Not long ago, when the reigning culture in American art schools was one of self-expression, even to the point of valuing art as a straightforward presentation of one’s emotions, I would tell a story about a student introducing a critique of their work with something on the order of, “I was very sad after my recent breakup, so my paintings this semester are all deep brown.” When I repeated that to a recent graduate of a major art school, adding that it was of course exaggerated to make a point, he replied with a laugh, “You mean you weren’t at that critique? I was there!”

It is not a long stretch from asserting art as the near equivalent of one’s emotions to thinking that the purpose of making art is to assert one’s identity. I once read on the Artforum Website a graduate student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, from which Decheng Cui earned an MFA in 2020, state approvingly that graduate critique consisted of “the performance of the self in front of the paintings.” This wording may not be exactly verbatim, but when I tried to check it, a search for “art” and “the performance of the self” generated about thirty million hits.

A bit of a shift in notions of the self has occurred in recent years. In response to the terrible forms of bigoted discrimination that so many marginalized persons have suffered, the assertion of group identity, still a form of the “performance of the self,” has become a major subject in art making, criticism, and curation.

Decheng Cui was born in Qingdao, China, in 1990. During undergraduate education in China with a major in oil painting and a practice producing representational work, he encountered the work of Georges Seurat in an art history class. Without access to the original paintings, he misunderstood the source of their “unique visual experience,” and it was only after seeing major works in person at the Art Institute of Chicago that Cui began a half-year of experiments with “color mixing.”

The key to understanding artist statements is not to ask whether one agrees or not, but rather, is the statement a pathway that might be productive of a certain kind of artwork, perhaps of a type different from the dominant practices of our era? Cui’s statements, “Emotions are not sacred, independent or superior to thinking, and “Human beings are unwilling to abandon the sanctity of emotions because of their arrogance,” resonate with me. They ought to resonate with anyone who has attended art school critiques at which the “performance of the self” serves as a substitute for art works whose forms speak out of their own inner complexities.

The relationship between human emotion and art work, which varies from artist to artist, has been questioned by key modernists. The poet Ezra Pound, writing of late nineteenth-century classical music, addressed “the whole flaw of impressionist or ’emotional’ music as opposed to pattern music. It is like a drug; you must have more drug, and more noise each time…” He counterposed this to Bach: “I do not mean that Bach is not emotional, but the early music starts with the mystery of pattern… with something which is, first of all, music, and which is capable of being, after that, many things. What I call emotional, or impressionist music, starts with being emotion or impression and then becomes only approximately music. It is, that is to say, something in the terms of something else.” The painter Paul Cézanne is described in the essay Cézanne’s Doubt, by Maurice Merleau-Ponty: “In La Peau de Chagrin Balzac describes a ‘tablecloth white as a layer of newly fallen snow, upon which the place-settings rise symmetrically, crowned with blond rolls.’ ‘All through youth,’ said Cézanne, ‘I wanted to paint that, that tablecloth of new snow…. Now I know that one must will only to paint the place-settings rising symmetrically and the blond rolls. If I paint ‘crowned’ I’ve had it, you understand? But if I really balance and shade my place-settings and rolls as they are in nature, then you can be sure that the crowns, the snow, and all the excitement will be there too.'” Both artists strive to replace art born out of pure emotion with creation that begins with the pursuit of form, and this is an attitude much needed today if only to correct an imbalance in the age of the selfie of focus on the particularities of one’s identity.

Cui stresses reason over emotion, and reason over individual or group identity. He aspires “to understand and use the universal laws of nature,” writing of his recent art, “Through reason, people have created the most powerful belief in human history, science. The core of this series of works is…belief in science.”

