Street art is big business. Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled (Yellow Tar and Feathers) (1982) sold last November at Sotheby’s New York for $25,925,000. The phenomenon of Basquiat’s prices and the more general taste for street art of which it is symptomatic is a product of the art market’s ability to disseminate otherwise obscure art and to launch it into the establishment. It’s as if the market bought into social disaffection, cleaned it up and sold it back to the very establishment which it was meant to critique. Although we might think of this as selling out, it is important to recognise that without the injection of money in the 80s today’s street art would be impoverished.

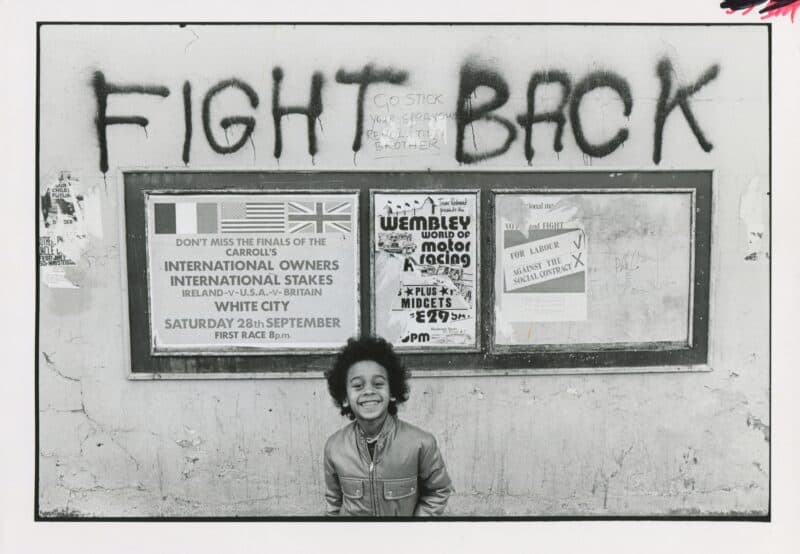

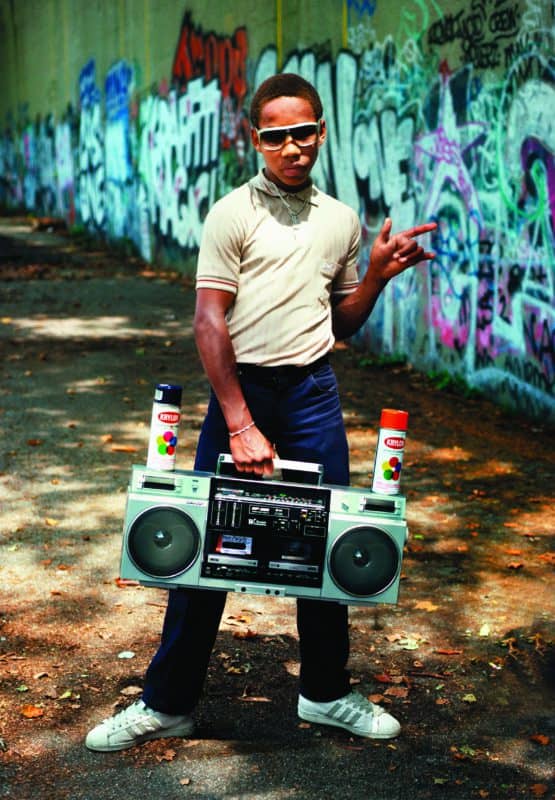

It was in New York City that street art as we now know it flourished at the hands of young, eloquently disaffected artists. Warhol laid the ground, although he was relatively quiet during the 1970s, making those brilliantly timed portraits of the Shah of Iran and of Mao. He had entangled art with commerce, consumerism and celebrity, initiated mass-production, showed that everywhere there is art and everywhere there is money to be made. He had also established The Factory as a meeting place, where he would seek out the next generation of artists. Warhol opened up the field for young artists, providing new ideas of how to practice art and what it could be about, regenerating the possibility of art’s power to both critique and celebrate contemporary life through politics and popular culture.

The young Basquiat emerged in a New York City that was seduced by this possibility. He started tagging as SAMO in 1976 and by 1979 had had more than his fifteen minutes of fame on cable TV. He wanted to expose difficult social dichotomies of poverty and wealth, integration and segregation. Through graffiti he appropriated poetry, merged image and text, walked a line between abstraction and figuration, and combined historical reanalysis with cutting contemporary critique; he was art historically entrenched, but he was doing something new. Basquiat posed questions with such emotional intelligence, historical awareness and artistic finesse that works like Irony of a Negro Policeman (1981) seduced the establishment pretty quickly, and soon he was collaborating with Warhol on those delicious Olympic Ring paintings.

