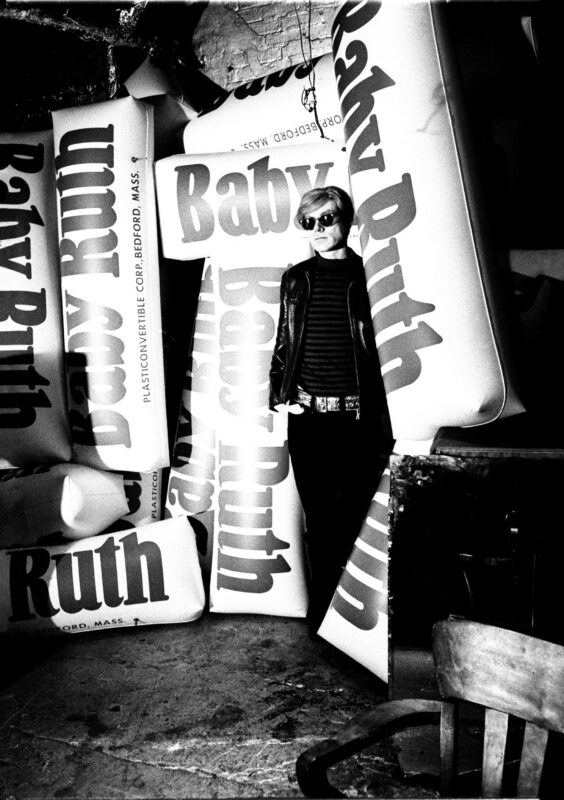

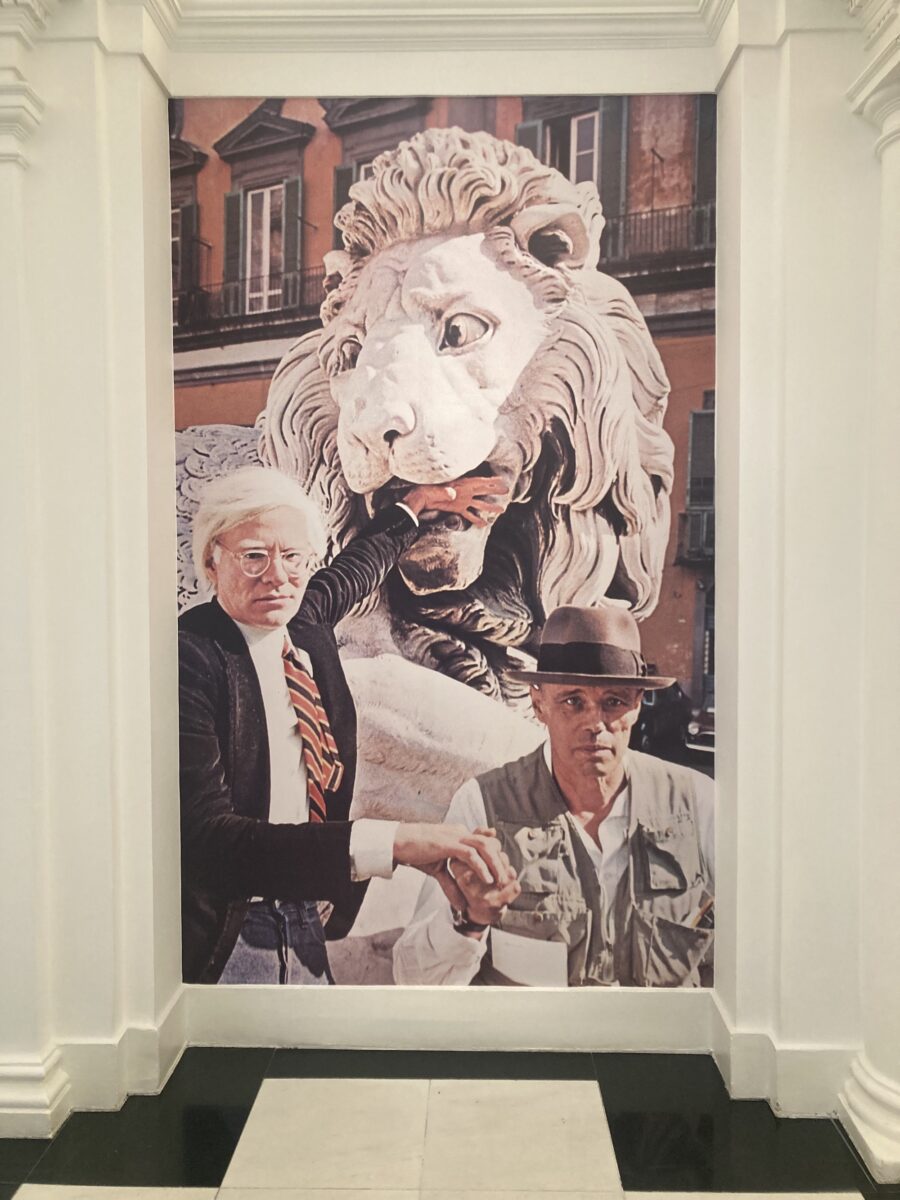

The first and most charged picture met by the visitor in Thaddaes Ropac’s current exhibition, The Joseph Beuys Portraits —a series of screen prints and drawings depicting the iconic sculptor and social activist from the late career body of work by Andy Warhol — is a photograph of the two artists that is plastered over an entire wall at the entrance of the gallery.

