Tate Modern, Bankside, London SE1 9TG

tate.org.uk Instagram: @tate

The opening of Tate Modern in 2000 is now seen as pivotal in consolidating the impact of the YBAs to bring contemporary visual art into a more mainstream place in our national culture. Herzog & de Meuron did a great job of converting Gilbert Scott’s Bankside Power Station without compromising its original architectural merits. The building has already been a gallery for longer than a power station – it was operative only from 1963-81 – with the main additions being the glass extension on the roof, and the ten-storey tower added in 2016. The underground oil tanks and the Turbine Hall, which once housed the electricity generators, are the most industrial spaces in art use. El Anatsui is the 21st artist to occupy the challenging 3,400 sq m, 26 m high Turbine Hall: he uses it well, though the iconic installations remain Olafur Eliasson’s sun (opening in 2003); Carsten Höller’s slides (2005); Doris Salcedo’s crack (2007) – the scars from which can still be seen; and Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds (2010).

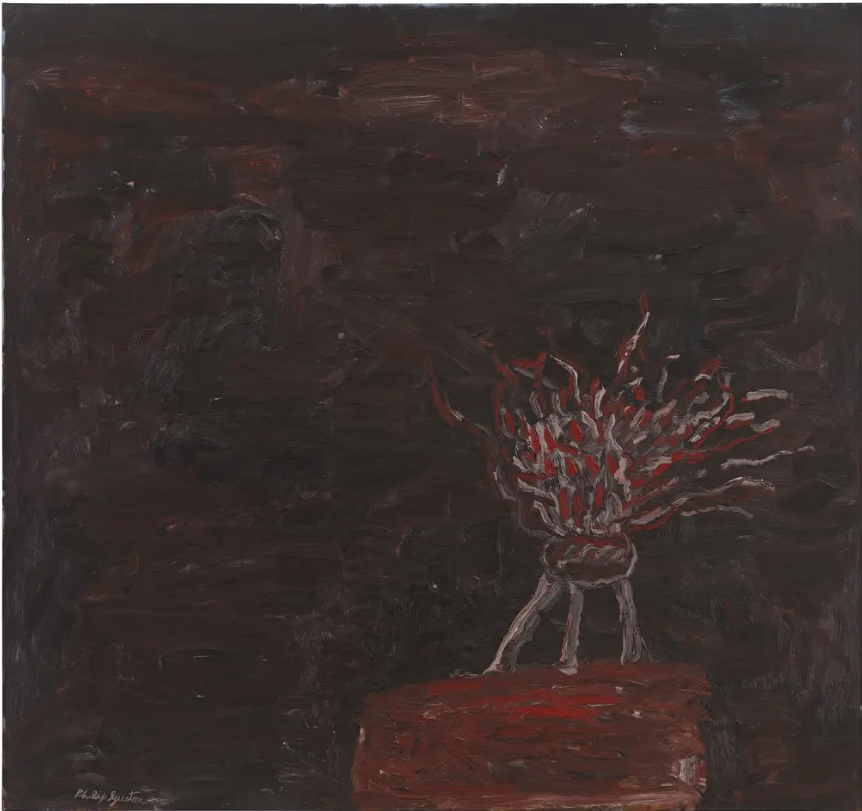

Given lead times, it’s too early to tell whether the 2023 switch from Frances Morris to Karin Hindsbo as Director will make a difference to the programme, but the current Philip Guston show – controversially postponed from 2020 – is one of the best in Tate Modern’s history: comparators might include solos by Donald Judd (2004), Gerhard Richter (2011), Henri Matisse (2014), Agnes Martin (2015), Robert Rauschenberg (2016), Pablo Picasso (2018) and Rebecca Horn (2020); or the spot-on group shows ‘Zero to Infinity: Arte Povera 1962–1972’ (2001) and ‘Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power’ (2017). And the 2024 programme bodes well: Yoko Ono, expressionism, Mike Kelley, Zanele Muholi, Anthony McCall…

London’s gallery scene is varied, from small artist-run spaces to major institutions and everything in between. Each week, art writer and curator Paul Carey-Kent gives a personal view of a space worth visiting.