Drawing its title from Caroline Evans’ seminal text ‘Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity, and Deathliness’, the current exhibition at Rose Easton (formerly Moarain House) titled, ‘On the edge of fashion’ explores the symbiotic relationship between fashion and art, while interrogating fashion’s capacity to “investigate the domain and configuration of incoherence, discontinuity, disruption and disintegration”.

It looks to fashion as a tool of resistance, a unique yet almost universal lexicon through which the individual may present themselves against the mainstream. Caroline Evans described fashion design through the language of psychoanalysis in an allusion to the pathologization of difference; she wrote “fashion design…seemed to function like a hysterical symptom that could articulate current concerns” in reference to the rebellious catwalks of the 90s such as Alexander McQueen’s canonical show, Highland Rape. Evans heralded the power of fashion to construct identities that speak back, presenting the way we dress as a subtle tool that, whether consciously or not, belies cultural concerns surrounding class, capital, empire and gender.

At a time of intense social upheaval – the cost-of-living crisis, post-Covid and post-Brexit fall out, war and political instability – individuals often look to creative outlets to present critique or grapple with the resultant plague of instability and anxiety. Through art, fashion, and the intrinsic overlap between these not so distinct categories, the artists in ‘On the edge of fashion’ find their voice.

Coinciding with London Fashion Week, a moment when the global fashion crowd descends on London, the exhibition takes account of the inherent dichotomy between fashion as a tool of resistance, and its relationship with luxury and access. Through art as a mediator, it openly looks back upon the lacuna between the fashion industry and fashion as an individual signifier of identity. Stepping over Haute-couture, exclusive front rows, global markets and the luxury sector, the artists look to fashion’s personal implications, wrestling with contemporary social, political and cultural anxieties that directly impact their own lives.

The exhibition features the work of, Arlette, Alfa Bransfield, Aaron Ford, Jonah Pontzer and Mary Stephenson – I spoke with Alfa and Aaron to dig a little deeper into this timely exhibition and their works on show.

Q: The show has a unique and glamorous feel, largely brought forth by the pink carpet along with the subject matter itself. How do you think the exhibition as a whole both promotes and deconstructs the ‘allure’ of high fashion?

ALFA BRANSFIELD: I was impressed with Rose’s proposition that this show could be as much a mirror held up to art as it was to fashion. Specifically, that art, or should I say the art _world_ (as distinct from the art _community_) acts like it’s exempt from some of the mores and frivolities of the fashion world, when in fact it is totally complicit and in many cases in more and more direct and transparent ways. The major fashion houses or at least their holding companies, Prada, LVMH etc, are some of the biggest global investors in art, for example. I was reminded of the famous scene from Ab Fab in which Eddie, the consummate fashion victim, walks into a gallery in Mayfair and tells the bitchy-resting-face gallery girl ‘you can drop the attitude, you just work in a shop, you know?’

Q: The exhibition engages dynamically with both past and current cultural discourse. It looks to transformative moments in the history of fashion such as Alexander McQueen’s canonical 1885 show, Highland Rape, while also coinciding with fashion month and its associated media fervour – thinking of the Schiaparelli show. How do you think the exhibition positions fashion as a medium that can be mobilised for change? Do you think fashion’s capacity as a mode of protest has changed considerably since the 90s?

ALFA BRANSFIELD: I think what’s interesting about fashion is that it sits at this knife-edge axial point between want and need; desire and necessity and, as we’re seeing with the current incredible spate of industrial strike action, the confusion between these two things is usually the breeding ground for any kind of protest in the first place. The existential nature of ‘wanting’ verses ‘needing’ is something I am thinking about all the time as someone who has chosen to live their life dedicated to the utterly farcical pursuit of being a contemporary artist, which can swing very quickly day to day from feeling like I’m on some ascetic spiritual mission to feeling like I’m a product designer for a grotesque, carnivalesque world that I never intended to enter into in the first place.

