In 2016, The Guardian published an article by critic Kyle Chayka titled ‘Same old, same old. How the hipster aesthetic is taking over the world’. The so-called hipster aesthetic modestly encompasses several design trends, and can essentially be reduced down to “Industrial furniture”, mid-century modern, wooden floors, and “Edison bulbs”. This craze for mass-produced minimalist design became a global phenomenon spurred by the proliferation of Ikea and amplified with the rise of Airbnb.

Soon, an ultra-uniform design pattern emerged across the world. Whether you were staying in Georgia or Chile or Paris, a sleek, elegant and restrained apartment could be found. Several years later the novelty is worn off to the point of total stylistic obsolescence. Could we be ready for a new design revolution, perhaps an “old” design revolution?

The Memphis Group emerged at the start of the 1980s under the leadership of Ettore Sottsass, composed of over a dozen mostly Italian artists and designers. The group was united by a shared ethos of seeking to buck the minimalist, modernist trend and create furniture that was antithetical to the day’s conception of good taste. Echoing the current global indifference – to a point of universal dissatisfaction – with mediocre Modernist-industrial design, the work produced by the Memphis group sought to imagine an antidote to the proliferation of bland, corporatized Bauhaus-style furniture of the era.

The Memphis group still drew from Bauhaus-inspired principles of utilizing ordinary, low-cost materials towards loftier design aims, though through decidedly more iconoclastic strategies. Stainless steel and glass were eschewed for plastic laminate and bold, shockingly bright color schemes. Bad taste was thus fully embraced for the designers of Memphis, as were notions of kitsch and craftsmanship. Memphis was more than just a set of radical objects though, it was also designed with a spiritual philosophy in mind.

Some of the pieces are given names, have human-like forms, and seem to have lives of their own. In this sense, the inanimate are filled with life, and each evoke unique emotions, stories and meanings. The more anthropomorphic objects have playful personalities and elicit an affective response in viewers who can’t help but to begin to engage with the objects too in a playful manner. Thus the impact of design is demonstrated in the way we mirror the conditions put in front of us.

This particular iteration of emotional, effectively oriented post-modern design has much resonance with Mathias Goeritz (1915-1990) and his theory of Emotional Architecture.

Born in Germany, Goeritz emigrated to Mexico after the Second World War and established himself as a regionally idiosyncratic critic of the homogenizing effects of Modernism. In 1952 he penned the Emotional Architecture Manifesto, which argued for the prioritization of spirituality and feeling over the practical and functional purposes of both art objects and the built environment. In this manifesto, Goeritz wrote:

The man of the 20th century feels crushed by so much “functionalism”, by so much logic and utility within modern architecture…He asks – or will have to ask one day – for architecture and its modern means and materials, a spiritual elevation; Simply put: an emotion, as it was given in its time by the architecture of the pyramid, that of the Greek temple, that of the Romanesque or Gothic cathedral – or even that of the Baroque palace…Only by receiving true emotions from architecture can man consider it again as an art.

