hotels – thus bypassing all the ordinary, well-established conventions of the art market.

Whatever Stealing Banksy? is about, it is certainly not about art. In its paltry defence, it says that it does not make any money from its ventures, as if we are so air-headed that this news instantly anesthetises us to forget the serious issues here. One also wonders, then, why they bother serving the landlords and collectors at all if they don’t make any money, for even the most culturally and intellectually adept dealership still wants to turn a profit. The only explanation can be that Stealing Banksy? thinks it is performing a public service, giving its activities the air of pompous moralising.

There are two serious issues here. Firstly, there is the issue of who owns the Banksy work and who therefore has the right to remove or sell it. It is too simplistic to say that the landlords are the rightful owners since they are painted on the sides of their buildings, given that they do not take this attitude towards any old piece of graffiti. The thing that strikes terror in the dark heart of capitalism is that street art – in its pure and original form – transcends private property: it uses the inert physicality of private property as a means to the end of creating truly public works of art; the point is much less about those individual rights that Locke promised than it is about making art divested of the notion of ownership. If a Banksy belongs to anyone, it belongs to everyone, and it can only be removed through some gruelling democratic process which is directed towards the public good.

The other issue concerns authenticity. Banksy has set up Pest Control, which authenticates prints and paintings attributed to him, but does not authenticate murals, which are generally supposed to be by Banksy. As such, Stealing Banksy? has no mechanism by which it can guarantee buyers that they are purchasing a genuine Bansky – in the world of fine art sales, even a universally held supposition is no replacement for a certificate of authenticity supplied by the artist.

This reckless, idiotic practice of Stealing Banksy? means that, in real terms, anything you buy from these people is utterly worthless, both culturally and economically.

The case of Stealing Banksy? has a sobering lesson: although it seems like a good idea to take a leaf out of Banksy’s book by operating covertly outside of the artworld, it is doomed to failure. So long as you are dealing with art, you need the infrastructure of the artworld in order to function, since it is here that authenticity, dissemination and criticism are administered through the conventional framework of the global artworld. The market, no matter how reviled, is a crucial part of the artworld: its not just about making rich people richer, its about controlling the flow f art in a way that preserves authenticity and integrity of the work.

By flouting these conventions, Stealing Banksy? is not doing something revolutionary or refreshing; it is causing serious harm to Banksy and to art. Whilst, perhaps, they are laughing all the way to the bank, let us remember that, as Rev Flowers has recently taught us, he who laughs all the way to the bank eventually also laughs all the way to Hell.

Words: Daniel Barnes