I think the reason McQueen captured and continues to capture people’s imaginations is because the romantic story of this ungainly gay chav from the East End using his dole money to put on his first shows to very quickly becoming the head of Givenchy in a few short years straddles this exact divide. There is something Shakespearian in the fable of his desperation to express something vital which, when expanded, upscaled and industrialised at such an alarming pace, was ultimately his undoing.

Q: Underlying much of the work is a sense of social, political and cultural anxiety – how do you think these tensions are explored in your work?

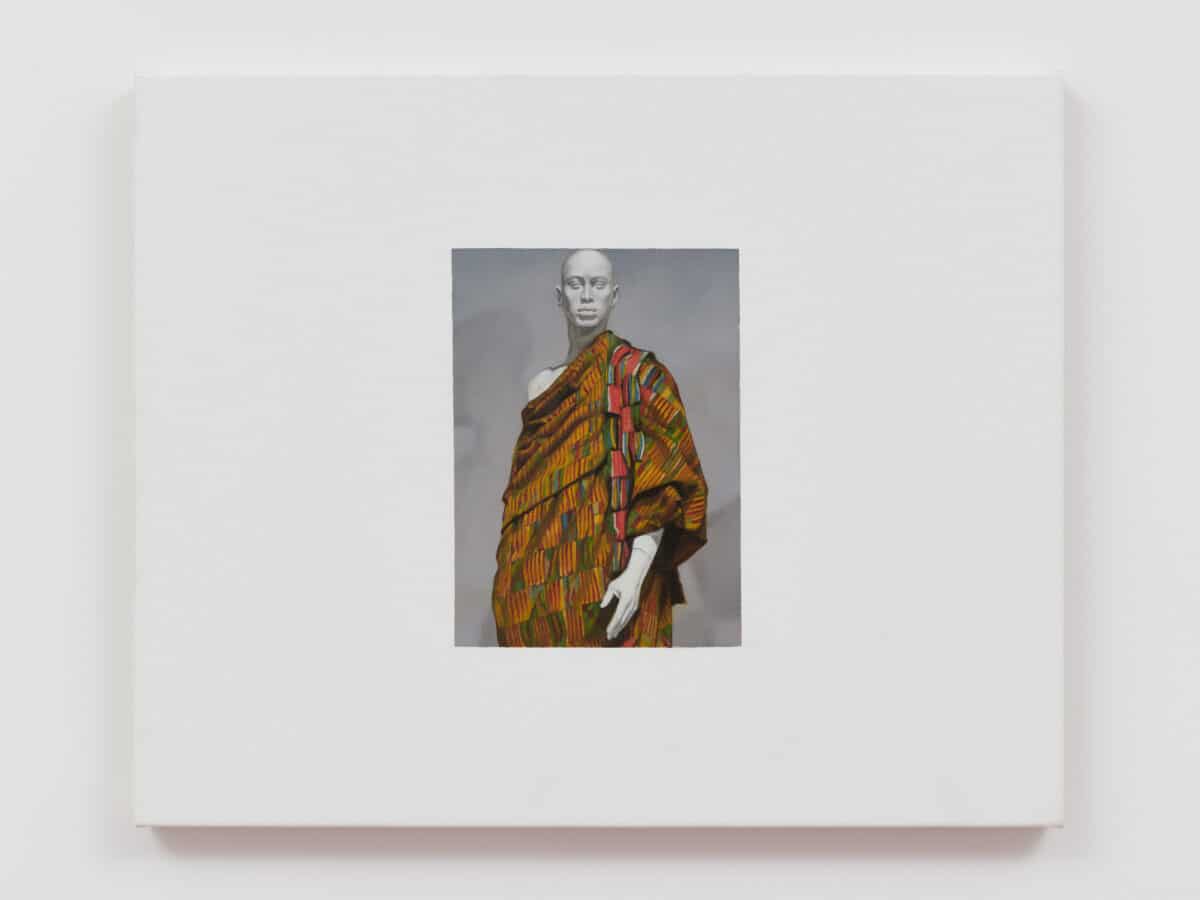

AARON FORD: I find it is interesting to explore these anxieties in conjunction and in opposition to what we take to be familiar or safe. To me the mannequin in the painting ‘Figure’ carries with it a vague sense of threat and political alienation. Mannequins are almost always an inhuman grey white colour which is perhaps supposed to denote neutrality; in actuality however, it only makes them even more uncanny, a form of human alien from no-place or no-time.

