The theme of this third season of Value and Ideas is the meaning of art. The value of art is, after all, partly concentrated on what it means to us at a particular moment in our lives, how we interpret it, and what it tells us about the world we live in.

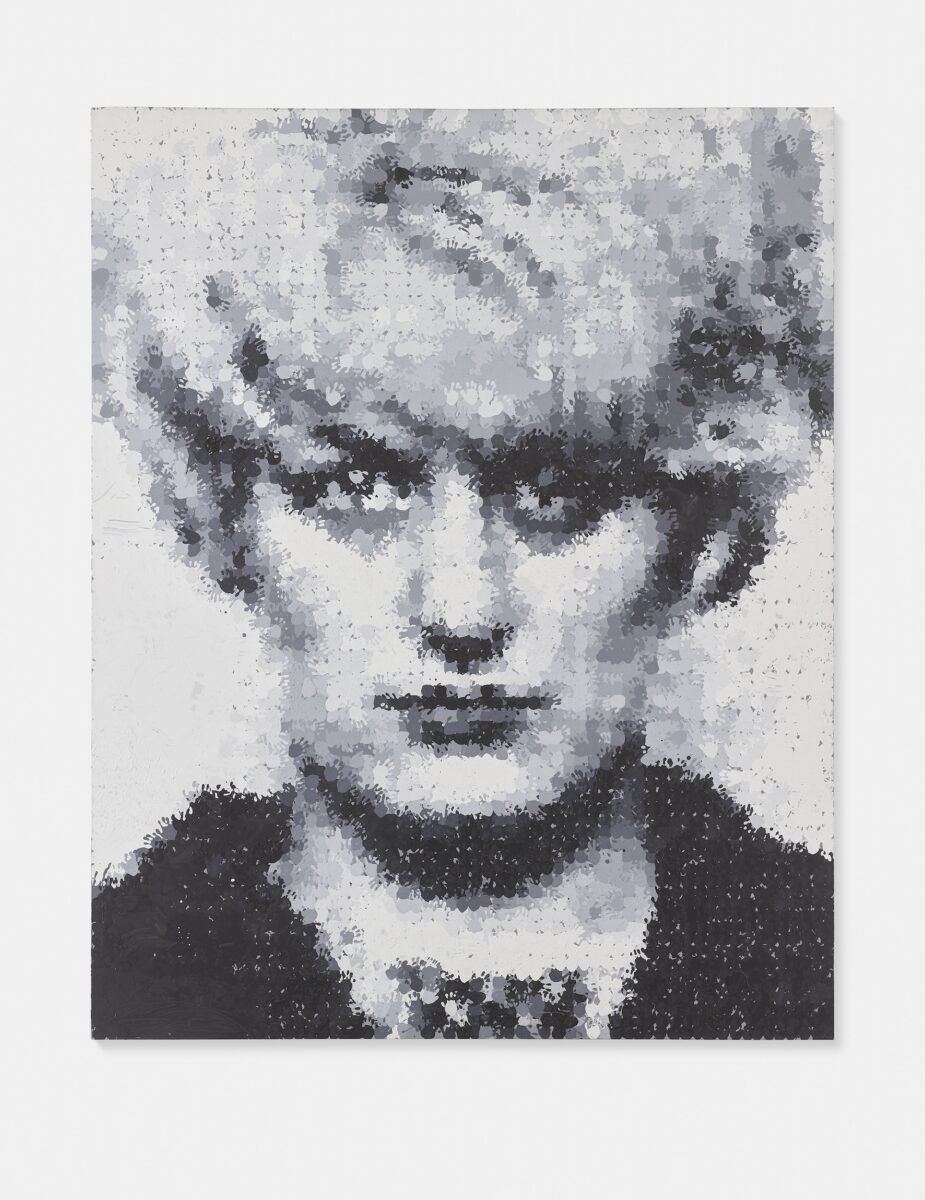

On the first day of the ‘Sensation’ exhibition, Marcus Harvey’s Myra (1995) was attacked twice: first with eggs, second with ink. Legend has it that, following the ink-splattering, the bigwigs at the Royal Academy made an urgent call to Harvey’s studio, suggesting a plethora of magical, expensive and complex resolutions. Unperturbed, Harvey asked for the painting to be returned, whereupon he laid it on the floor and scrubbed it clean with a scouring pad and some Ajax.

There is much in this story that is simply unbelievable today. In 1997, images and words exerted a particular power in a world dominated by print media, television and radio, before social media and culture wars, even before Big Brother. Nearly thirty years later, we have such a proliferation of content through social media that it’s difficult to imagine a single image, especially one by a contemporary artist, inspiring a tsunami of reactions across continents and times. The reactions to Myra, unlike the loud and vain viral phenomena of social media, were broad and deep on a distinctly 20th-century scale: made exactly thirty years after Hindley’s arrest, the painting sparked anger every time it was displayed.

