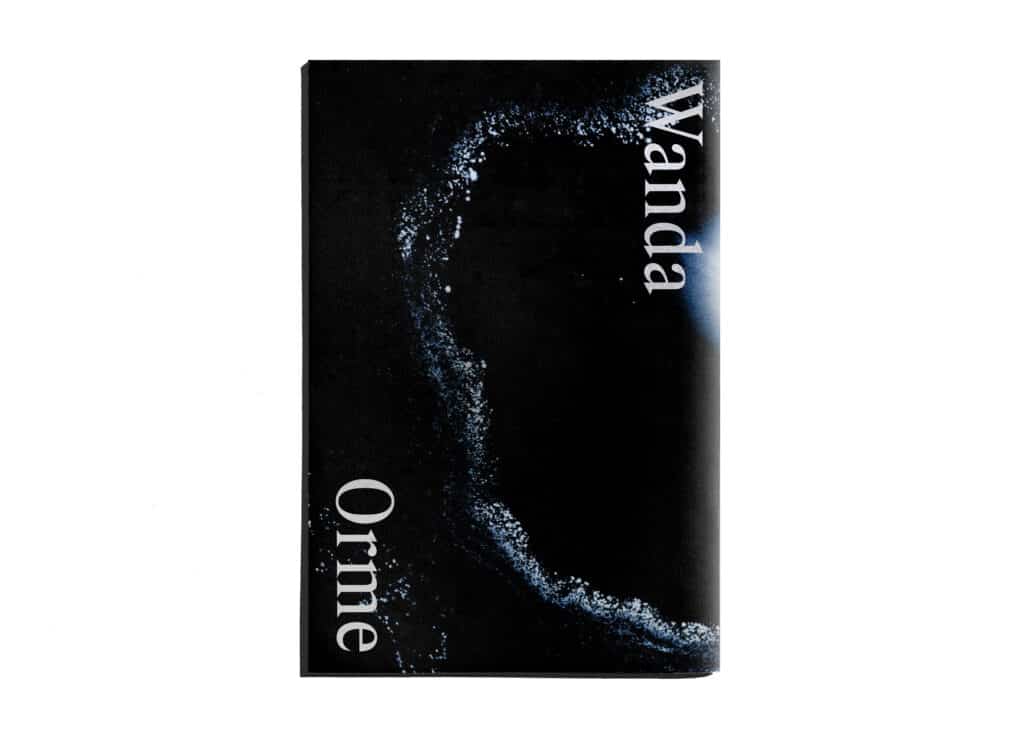

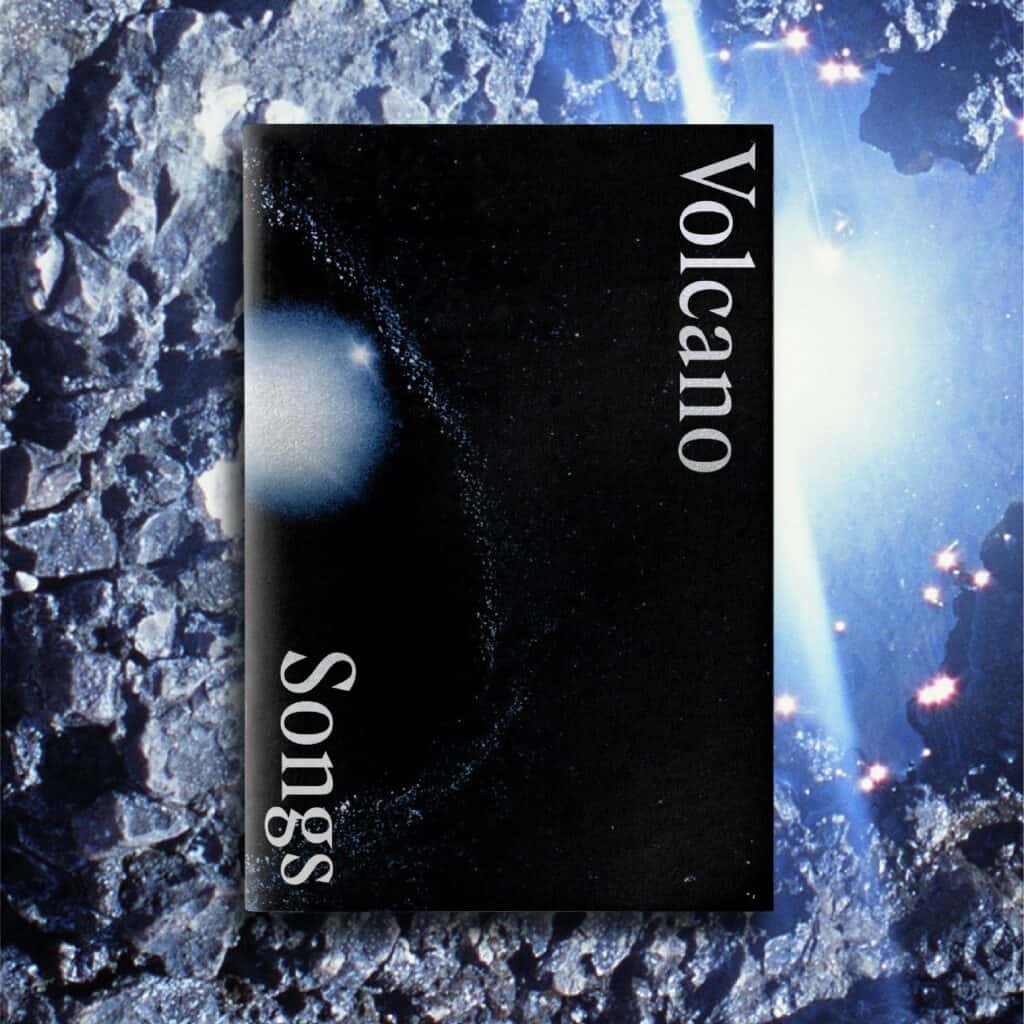

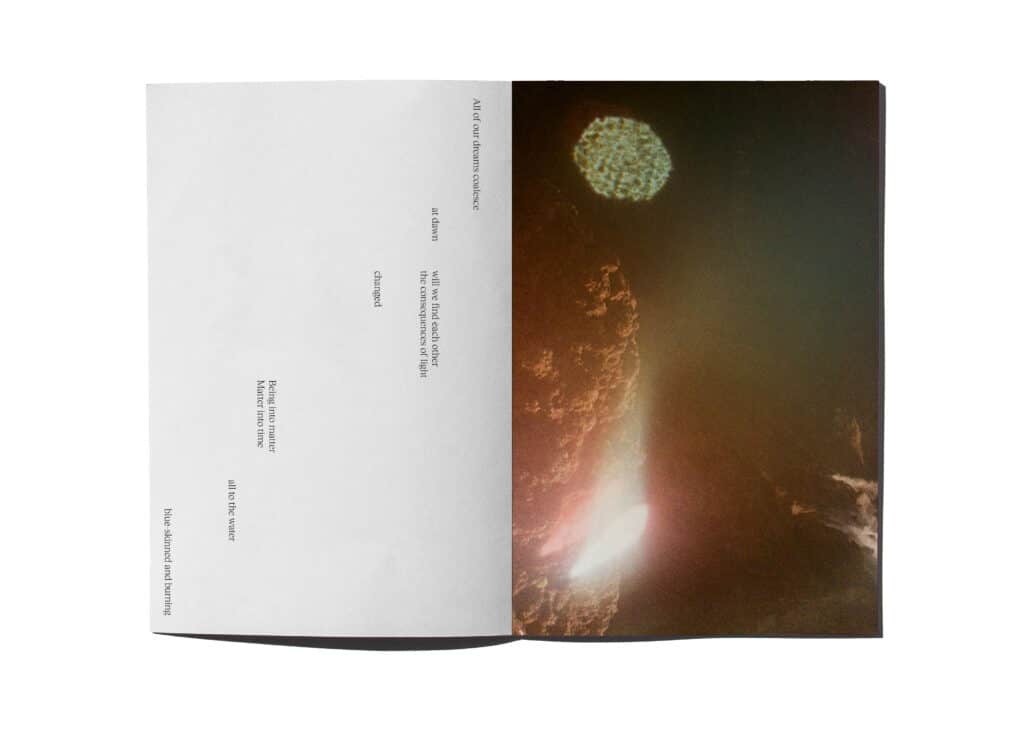

Wanda Orme’s beautiful new book of poetry and photography, Volcano Songs, offers an emotive exploration of the ineffable energy of volcanos. It captures the sensuality and the power of these unique landscapes, informed by Orme’s academic background in both anthropology and psychology alongside a prestigious career as a multi-disciplinary artist and writer. The book was forged in the shadows of Mount Vesuvius and on the volcanic islands of Alicudi and Pantelleria. The moving text, through which the volcano indeed seems to sing, is complimented by images that ground it in the substantiality of the volcano. The visual and written stories co-exist and present an interwoven account that invites the reader to take a new perspective on ecology and geology.

