Edward Munch, very much a painter, is easily Norway’s most famous artist, and a new 13-floor building – ‘Munch’ as it is styled – was recently opened in his honour. Walking around Oslo, though, it would be easy to think that sculpture is the national preference: statues dot the streets and I visited four sculpture parks. For example:

Monica Bonvicini: ‘She Lies’ 2010. The Italian’s permanent installation of steel and glass, prominent in the aerial view from the top of Munch’s, shifts with the tides. Her three dimensional interpretation of ‘The Sea of Ice’, 1823-24, refers back to how Caspar David Friedrich’s represents the power and magnificence of the north, while suggesting both a ship and an iceberg – as if some freak of global warming has brought one into the harbour. Bonvicini sees it as symbolising change by standing for ‘a permanent state of erection/construction’, which I guess played more directly before Munch was finished.

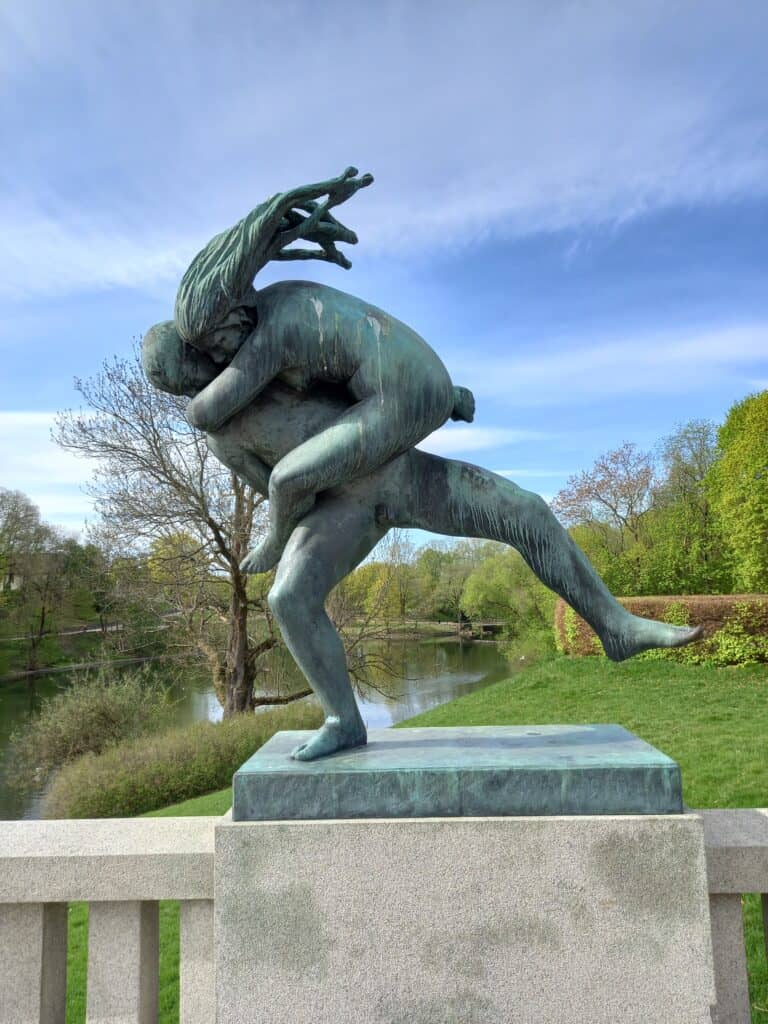

The Vigeland Park (top and above) contains over 600 somewhat Rodinesque figures spread across 192 sculptures, modelled in full greater-than-life size without assistants, then passed to artisans to carve in granite or cast in bronze. Gustav Vigeland is good at the active coming-together of figures with each other or animals or – in his most original move – trees. It’s a popular attraction, even though he missed the chance to apply his skills to sexual interaction…

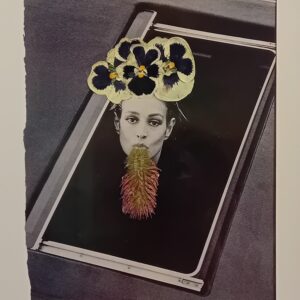

Ann-Sofi Siden: ‘Fideicommissum’ 2000. This self-portrait strikes an oppositional note in the Ekeberg Sculpture Park, which overlooks the city and contains many statues of women made by men. As she crouches to gain relief, a stream of liquid emerges every few minutes. I assume it’s water, but what Siden is implicitly pissing on – according to the title – is the Scandinavian equivalent of the rule of primogeniture.

Art writer and curator Paul Carey-Kent sees a lot of shows: we asked him to jot down whatever came into his head