In the photo, the two stand at the sun-washed Piazza Dei Martiri [Square of Martyrs] in Naples in front of a large statue of a lion, each sporting their highly recognisable uniforms; Beuys in his characteristic felt hat and fishing vest, Warhol in his formidable suit, neat bowler cut, and thick-brimmed glasses. The year is 1980, April. They are in Italy, and they are both tourists. If Warhol were alive today, we would no doubt label him a hipster; his tie is arguably ugly, but in an ironic kind of way that makes it cool. What’s curious, comical, and even slightly campy about the photo is their pose; they aren’t holding hands so much as Beuys clutches the hand of Warhol and Warhol allows his hand to rest softly in the palm of Beuys’.

It looks like something out of an awkward cotillion dance. Warhol’s other hand is draped delicately in the lion’s mouth, suggesting an unexpectedly whimsical narrative of triangulation between the diva, the utilitarian, and the cat. Warhol stands above Beuys; dominant, but also like a distressed damsel in an ivory tower. The picture was actually a poster for a joint exhibition at the nearby Lucio Amelio Gallery, taken on the occasion of the opening. The exhibition exhibited the first series of portraits, a number of which are currently on view at Ropac.

Headlining the exhibition text is a quote which has been published somewhat ad nauseam.

For those who witnessed them approaching each other across the polished granite floor, the moment had all the ceremonial aura of two rival popes meeting in Avignon.

— David Galloway, 1988

Written by American journalist David Galloway describing the first encounter between the two, which happened nearly one year prior at an art opening in Dusseldorf hosted by the critic Hans Mayer, Galloway recalls the two artists “approaching each other across the polished granite floor” like some kind of divine confluence. The way the quote is written and excessively republished, one almost imagines the seas parting to facilitate this holy moment.

The encounter was thankfully also filmed. It is in this footage that one can clearly see that they did not, in fact, approach one another. Rather, Beuys makes a beeline for Warhol, pursuing him with a blunt and wholesome certainty that beautifully encapsulates prototypical German sensibilities. Warhol stands still in a crowded corner, surrounded by his entourage, posing with the aloof ambivalence and vague friendliness exemplary of American charisma. They meet, they greet, and Warhol snaps a quick polaroid.

Despite only just meeting face to face, the encounter was prefaced by a collaboration in 1978 when Warhol created a campaign poster in support of Beuys’ Green Party. In addition to making comments alluding to the fact that Beuys would make an excellent United States president, the seafoam-coloured poster proliferated Warhol’s international recognition and particularly his popularity in Germany as well as the rest of Europe. Signed by Warhol, who was otherwise not politically minded in the least, the poster functions more as an artwork, a homage, or even just a joke rather than actual political propaganda.

The polaroid and subsequent factory photo as well as its grossly romanticised interpretation, set the stage for the enigmatic and somewhat cultish obsession with the coming together of these two postmodern “prophets,” both of whose legacies have been celebrated to unprecedented proportions. In actuality, the continued coming together of the pair, transcendent as it may have been for some, was a calculated and curated manoeuvre. After that initial rendezvous at the opening, German art dealer Heiner Bastian, a dedicated patron of both artists, persuaded Warhol to invite Beuys to the factory for a reunion, during which the photo from the collection of portraits was created. To say that Beuys and Warhol were friends, as news outlets often seem to do — even unlikely ones — is something of an overstatement.