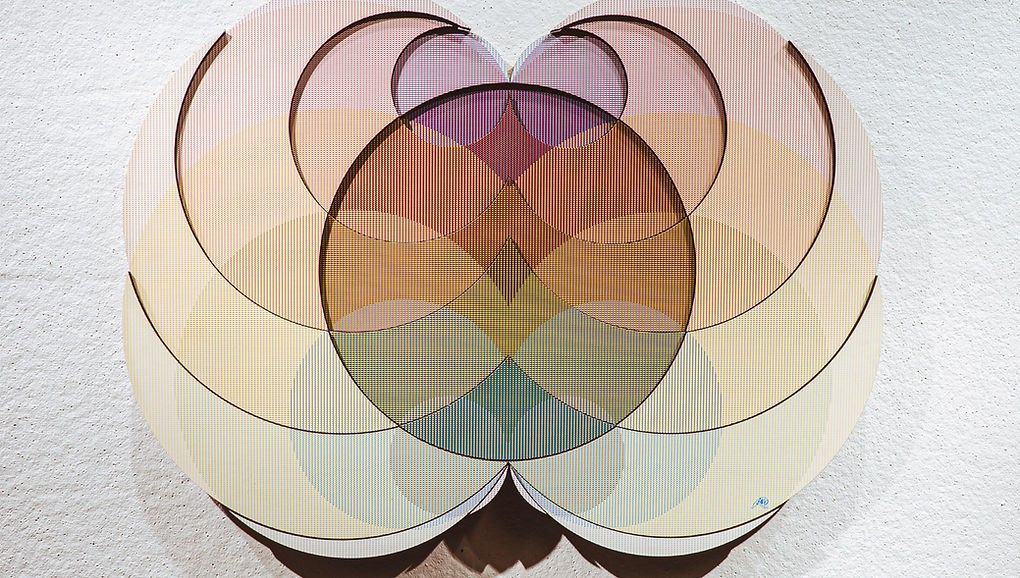

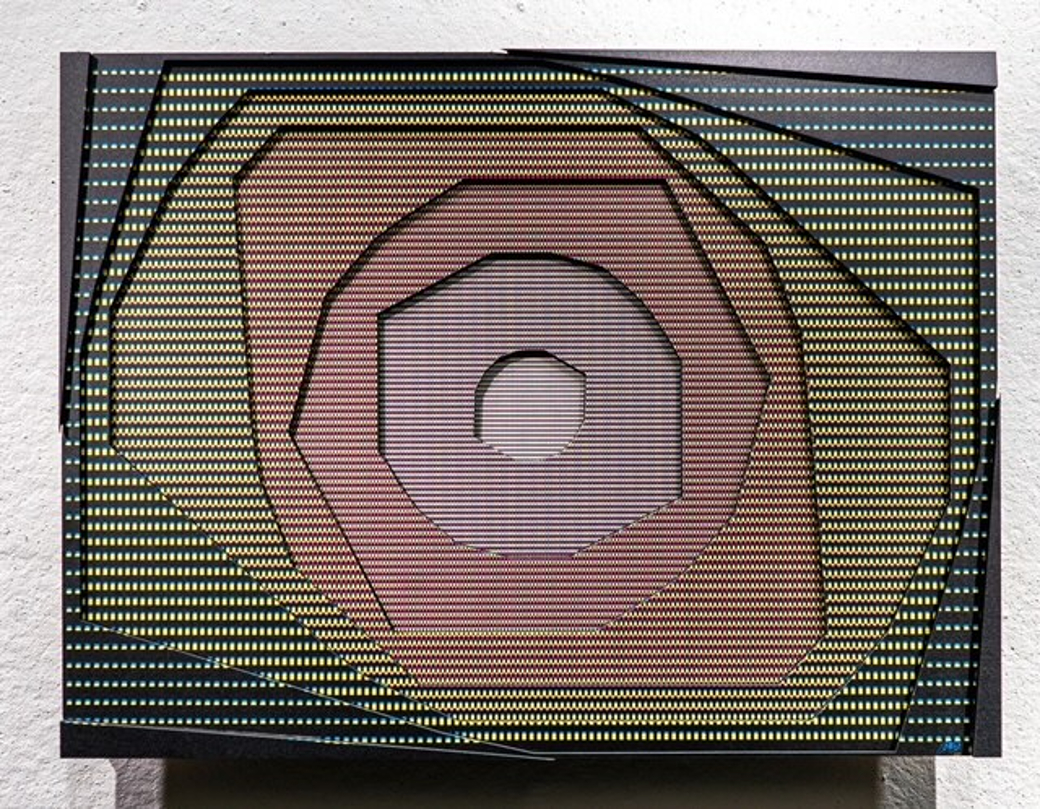

Cui’s mixed-media sculptures incorporate digital prints using myriad tiny repeated dots, and by juxtaposing dots of several colors he produces a double effect: the works look very different close up and from several yards away, from which position the colors blend. His sculptural shapes include both symmetries and irregularities. One of the more symmetrical, Heart Line_5, is vertically but not horizontally symmetrical. Is there a tiny hint of a face in the central circle? The surfaces are covered with thousands of dots, rectangular pixel shapes, in several different colors. (X+X^2)^2 is organized around six concentric polygons, each of which appears to have been rotated with respect to the next, creating dynamic collisions between lines and corners angled with respect to each other. In Heart Line_3, triangles and rectangles seem to spread out from a point at top center making a shape a bit like that of an opened, or opening, fan. The geometries of all of these mix regularity and surprise, sometimes seeming a bit unpredictable in ways that call attention to themselves. Cui’s tiny colored squares demand attention as well. One would have to stand far back for them to seamlessly blend. More often, they engage, drawing the viewer closer. There is something a bit mysterious about their repeating mixes of colors. The resulting mostly muted hues never seem familiar. They reveal their mix of colors within, and also between, panels, so that there is a nearly bright orange at the bottom center of Heart Line 3 with an increasing darkness at the sides and above.

Cui evades the trap of the emotional self in part by using mathematical equations to determine the shapes of his works and the colors and placements of his dots. There is surely an artist present here, but one who chooses to stand back from one part of the psyche, in order, it seems, to nurture another part, that of logic and reason, qualities too often underemphasized in art works today.

That “other part” also results, from the ways Cui makes use of it, in the complex, nearly paradoxical experience of viewing perceptually challenging art works in time. Even more than for most art, these are not pieces to view in short glances. There is a mix of harmony and dissonance between the sculptural forms and the complex fields of dots that cover them. Both feel logically organized, but on slightly different principles, utilizing presumably different equations. Instead of the viewer feeling, as with much mediocre art, a kind pf decorative pointlessness, in front of a Cui work the question, “What’s the point,” becomes almost urgent. One intuits, in