The Royal Academy’s ‘Man and Beast’ offers the chance to see many prime paintings by Bacon, which is probably all you need to know to book a ticket. It’s about a third animals and two thirds humans as animals – for ‘we’re all animals’, as Bacon liked to say – and 100% bracing nihilism. There are no horses (did Bacon never paint a horse, despite growing up with them?) but plenty of typical Bacon tropes – screaming mouths, cuboid cages, blurred and distorted bodies… I found myself looking at his shadows more than I had before:

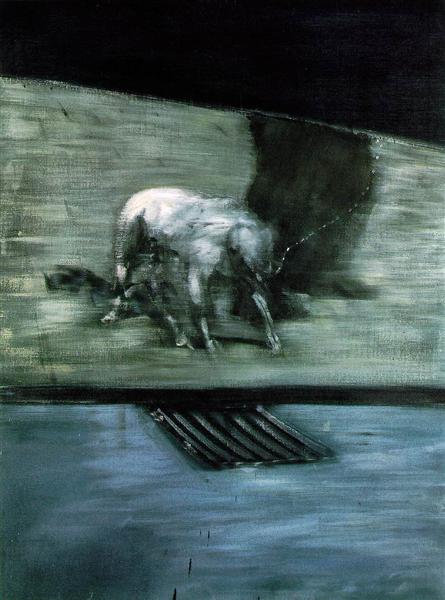

The man as shadow: the owner, one assumes, of the snarling canine in ‘Man with a Dog’, 1953, has been reduced to just a shadow of himself. No wonder the dog seems drawn to the underworld beneath the drain.

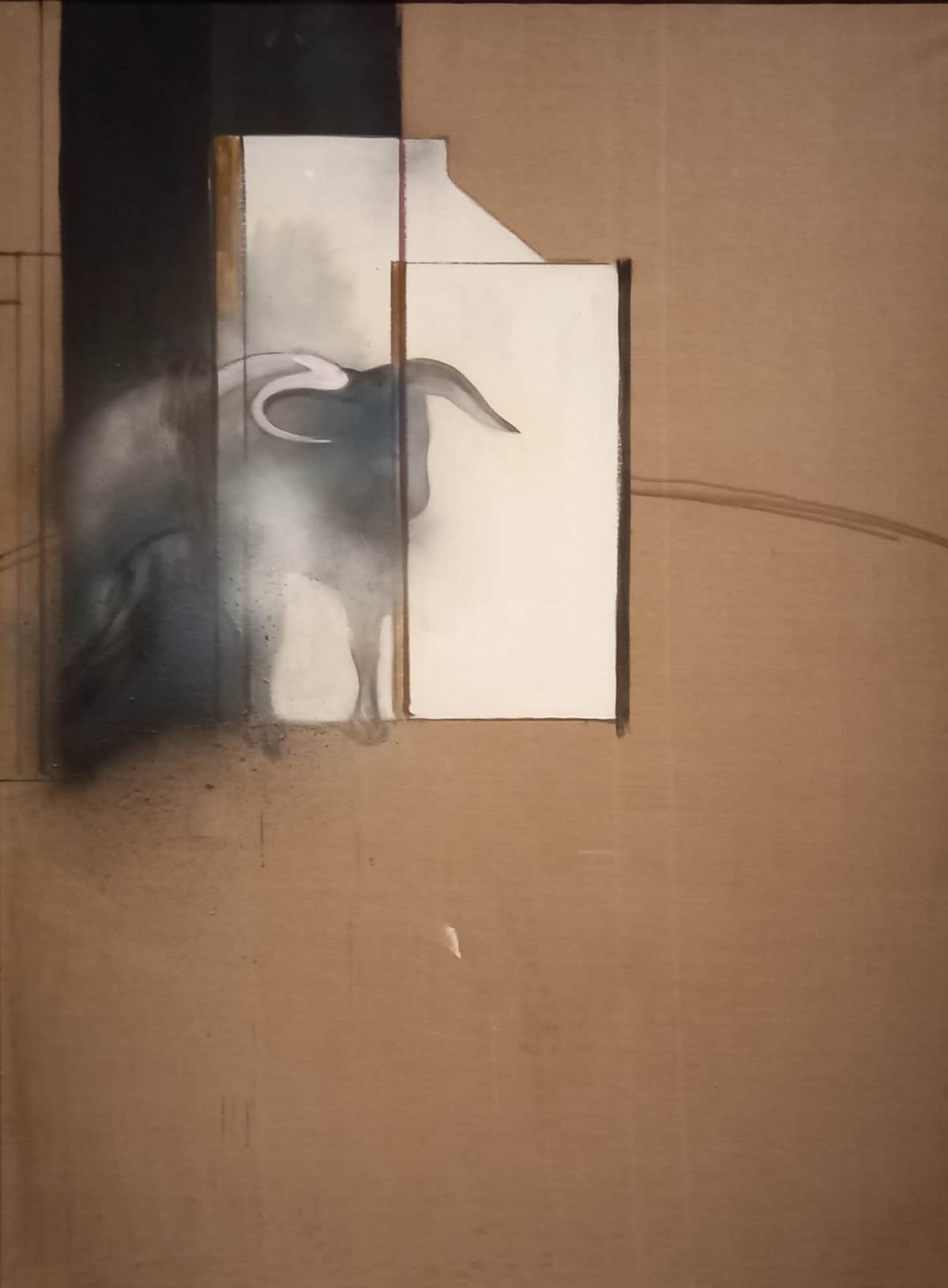

The shadowed splat: Bacon liked to fling a loaded brush at the canvas to introduce the drama of chance. We might read it as ejaculatory, which also makes sense as Bacon declared bullfighting ‘a marvellous aperitif to sex’. In this prominent example the ‘accidental’ mark is emphasised by the addition of a shadow (‘Second Version of Study for a Bullfight No. 1’, 1969).

The flesh shadow: following on from George Dyer’s death, the shadows in Bacon’s paintings of his late lover feature pools of pink, as if his body is melting into the shadows. These are from ‘Triptych, August 1972’ (above and top image).

The shadow of death: perhaps death is implied by every shadow, especially in Bacon, given his obsession with mortality. His last-ever painting, ‘Study of a Bull’, 1991, makes this explicit by texturing the dark with dust.

Art writer and curator Paul Carey-Kent sees a lot of shows: we asked him to jot down whatever came into his head