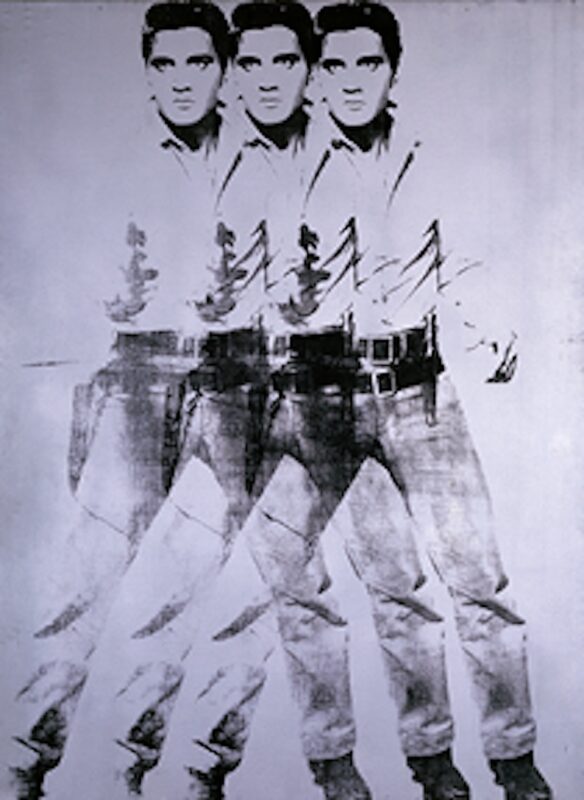

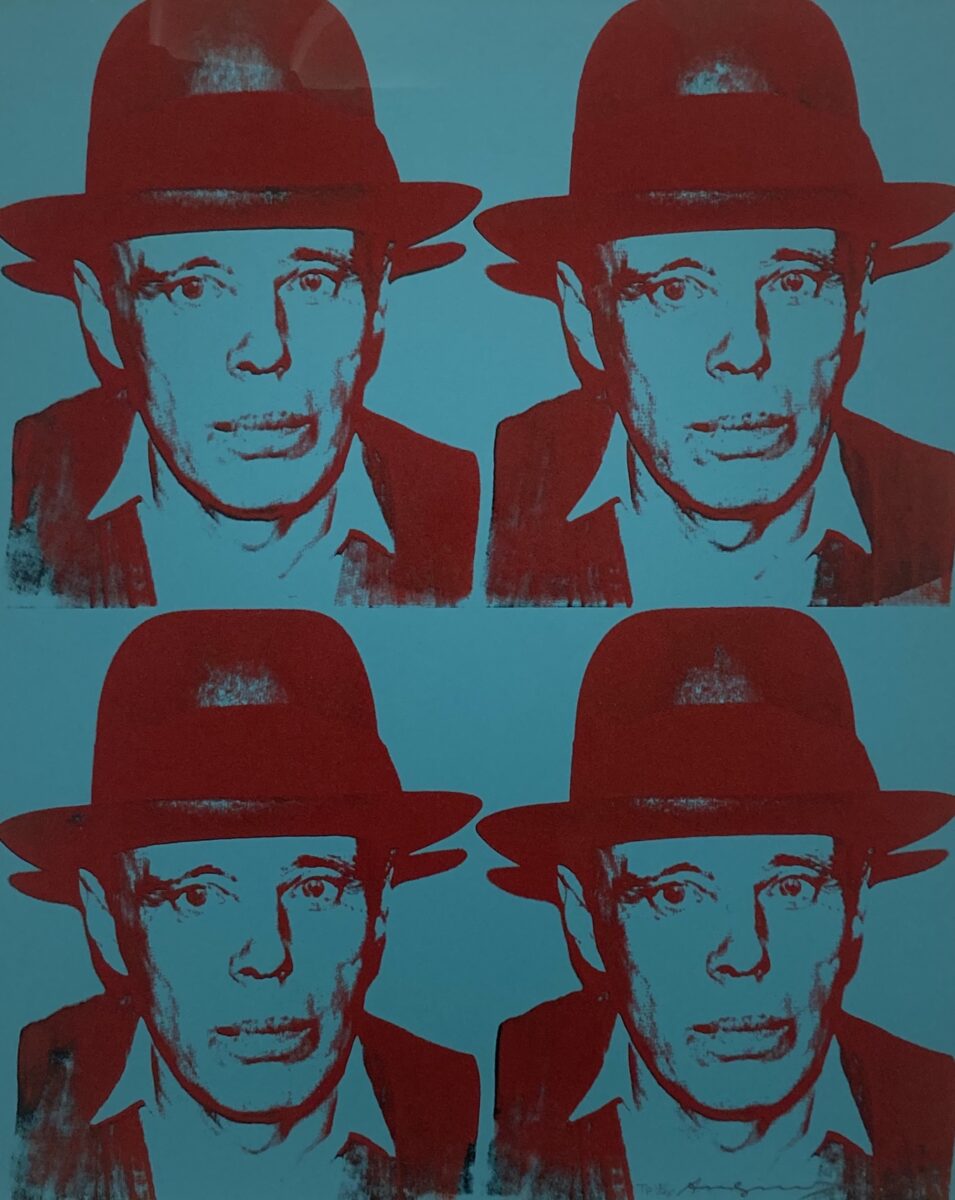

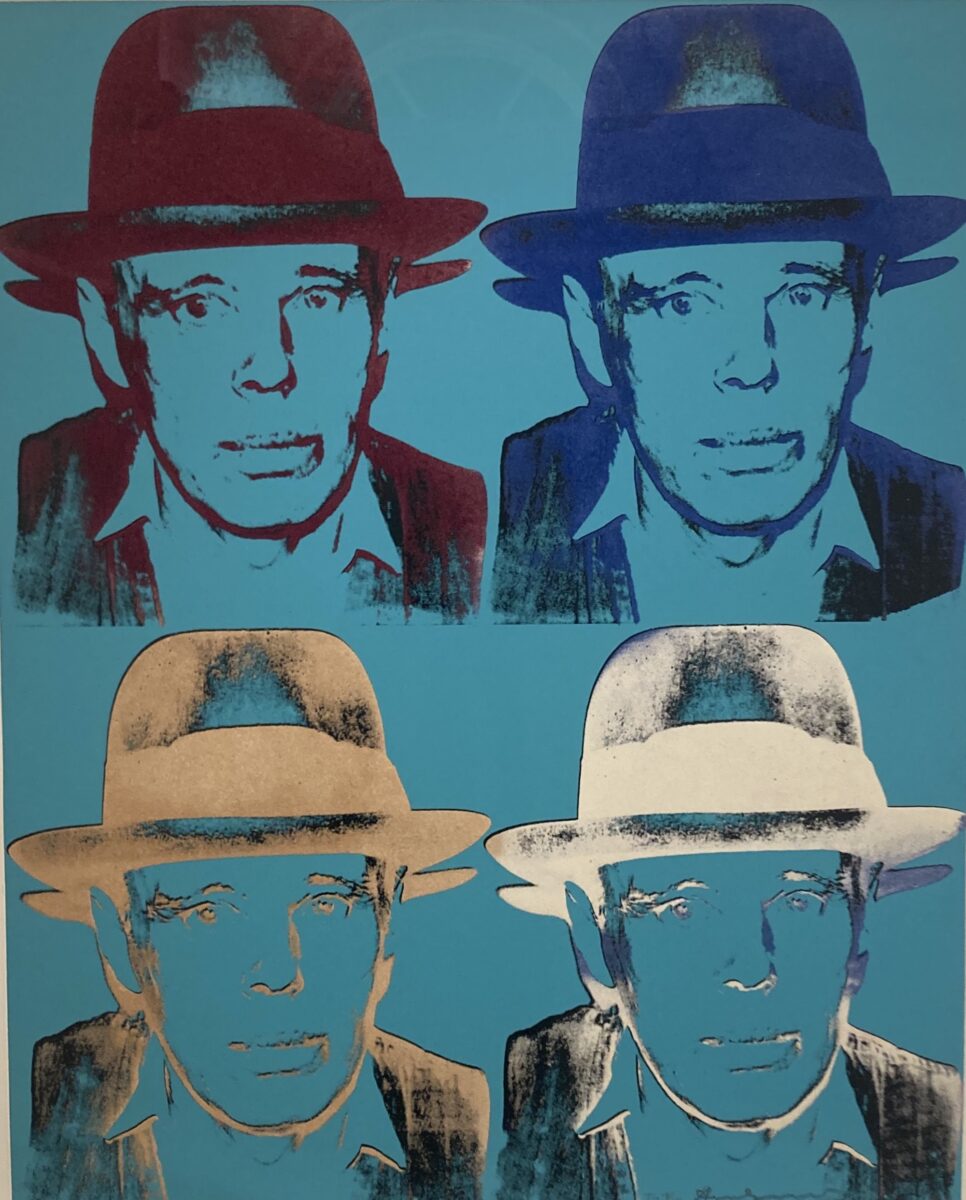

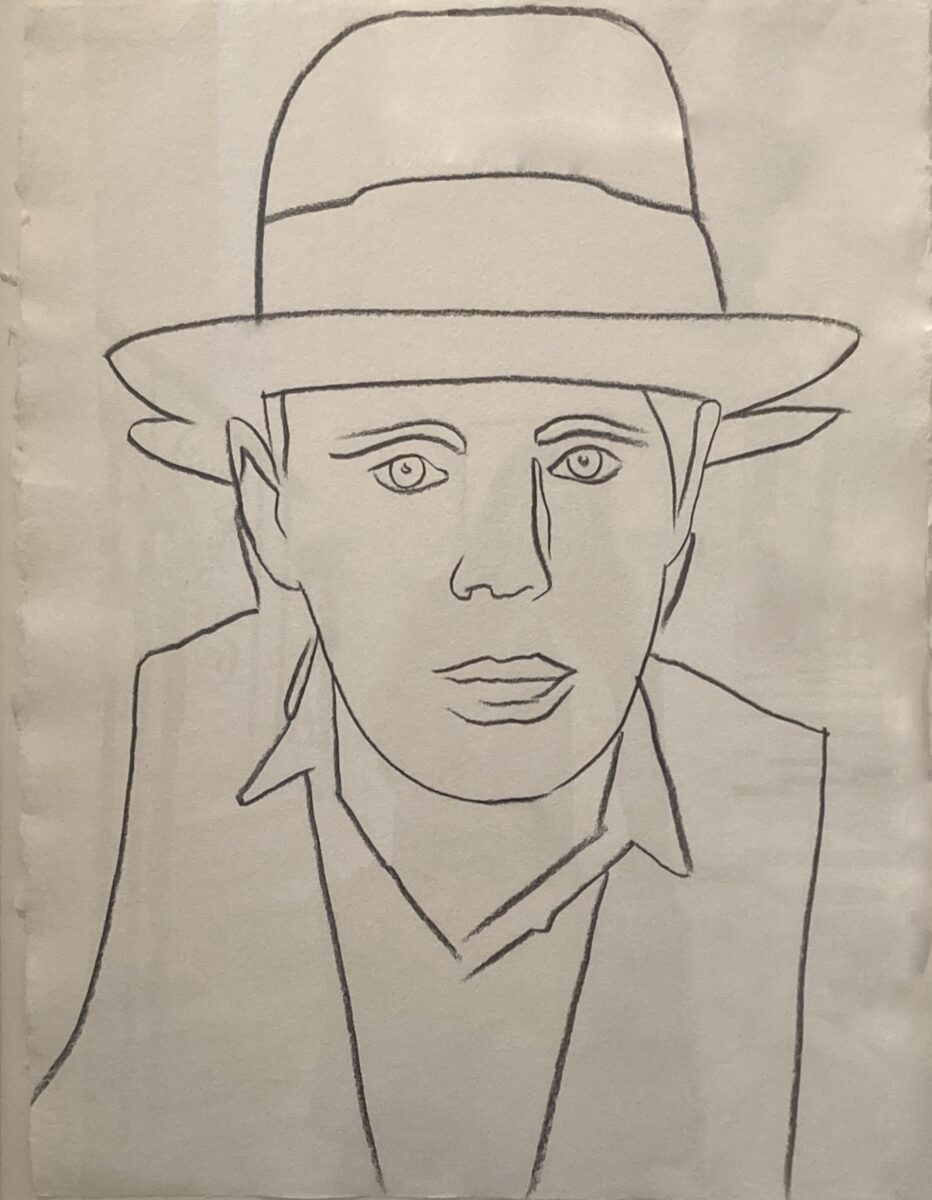

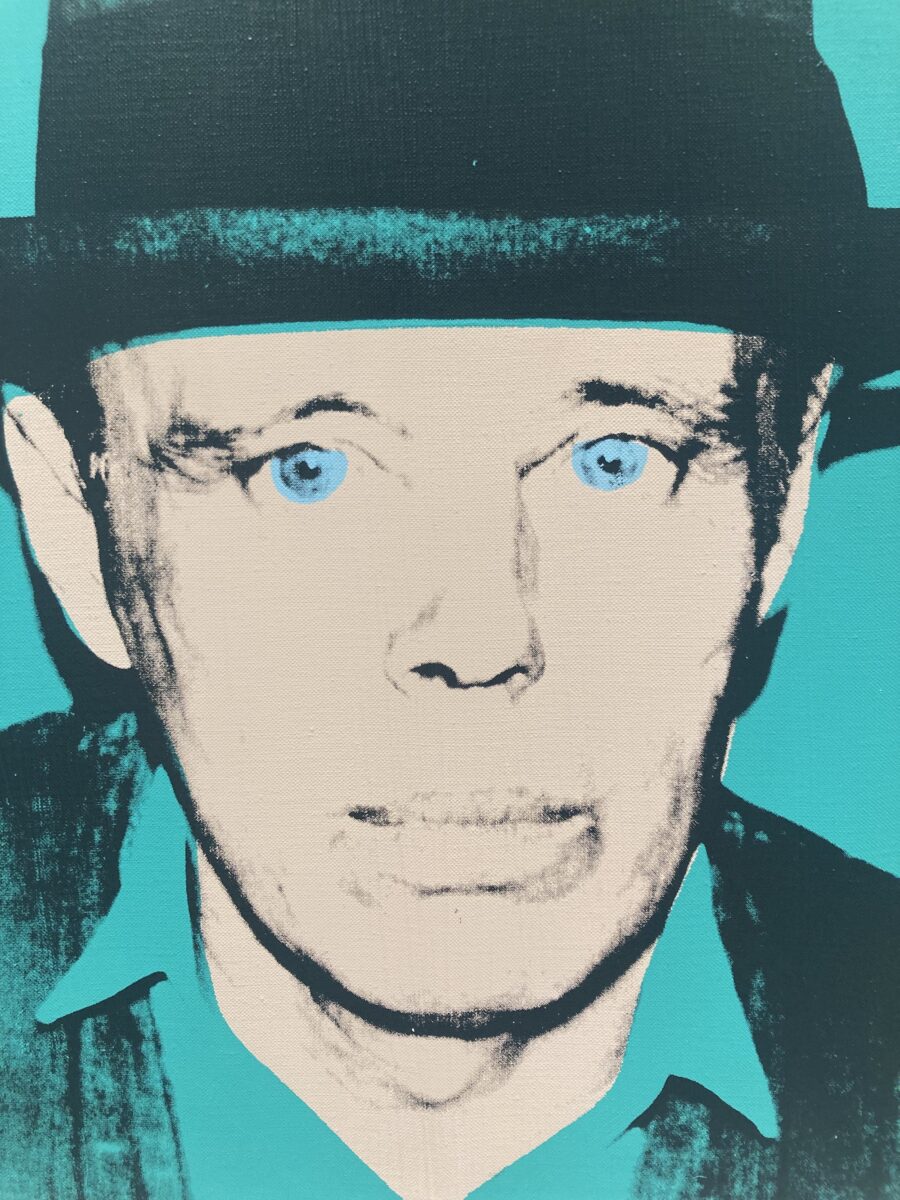

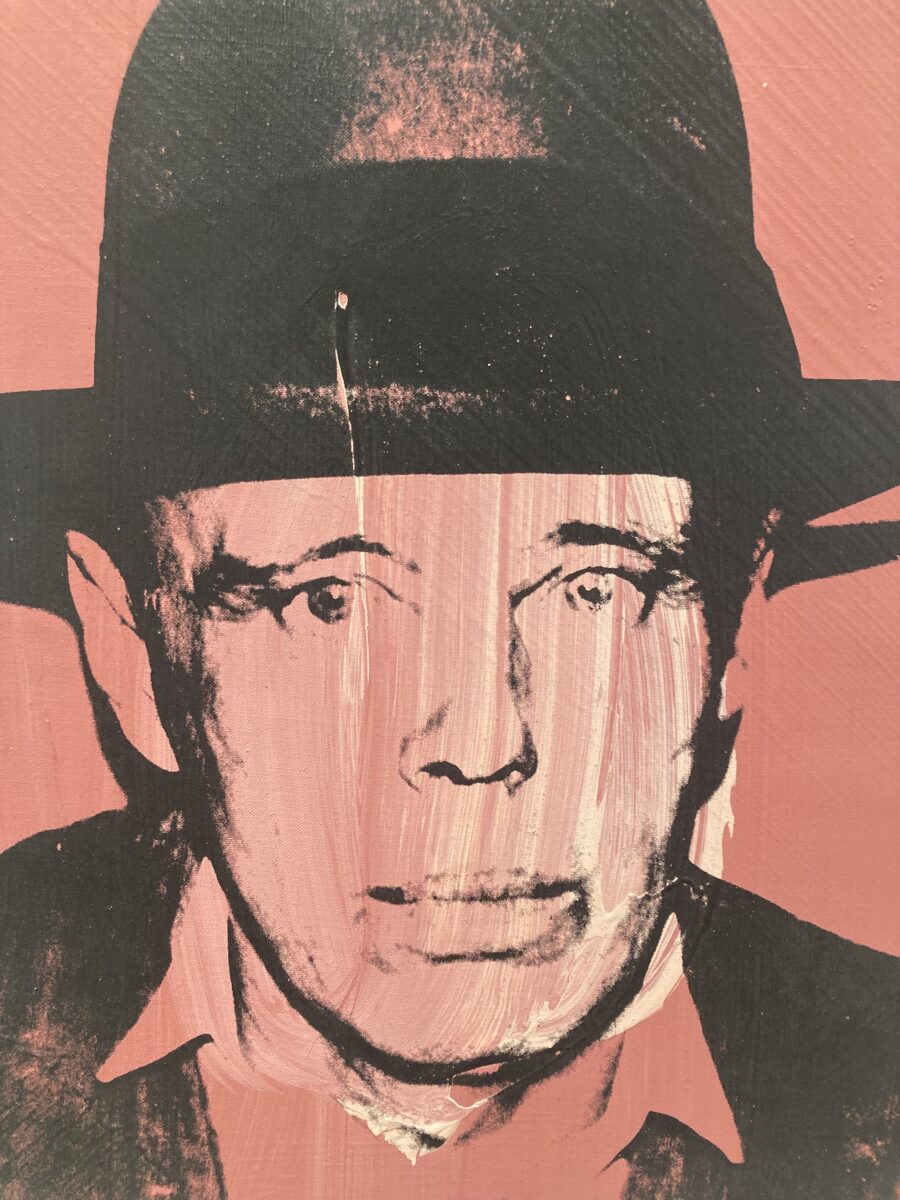

In any event, the conjuncture resulted in an array of portraits, each printed from the same photo but variably different in colour, texture, and application. The variety in repetition, or vs versa, is exemplary of Warhol’s obsession with reiteration and increasing renunciation of authorship throughout his career. Portraits line the ground floor galleries in Ropac’s largest flagship space, a restored townhouse on Dover Street, London. The collection of prints includes two drawings, which give a nod to the under-publicised reality of Warhol’s acute drafting skills – something that gets lost in the narrative as his most celebrated works facilitated faster and more effective repetition of form.

