There’s never a great time to be skint, but when Berlin’s historic contemporary art institute KW commenced ground floor renovations late last fall — a long awaited (re)reshuffling of its entrance foyer to comply with fire regulations and led by newly appointed director Emma Enderby — the city’s decision, just days before Christmas, to drastically slash cultural funding to the tune of €130 million couldn’t have come at a less opportune moment.

After several months of partial closure the listed building reopened last week with a brand new entrance — except despite its fresh face, there’s not much that’s actually new about it. Having salvaged from its own material archive, newly installed fixtures are steeped in history. From paper to plaster, the legacy of exhibitions past is repeatedly embedded into the fabric of the space.

Facing a 14% funding cut, not to mention a near 40% increase in German construction costs since 2020, the renovation project was executed completely in-house with nary a starchitect in sight. Working with the internal tech team to reuse as much pre-existing infrastructure as possible, the revamp has also gained 15m2 of reception space: embodying a uniquely Berlin-style survival strategy whereby resourcefulness is a way of life.

The entrance — formerly a quirky side door in the far right corner — is now located front and centre, opening onto an ingress that improves barrier-free access and optimises flow directly to the ground floor exhibition. It is also the original placement, which was first moved by former Director Krist Gruijthuijsen in 2016. Relocated and expanded storage lockers feel same but different, freeing up the former entrance for art mediation as well as carving out space to house offices for the upcoming Berlin Biennale.

As one room unfolds onto the next, each space features carefully considered details that draw on preexisting artworks, all of which have been integrated over decades into the façade, landscape, and interior architecture of the building. In fact by the time one reaches the entrance, the visitor will have encountered numerous commissioned artworks. It’s these commissions that have been used as inspiration to animate subliminal design choices in the upgrade.

Arriving at KW is a process. Behind an unassuming set of double-doors — one painted blue, the other black; an artwork in themselves by Philippe Van Snick — the visitor emerges onto a courtyard. In the far left corner, Stepping Stairs, a mural by Berlin-based artist Judith Hopf spans the height of the west wing; a section of the building housing an internal stairwell leading between exhibition floors.

Formerly a kind of back stair, the new layout has now designated it the main staircase. This in turn centralises a handful of small bathrooms situated in between the landings whose natural accumulation of wall scribbles and decals read like their own sticker archaeology: years of Berlin art and cultural legacy in the form of undisturbed toilet art.