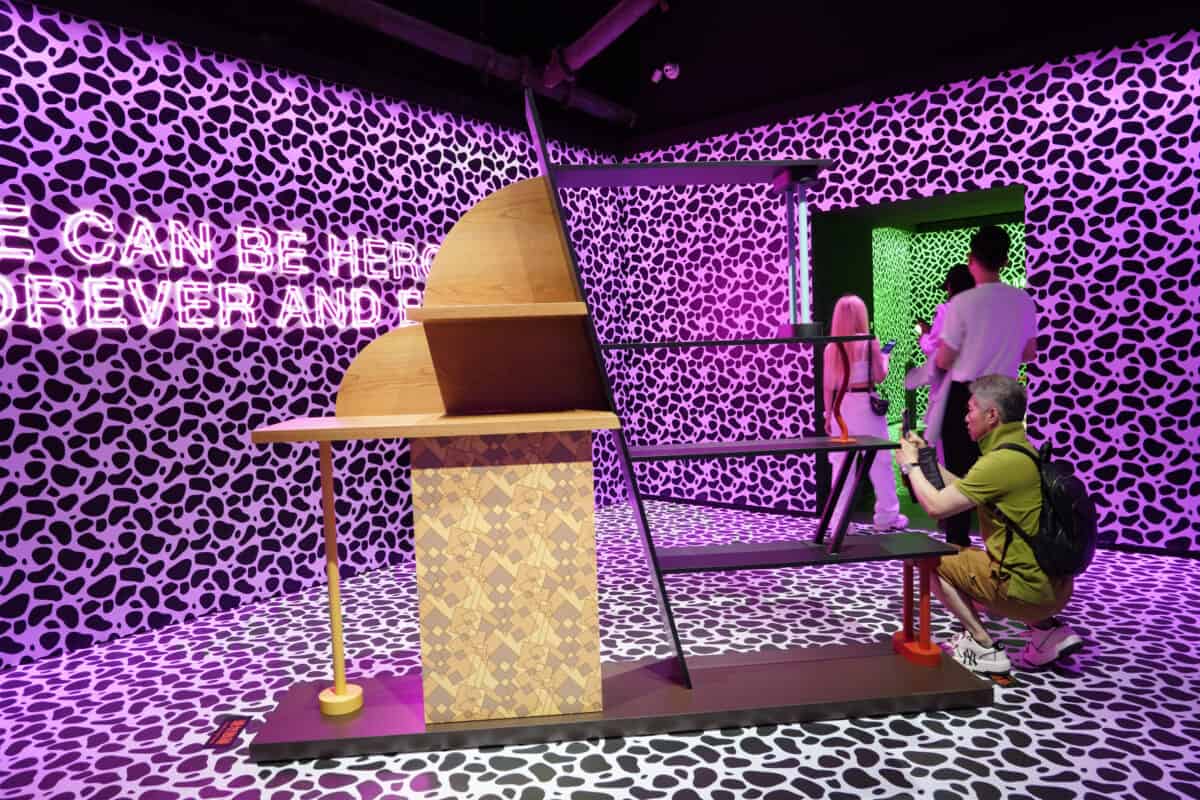

Goeritz’s architectural works and visual art thus sought to create a visceral, anti-rationalist, emotional sentiment amongst viewers. The same can be said of the design objects of the Memphis Group. David Bowie, a famous early client of the group, described “the jolt, the impact, created by walking into a room containing a cabinet by Memphis.” Memphis cabinets–flagship items of the furniture group–were indeed a shift from the soft lines, glass, and muted colors of much late Modernist 1970s design.

Horizontal and diagonal shelving, built as if taken directly from an imaginative designer’s sketchbook, creates a peculiar, versatile structure of varying angles to cradle books or art objects. Contrasting the structure is the faux-terrazzo vinyl finish, bridging high- and low-brow design in an innovative, bold gesture, printed in both muted and flashy color schemes. These objects, existing in a liminal space between art, design, and something alien, feel at once bespoke and unknowable.

The contrast that the work of Memphis presents to the staid, sleek object design of Minimalism and Modernism is marked, and has much to do with its utilization of ornament–an aesthetic antagonist of the global hipster design style that is so prevalent today. The aesthetic debate around ornamentation, excessive features on architecture and furniture is a well trodden path in Art History. In the nineteenth century, critic John Ruskin famously celebrated the “Gothic” style, an ornate architecture and design trend which spread throughout Europe during the Middle Ages. The nature of ornamentation and decoration was loaded with moral values in the nineteenth and early twentieth century with some writers like Ruskin deeming it virtuous.

Others, like the architect Adolf Loos, went as far as to describe it as impure and immoral. In today’s 21st Century, an era characterized by ‘cool’ amorality and a lack of spiritual thoughtfulness, the silent majority may appreciate a return to ornamentation and decoration, and all of the affective and philosophical trappings which accompany its embrace. In fashion, a growing interest in sustainable, handmade, and slow garment production has emerged due to criticism of the polluting fashion industry. Perhaps next we are due to see this trend continue into furniture, with bespoke, unique and thoughtfully ornamented pieces like those produced by the Memphis group–and exemplified by its delightful return to public interest and taste.

MEMPHIS AGAIN Directed and curated by Christoph Radl – July 30th, 2023, Modern Art Museum (MAM) Shanghai. mamsh.art

About the writer

Shai Baitel is a creative and artistic director with extensive experience in the fields of art and culture in the United States and abroad. He serves as the Artistic Director for the Modern Art Museum (MAM) Shanghai. Baitel also leads Creative Philosophy, an agency and advisory for concepts and projects in these fields.

Baitel has a keen interest and expertise in the intersection of art and fashion. He has written extensively and analysed how Gucci, Valentino, and other brands are examples of that dialogue. Under Baitel artistic direction, MAM Shanghai has featured fashion projects with Anna Sui, Trevor Andrew/GucciGhost, and others. He has also been selected recently to conceive the first retrospective of the work of Christian Lacroix.

For the Ministry of Culture of Saudi Arabia, Creative Philosophy conceived the StreetArt Festival ‘Shift22’ (Riyadh, October 2022).

For the Modern Art Museum (MAM) Shanghai he has conceived exhibitions that include Bob Dylan: Retrospectrum (2019), Zaha Hadid Architects-Close Up (2021), and Neo Golden Age (2020), featuring Philip Colbert and Trevor Andrew.

Baitel envisioned, co-founded, and helped Mana Contemporary, the largest and most comprehensive arts center of its kind, grow into its current form as an internationally recognized arts destination.

He has worked with and presented projects with many museums including the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York City), the Patricia and Philip Frost ArtMuseum (Miami), the Museum of Contemporary Art of Rome (MACRO), and MAXXI, the National Museum of 21st Century Art (Rome) (December 2022)