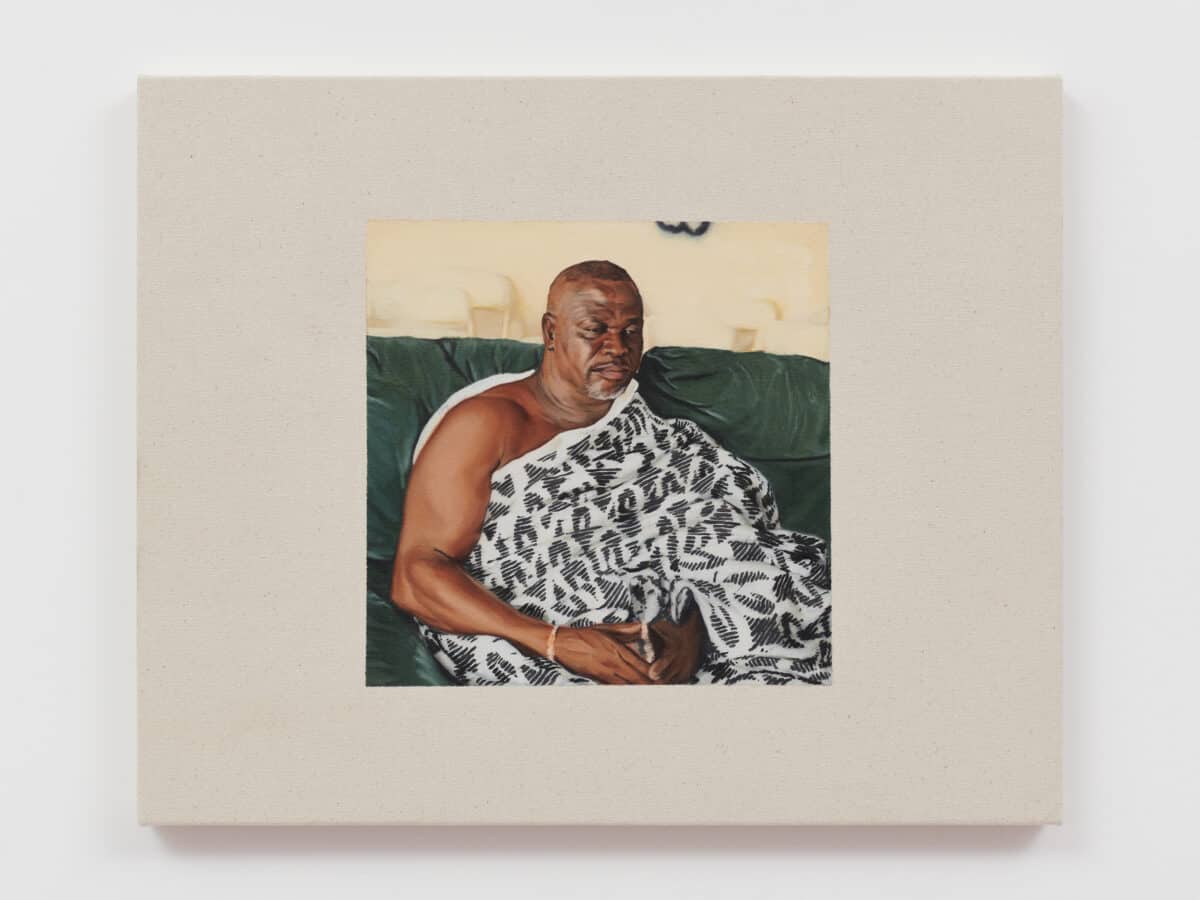

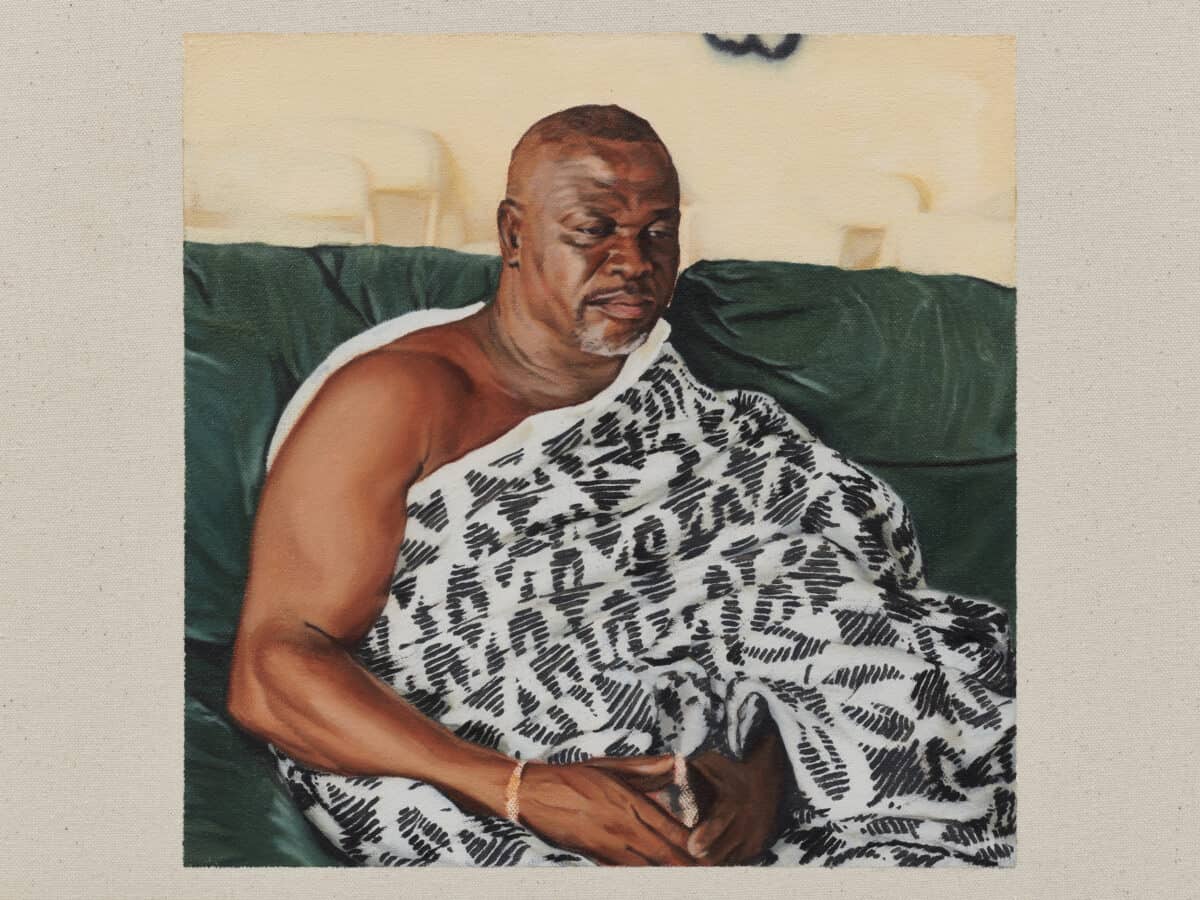

Contrast this with ‘Man Sitting Down’ and what I hope is a sense of softness or ease, a man comfortably sitting on a sofa surrounded by the gentle colour of canvas. This potential of contradiction seems to extend beyond the space between the two paintings. It was a happy surprise to discover that ‘Man Sitting Down’ and Jonah Pontzer’s Cancer Son created a lovely corner in the back right of the room, creating two opposing spaces which change contextually. At once being anxiety inducing and comfortingly ordinary, the space teased behind Pontzer’s screen conceals what the window facing out to everyday urban life reveals, and vice versa.