Basquiat’s success was partly due to his fearlessness and his relationship with Warhol, but there was something else in the air. The market was booming, neo-expressionism was becoming popular, but after the heat of the exuberant 60s and 70s the air was beginning to chill. In the 80s, a spectre was haunting America, with Reagan and AIDS threatening catastrophe, so Basquiat’s mobilisation of art in calling for change captured the zeitgeist. Having started out on the street as a renegade, Basquiat was suddenly showing inside the galleries and making work on canvas. Not only was the work strong, but the timing was right for the art establishment to latch on to this energetic, political and highly sellable art. Nowadays we call that selling out, but in those days it was called success, especially for an African-American with such a stark re-examination of black history and critique of contemporary social conditions.

As the gallery and the market began to take note, Basquiat hailed a new wave of the artistic and political outsider being brought inside. Just as a black kid from the Lower East Side made good, a gay white kid, Keith Haring, began to paint his trademark Radiant Baby on the NYC subway. He was soon travelling the world, eventually winning a major commission from the National Gallery of Victoria, Australia and leaving a monumental work in Pisa, Italy. His commercial success, as well as his mission to break down the barriers between high and low art, was bolstered by selling handmade merchandise in his Pop Shop, which traded until 2005.

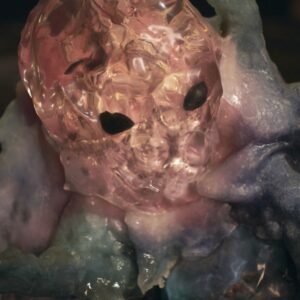

But Haring’s message was darker than Basquiat’s: it was about male sexuality, the spiralling AIDS crises and America’s crack-cocaine epidemic. In particular, Haring’s work unpacked his thorny attitude towards homosexuality, which was stricken with fear, threat and guilt; imagery of monsters, skeletons and beasts betrayed his terror and inherited sense of perversion. He was morbidly obsessed with the inevitability of his own AIDS diagnosis even before it happened, and represented it in his work with a malicious horned sperm that plagued a man who was burdened by carrying an egg (eg Untitled, 1988). Expressing a progressive politics and dragging the subculture to the mainstream, topped with a prime spot in the Warhol/Basquiat moment, assured Haring’s artistic and commercial success.

Haring and Basquiat were audacious to addresses such incendiary social issues, but the art was strong and the market congenial, giving a new voice to the street. Money and fame followed, but their major contribution is not just in the acceptance of street art, but in the politicisation of contemporary art. This has been particularly profitable for Barry McGee, who found himself on a fast track to success with a practice that views the city as a site for activism, resulting in a show at the 2001 Venice Biennale, where his prices predictably soared. McGee straddles the street and the gallery, exploring the duality of art and graffiti, enacting a critique of contemporary American life.

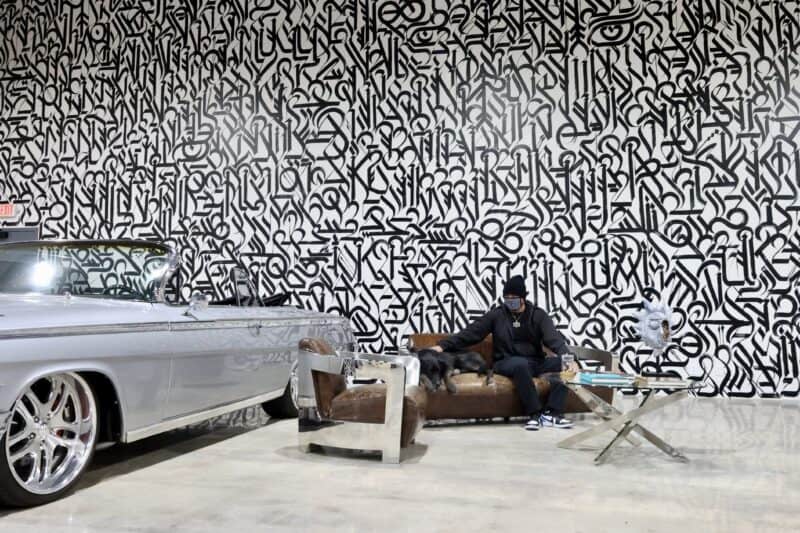

In this move from street to gallery, the aesthetic has changed. Dan Colen makes text paintings in which the text is painstakingly rendered with a brush to look like spray-paint and the surface is carefully prepared to shimmer in contrast to the scrawling text. Similarly, RETNA has that trademark script, descended from Egyptian hieroglyphics and Native American symbolism, which often does not look like writing at all, but pulsates on the canvas in glistening colours. Whilst this is part of the natural evolution of traditional street art motifs, it is undoubtedly also a response to a market which covets a recession-defying bling aesthetic.

The New York artists saw art as biting critique in the bemused gaze of a waiting public, which set the standard for street artists internationally. But for its part the market not only funds the artists’ work and lavishes all the glorious trappings of the establishment, it also acts as propaganda minister. By co-opting the mass media’s obsession with astronomical prices, the market helps promote the practices of artists who are otherwise toiling away in a small corner of a big world.

Words: Daniel Barnes