Bichromatic prints sometimes feature a daintily placed third colour over the iris, giving Beuys a pair of baby blue eyes that exaggerate the fairness of his face. He looks pretty, like a barbie doll or a beauty queen — for a social activist whose superficial image landed pretty far down at the bottom of his list of concerns, Beuys seems to have been passed through a Warholian filter. Warhol, who was known to be rather fixated on superficial beauty — speaking openly in his diaries about maintaining a slender figure, lamenting not being more conventionally beautiful — seems to have noticed Beuys’ effortlessly good-looking visage which went otherwise generally unnoticed by his followers— his full lips, long lashes, and delicately fluted nose — and made them readily apparent.

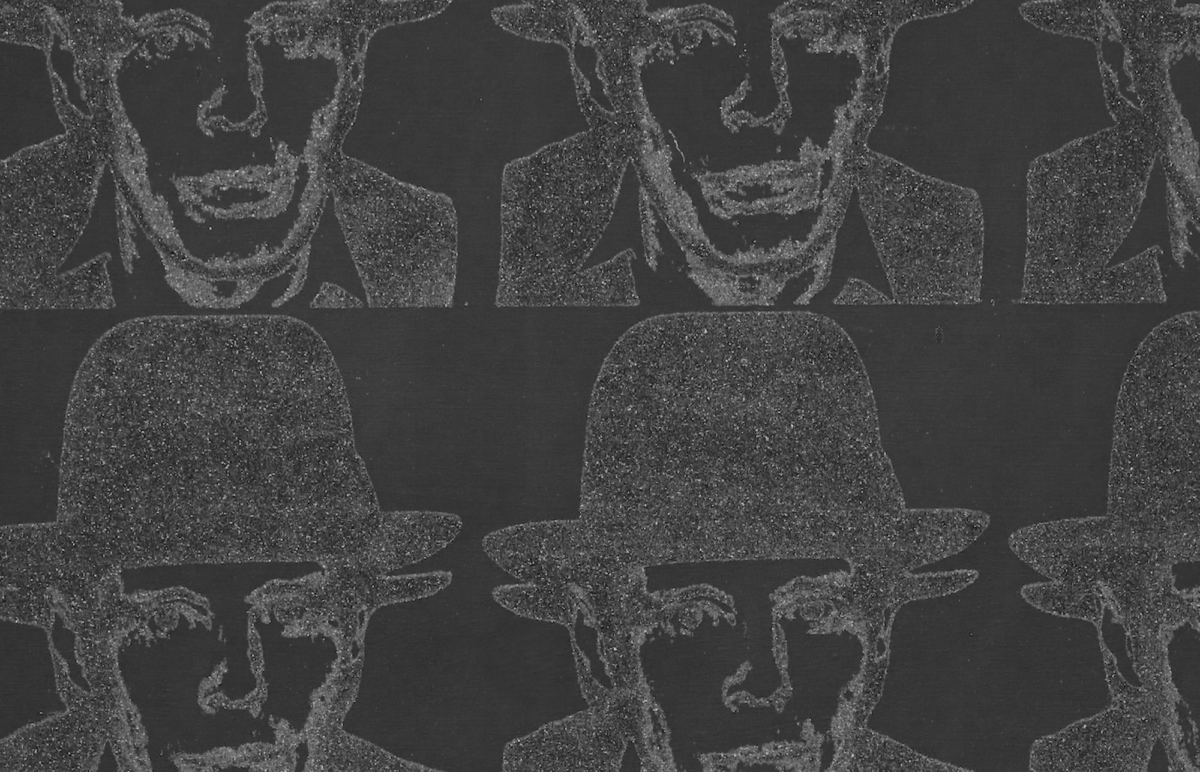

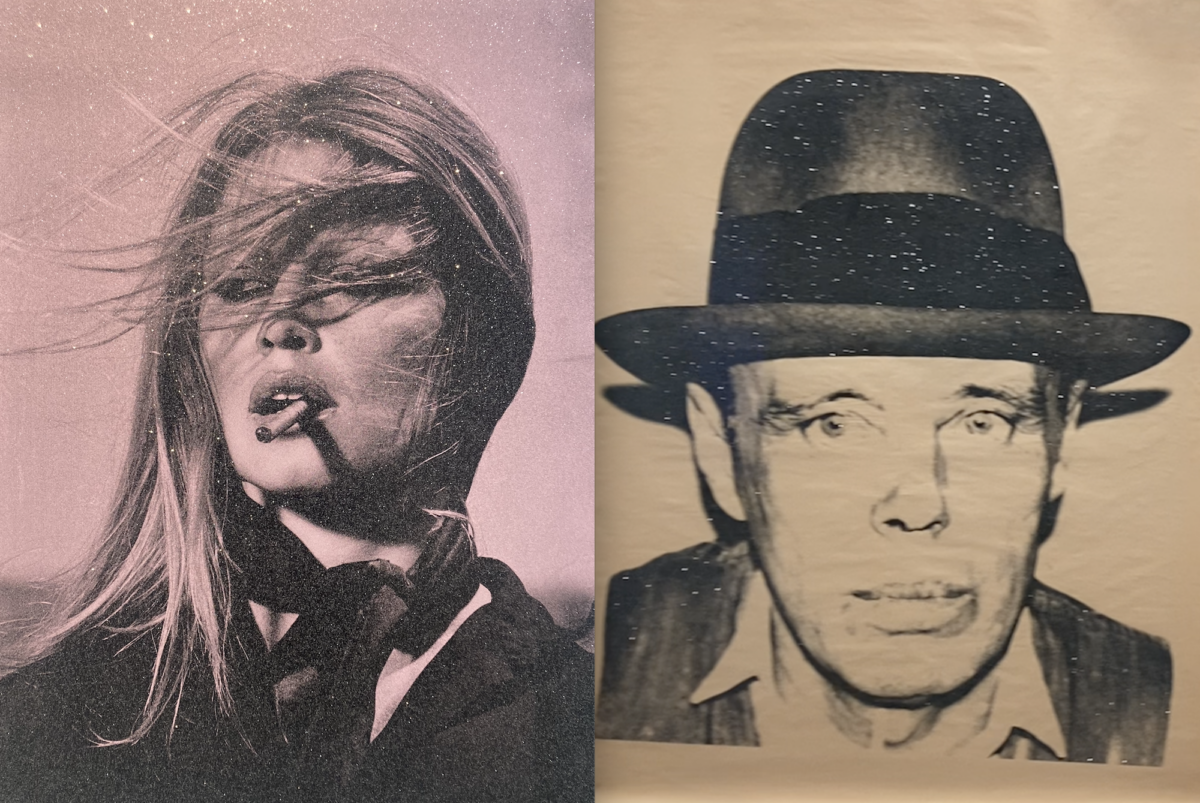

The collection also signals the beginnings of Warhol’s employment of diamond dust, which he began using earlier that same year. Essentially a gloried glitter, diamond dust is a powdery material whose chintz and tack is used in paintings and screen printing to achieve a luxurious look and embodies the materiality of mid-century American aesthetics. While the name sounds slightly more sophisticated than just craft glitter due to the obvious value implication of diamonds, the substance was in fact too dull for Warhol’s taste.

Instead of using actual diamond dust, he instead used a pulverised glass, continuing to call it diamond dust. The degradation in actual quality resulted in an increased reflectivity, making Warhol’s own brand of diamond dust far more glittery than the actual stuff, yet technically less expensive. While not initially intended as a social commentary, the decision proposes an interesting parallel between social connotations of what is desirable, coveted, and valuable, and the illusion of wealth and notion of a façade; all of which were strong themes throughout Warhol’s body of work.

Beuys was more interested in social revolution than diamonds or value formation, which is why the ageing of the diamond-dusted portraits in particular has been amusingly difficult from a conservation standpoint. While not all the diamond-dusted portraits are mounted under glass, many of them are, since the diamond dust attracts its own unwanted dust, resulting in an undesirable dulling over time. Most visible in raking light, which would most often be encountered in a home as opposed to in a gallery, the dusted prints require complicated and expensive removal of tiny (non-diamond) dust particles. It almost feels like Beuys’ spirit making a mockery of the dust with even more dust — poetic justice in the form of entropy.