Talking to Orme is a unique experience, as unlike many people I have met, she chooses her words with absolute precision. As a writer who navigates the almost ineffable, this is hardly surprising yet consistently refreshing. When she speaks of Mount Vesuvius and her experiences writing the book, I am awash with a sense of calm and a heartfelt reminder to seek out natural places of beauty. She postulates that the truest sense of belonging can be found through cultivating real relationships with the natural world and tuning into the energy and presence that certain places offer. After reading Volcano Songs, it becomes difficult to disagree with her.

Firstly, would you like to introduce your new book Volcano Songs – where did the idea come from for this?

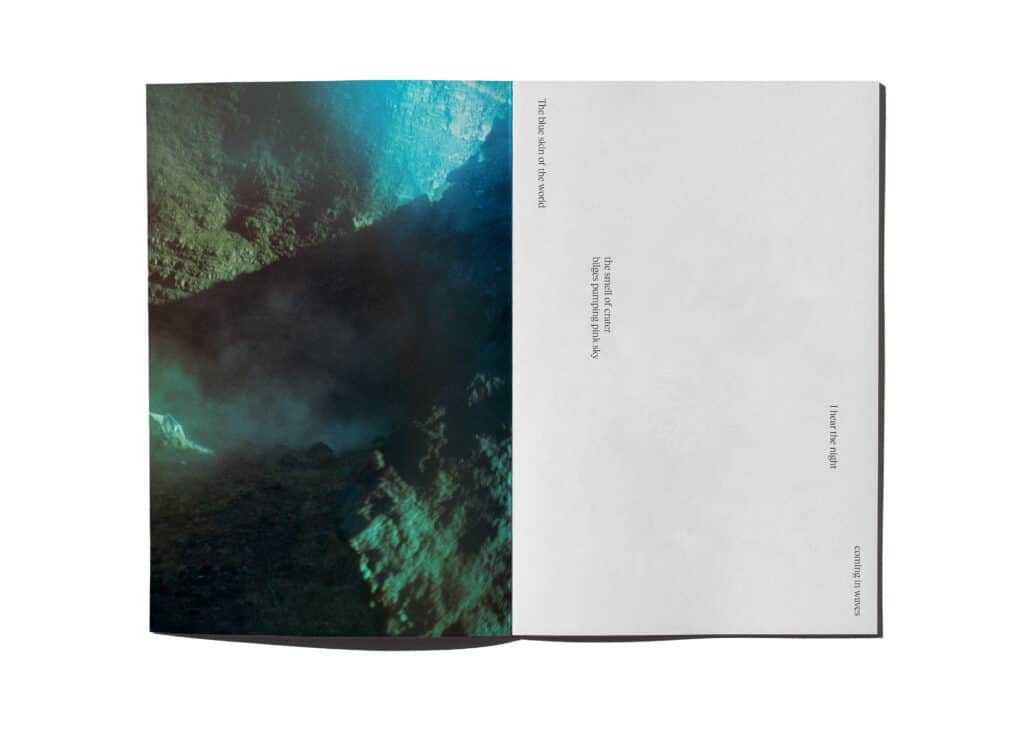

Moving to Naples, I lived in a city dominated by two very powerful natural features, the sea and the volcano, Mount Vesuvius. These presences change you, I began to orientate myself in relation to them. The volcano dominates the landscape and one becomes keenly aware of its presence, even when it is not visible. I felt a sense of the moving geology around me, rippling between things – as if there were a constant conversation going on. A sense of power also became central to the work because there is a humility and an audacity which comes with living on the slopes of a Volcano. A different kind of power than the human-constructed notions of power that we often associate with the term.

What was your experience of making the book? Where did you start and what steps did you take along the way that led to its creation?