Q: The exhibition as a whole acts almost as an installation whereby the artworks on show and the space itself speak to one another to create an immersive environment for the viewer. How do you think your work operates in conjunction with the other pieces on show? What kind of dialogues emerge in the gallery space?

AARON FORD: One interesting aspect of the exhibition which arose during the install is the amount of rigour placed on looking at simple elements of the fashion of domesticity. When taken altogether in ordinary life objects can become ubiquitous, but when studied individually their peculiarities begin to come through.

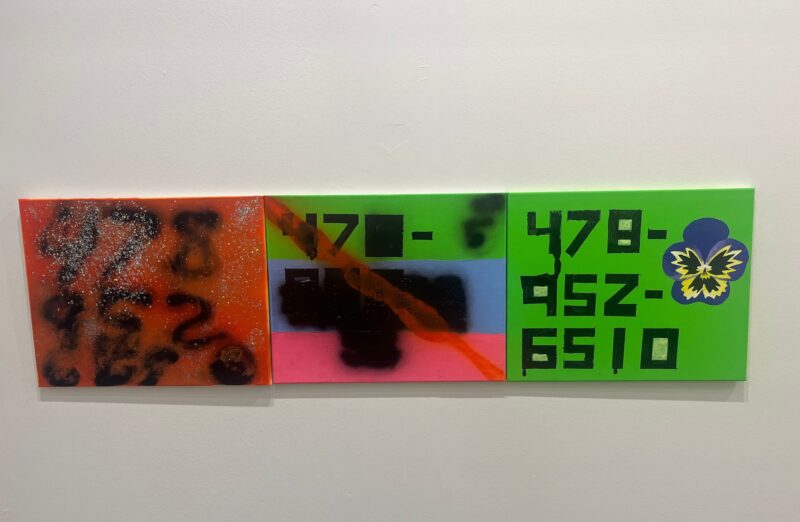

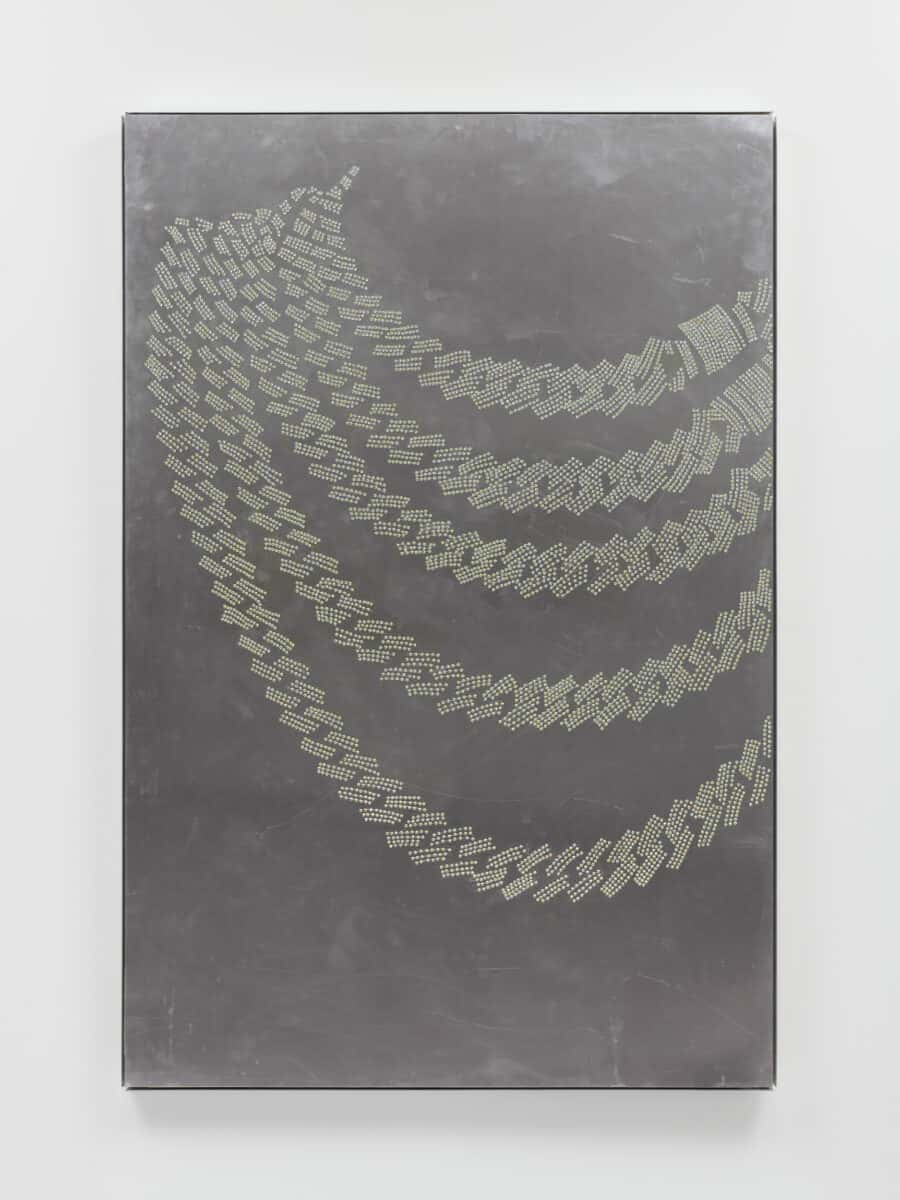

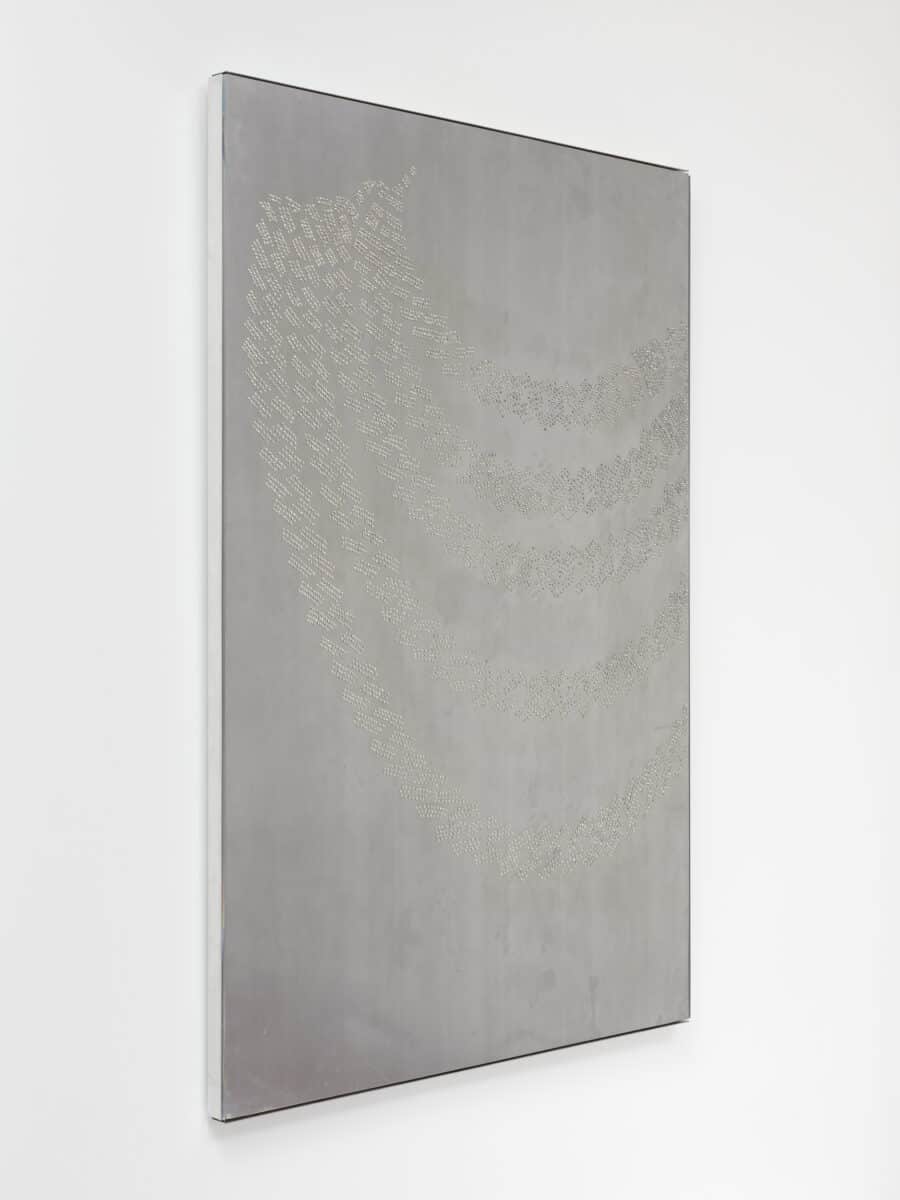

Mary Stevenson’s piece ‘Citrine Green’ gives an abstract sensuality to folded fabric or a lemon squeezer. The transparent crocodile skin glaze Jonah Pontzer applied over ‘Cancer Son’ serves to both highlight and obfuscate. Arlette’s XXXL ‘Buckle Belt’ gives a vague sense of sexual promise to a belt