other words, that there is a “point.” Cui’s shapes neither suggest actual objects, that hint of a face ultimately proving no more than a hint, nor the kinds of vapidly formulaic products of the lesser examples of minimalist art. His strange and diverse geometries mixing symmetry and asymmetry, the irregularities of, for example, the roughly concentric polygons, suggest that there is a secret to unlock behind each of them at the same time that they deny history and psychology. Panels are layered atop each other while their surfaces, despite standing at different levels of depth, combine to make a sort of color wheel in F(X^3+11X), creating an oddly broken emotional edginess without evoking any specific emotion. More “content,” such as evocatively charged imagery rather than colored dots, could easily transform Cui’s cool and restrained work into searing melodrama, destroying what is most interesting about it in the process. The fact that the viewer even wonders about emotion, notices the “edgy” feelings of the larger shapes and dot patterns and the ways in which they sometimes collide, suggests hidden feelings that are never brought to the surface. We receive some of the effects of emotion without any specific feelings being evoked.

Indeed, there is at least in part a psychological reason for Cui’s neutral-seeming style. “I fell in love with creative art,” he wrote, “because I can feel that when I create art, I am less afraid of death. In fact, I am a person who is very afraid of death. I used to think of the fear of death in the middle of the night,” which “caused me insomnia.” Perhaps a shade of that fear survives in these works.

Mathematics itself rarely has such an edge. A theorem, and its proof, can have their own beauties, but rarely is there a hint of psychological expression. However, I did find myself thinking of one other period of art when viewing Cui’s works: the magnificent Song Dynasty landscape paintings that are, for some, the high point in the long history of Chinese art. In their restrained lines, repeated brush strokes, empty spaces, and love and care shown for the large forms and small details of nature, there lies a magnificent neutrality, the artist’s self almost vanishing, at least by today’s standard for an artist’s openly evoked self, in the face of nature. It is fitting to our technological era, while also surprisingly refreshing in in the climate of our current art world, that the reverence expressed toward nature by Chinese artists of a millennium ago is transformed into a reverence for science, mathematics, and logic in Cui’s art.

Guest Author:

Fred Camper is an artist, teacher, and writer on art and cinema who lives in Chicago.