It is because of their vastly different personalities yet unbridled fame that their liaisons continue to garner interest. The obsessive recalling of the encounter and ensuing work relationship between the two artists speaks to a societal infatuation with and glorification of celebrity culture and the kind of exponential aggrandising of value that comes from the combining and overlapping of celebrities with one another; a metaphorical diamond dusting of history. The resulting images, portraits of Beuys by Warhol, invariably tick all the boxes for value accreditation, and then some. Because the images represent the coming together of the two men, to possess or even lay eyes on one of the works might feel a bit like having or experiencing both a Beuys and a Warhol, encapsulating not only a moment in time but also multiple genres, social movements or birds with one stone.

People love to idolise Warhol’s interactions with artists. But is it really magic, or just inflated legacy? A better question is, why are we so obsessed with the coming together of famous people? Looking at them from the current day I see another couple of white cis-gendered men from the global North hogging the spotlight, yet again. Just sayin. Had Warhol met Russel Young, would their meeting be just as fawned over? Why aren’t we talking about Frieda Kahlo’s visit to the factory, which purportedly happened on the same day as Beuys’? Better yet, why aren’t we talking more about minorities at all, and the ways in which they have been facilitating men like this the entire time? That’s a rendezvous I want to hear about.

On my way back home, a stone’s throw from Dover Street I happened to wander into the newly opened Maddox Gallery, which recently moved into Simon Lee’s old space, only to discover a collection of diamond-dusted celebrities by Russel Young himself. It wasn’t planned, it wasn’t curated, it’s just what seems to sell, I suppose. It seems the recipe for success in Mayfair’s blue-chip circuit is a superstar and a bit of glitter. Am I wrong?

Andy Warhol The Joseph Beuys Portraits,14th —9th February 2024, Thaddaeus Ropac, Ely House

Russell Young, DREAMLAND, Maddox Gallery, Berkeley Street