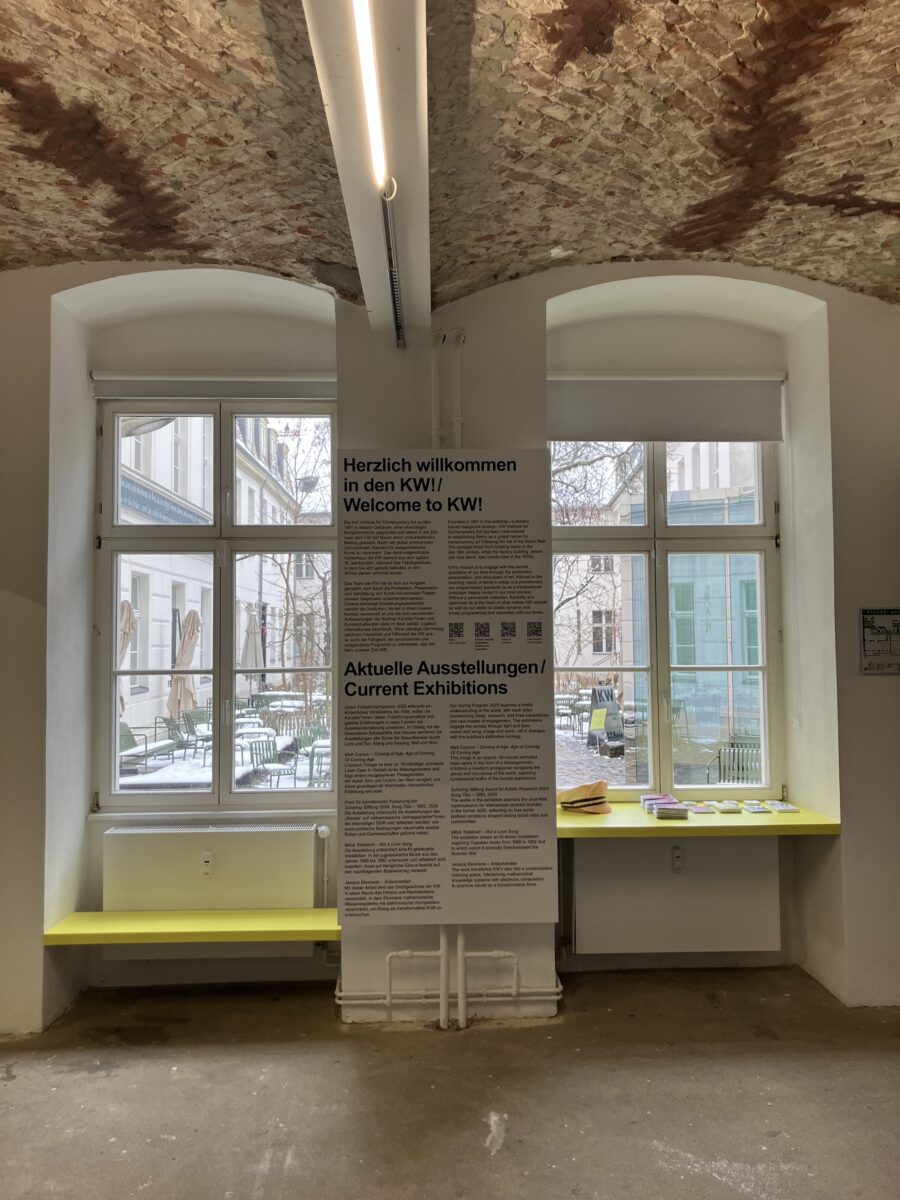

Painted in 2018, the mural’s lemony yellow hue has been colour-matched, now popping up on numerous surfaces, from the reception desk to the shop shelves, windowsills, and even exhibition flyers. The reception room is anchored by a squiggly white bench repurposed from Luiz Roque’s 2024 exhibition Estufa, which concluded just before the renovation.

Subtle references continue throughout the space, including an interior fenestration feature above the ticket desk. Bespoke wall cut-outs facilitate circulation, add visual intrigue, and mirror Olaf Menzel’s Tegeler Web, a concrete artwork produced for KW’s 2005 exhibition Regarding Terror: The RAF-Exhibition that has since become a permanent fixture in the building.

Situated in a disused margarine factory turned 90s arthouse, KW stands for Kunst Werke (Art Works), a name that references not only the art inside but a space of production. Non-profit since day one, the institution evolved from a 1991 initiative of founder Klaus Biesenbach, and spent its first decade on the brink of financial ruin.

After initial renovations of the building exceeded the budget by almost one million Deutschmarks, KW found itself seriously in debt just five years in. Owing to architects and construction companies, a well-timed injection of lottery funding in 2000 helped to evade bankruptcy, after which a more refined funding strategy evolved. Today, support comes through strategic partnerships, public funding, and a patron body.

The DIY-style turnover of the space illustrates an industrious spirit of bottom-up development. The enterprising problem-solving is there, but not at the expense of curatorial sensibility. What’s most inspiring about the quick reno, perhaps even more than making it work on a budget, is the sustainability factor. As cultural funding continues to look grim, perhaps more museums should take a page out of this book and normalise the reuse of materials already available to them.

A lot of Berliners are tired of the old saying poor but sexy — an incantation coined by the city’s former mayor alluding to the pervasively dire financial state of affairs — but I say, if the shoestring fits…