buckle. Alfa Bransfield’s perfectly placed diamantes in ‘Three (Thug Votive)’ seem maddeningly meticulous. My painting ‘Figure’ shows the extra-terrestrial regal-ness of a mannequin. This may have just been my interpretation, but the pink floor adds to this sense of slightly fraught cosiness. While it feels inviting and warm, the amount of scrutiny and intense concentration placed on the objects in the show makes the space feel distinctly charged.

Q: The exhibition draws its title from Caroline Evans’ seminal text Fashion at the Edge, she writes “On the edge of discourse, of civilisation, of speech itself, experimental fashion can act out what is hidden culturally”. In relation to your own work, what might this come to mean? How are ideas presented by Evans perhaps alluded to or explored in your practice?

AARON FORD: In my own work, I am always searching for iconographical symbols, motifs or trends that migrate culturally. As I am a painter, I use painting as a reference point when locating these phenomena, but fashion is a perfect vehicle for this kind of migration too, and as Evans points out can be used to unearth what is ‘hidden’.

For my paintings, ‘Man Sitting Down’ and ‘Figure’ I was made aware of two types of traditional Ghanaian cloths, these being kente and adrinka cloths. Here I found a perfect example of this cultural transference and subsequent dislocation. The cloth itself, and the patterns and colours that form its make-up have transferred their meaning over time. From once serving a specific ceremonial function amongst a group of peoples within Ghana, through becoming an unofficial symbol for Pan-Africanism it now acts as a clumsy universal signifier for Africa. This is a uniquely visual phenomenon and displays how the formal qualities of an object can take on new meaning and supersede itself, reaching the edge of ‘discourse, speech or civilisation’.

On the edge of fashion: Arlette, Alfa Bransfield, Aaron Ford, Jonah Pontzer and Mary Stephenson continues until the 25 Feb 2023 at Rose Easton, 223 Cambridge Heath Road London, E2 0EL.

Find out more: roseeaston.com / @roseeaston223