Painting is a medium bound to history, to sources, to genre and to the tensions that exist between figuration and abstraction. What it is to paint in the 21st century, to apply substance, colour, mark and line to a surface is complicated by our relationship to art as a critical practice, and histories that from the late nineteenth century avant-garde to the present, have turned the practice of painting upside down and inside out: strategies include the blurring of painting and performance, video, or objects and installation. The surfaces that can be painted are exploded, compressed, deliberately and strategically vandalised. We continue to grapple with the conversations and arguments that exist between figuration and abstraction.

In this recent body of work by Henny Acloque (b.1979) the self-reflexive relationship to painting – its sources, its histories and its relationship to genre – is present but not overly determined or explained. These are not violent disruptive works: they are rather quietly reflective while conscious of the tensions attached to the processes of thinking about painting in the 21st century: ‘If one doesn’t struggle with painting now then what’s the point of doing it. You’ve got to fight with it. There is always a struggle in my work with old and new’. There is integrity to the work: this emerges from Acloque’s particular relationship to paint, and to the images and worlds that preoccupy her everyday life, and her travels to other times and places. She restores the painting we call Old Master Paintings alongside her work as an artist, and speaks of influences that range from family or personal collections of books and objects to travelling to Mexico.

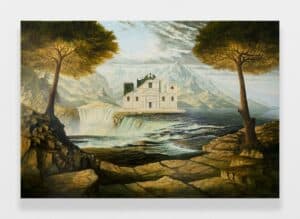

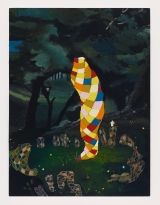

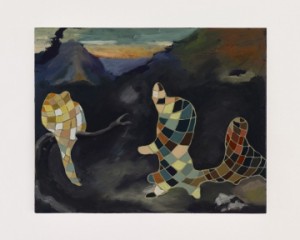

At once seductive and beautiful, Acloque’s paintings are also unsettling. We recognise the landscapes. We’ve seen them before. They are embedded in our cultural imaginary, no matter where we come from geographically. They are the landscapes of European painting, and illustration: Landscapes that have travelled and migrated, not only in collections, both public and private, but also in books and catalogues, and in the paintings of colonial traveller-artists. At the same time, as we try to trace their sources and their origins we cannot: the places they invoke or represent are unattainable and unknowable. In this we realise our own displacement, and the elusive search for a ground. Acloque tells us that a source was a Victorian book of fairy paintings, inherited from her father, landscapes that take their imaginary status for granted, as we (looking at them) seek refuge in the magical, ‘anything is possible’, worlds they offer us.

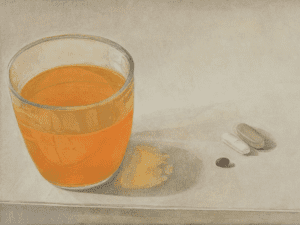

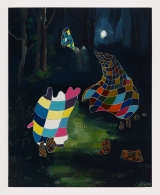

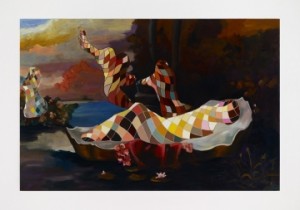

Forms suggest human figures shrouded in Acloque’s abstracted and colourful patterning. The figures are humorous and playful, as they are uncanny and unsettling. We recognise the human form as distinguishing features and characteristics are hidden from us. In works such as ‘Am I Not Merciful’, Acloque’s figures resemble the dead, wrapped for burial, although standing rather than immobile and lifeless. In ‘Come’ we are reminded of the forms and conventions of narrative painting, and the female bodies, that placid or animated, populate the continuous impetus to cast and re-cast the ways in which myths, legends and historical events are narrated. Acloque’s painting speaks to us of time and its passing (an established part of the history of painting from Vanitas to Memento mori). Her paintings suggest a philosophical understanding of time that in memory (both cultural and personal), is amorphous and inherently ungraspable. Perhaps because of its particular relationship to History, painting is a medium particularly bound to time, to the human condition, and to history’s continuous looping: backwards, forwards and backwards again. ‘With these paintings you’re not quite sure what time it is in terms of epoch. I play with that. The figures have no historical time-reference. I play with time, and don’t set it in stone at some particular point. I was thinking of practices I encountered in Latin America, the transportation of minds to new worlds whether to the past (to ancestors) or to the future (trying to make predictions). I look at these paintings as expeditions of the mind but you’re not sure whether they’re from the past or the future.’

Review by Yvette Greslé

Henny Acloque ‘Life after magic’ at Ceri Hand www.cerihand.co.uk

Through to 11th May 2013