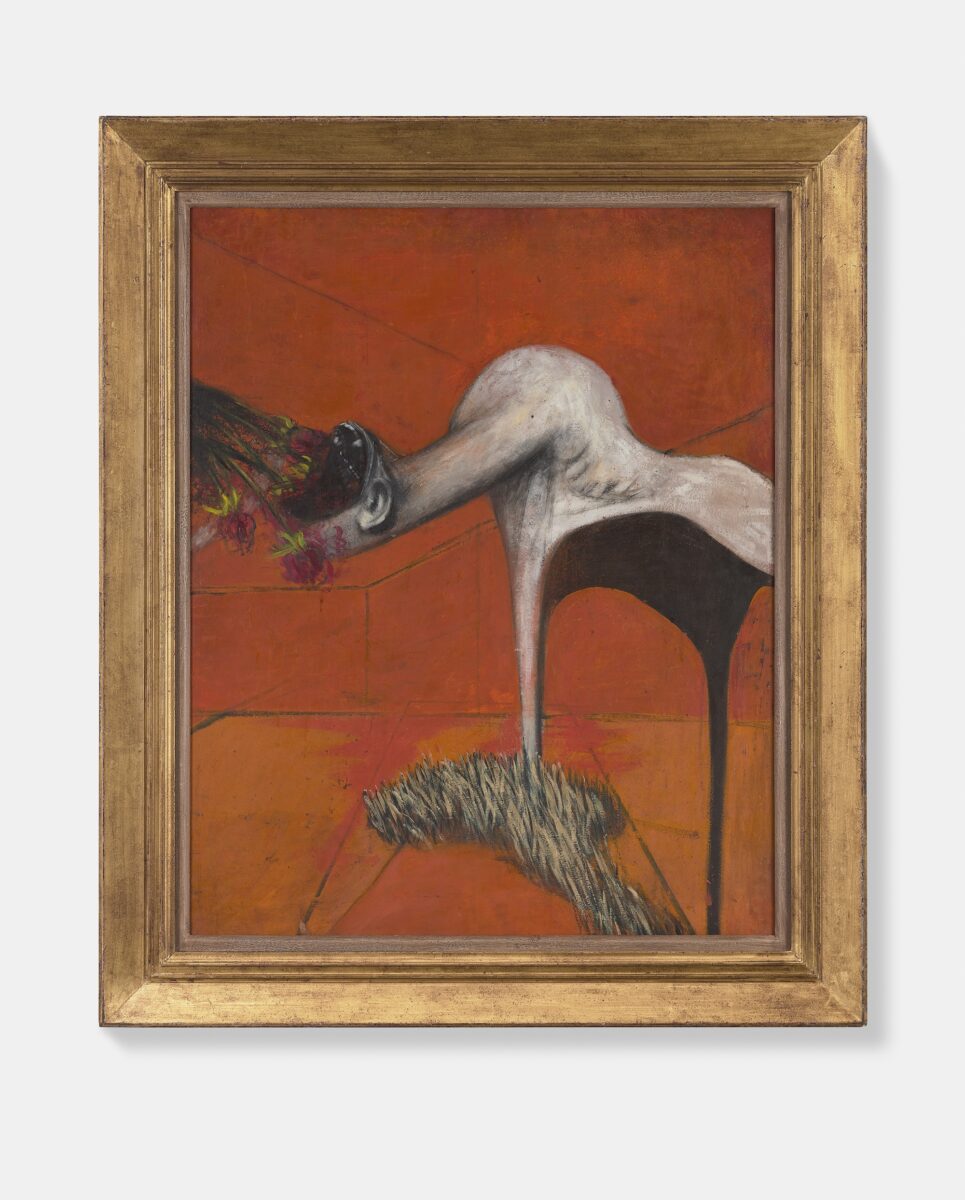

Myra is currently on display at Damien Hirst’s Newport Street Gallery, in an expansive show, ‘Dominion’, curated from the family collection by nepo-baby, Connor Hirst. Amongst works by Jeff Koons, Sarah Lucas, Andy Warhol, Rachel Howard and Banksy, Harvey’s seminal work is among the biggest, dwarfed only in physical stature by a captivating Spot Painting and in grandeur by a remarkable Francis Bacon.

Now a generation old, Harvey’s masterwork doesn’t disappoint: based on the iconic mugshot in which Hindley appears both excruciatingly composed and brimming with menace, she glares down at you, drawing you into her orbit and gradually pixilating as you lose yourself deeper within the painting’s folds as it mangles and chews up the entire room. Harvey’s stroke of genius was to both faithfully copy the mugshot, making a popular culture icon of practically the only image of Hindley anybody has ever known, while simultaneously adding the conceit of its allegedly being composed of children’s handprints from a plaster cast. It works on so many levels and has lost none of its vivacity today.

It does, however, seem to have lost the ability to shock and outrage. Prior to the show’s opening, the display of Myra was reported in The Guardian and The Art Newspaper but barely a whisper since. No eggs, no ink, no Ajax needed. Hindley’s crimes are no less despicable now than before, but the silence is more a symptom of the fact that we are inundated with provocative images, so every provocation is but a blip on the way to the next one. Perhaps short of desensitised, we are inured to mere images, even of serial child killers.

Although the art of the 1990s may have lost its shock value, there is an indivisible remainder. Contemporary art now is safe; it no longer takes risks or concerns itself with bold statements, almost as if it has devolved that responsibility to social media. But here at Newport Street Gallery, you are bombarded with coarse, crass, cryptic and critical artworks that still feel vital, born as they were from a deep desire to make art matter. I know what you’ll say about the YBAs and how you’ll scrabble to defend art’s current ideological posturing, but nothing today gives the same feeling as Myra.

Even when you subtract the shock value, Harvey’s Myra, along with Lucas’ Bunny sculptures, Hirst’s sharks, the Chapmans’ Goyas, Turk’s rubbish bags and Emin’s quilts, exude courage as they cross uncrossable lines. The art of ‘Sensation’, much of which Hirst now owns, remains equally chilling and tantalising in ways that so much contemporary art, focused on safe themes and meeting expectations of decency, simply fails to achieve. Seeing Myra now shouldn’t make us want to return to 1997, even with a general election on the horizon, but it should signal to the artworld that style is as important as substance.

DOMINION, Newport Street Gallery, London, 24th May – 1st September 2024.