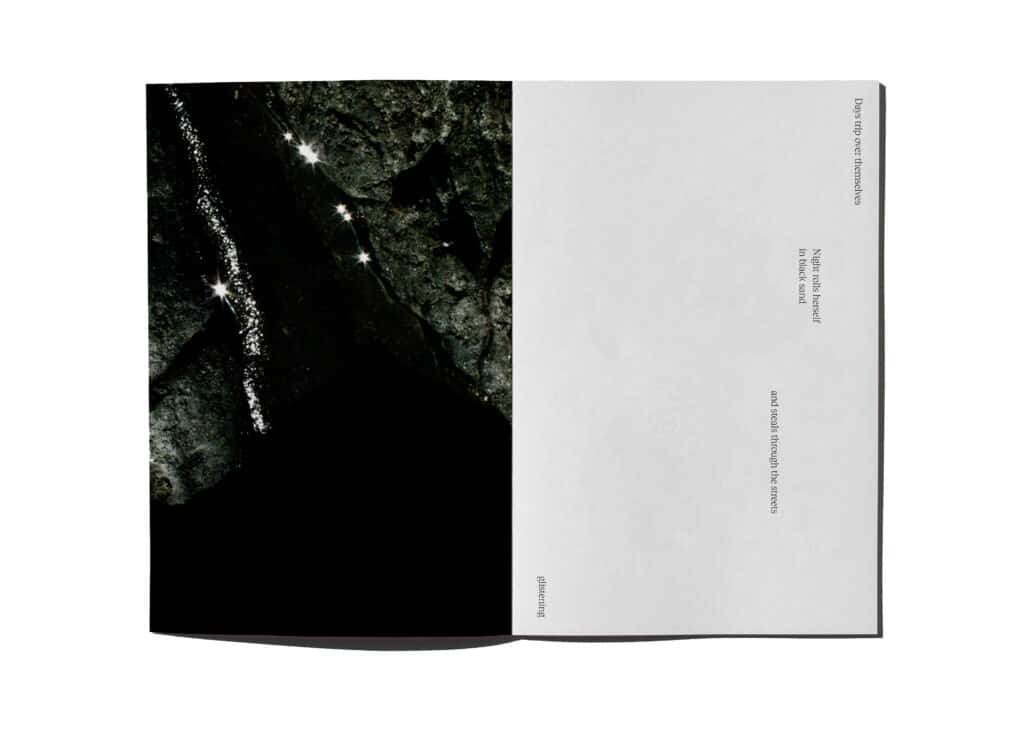

I wrote much of the text on an Island called Alicudi, off the coast of Sicily. It is an extinct Volcano, and it has a very interesting presence. Throughout the book, there is this sense of an energy. Unlike Stromboli, which was erupting next door, Alicudi is quiet and still but you can somehow still feel that it once was active.

Some of the photography fed in naturally, I went to shoot the crater of Vesuvius which was an incredible experience because it felt so animate. Like an animal that I could relate to as an animal. You expect a volcano to be very otherworldly, but actually it felt incredibly of this earth and alive. They breathe, they respire, they exist like a body

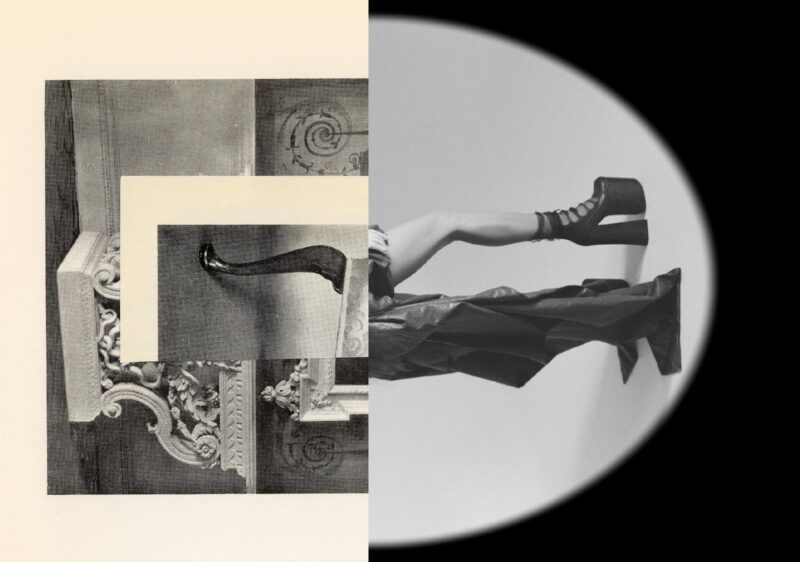

This book presents beautiful, textured photography alongside lyrical poetic writing. Did you create these elements simultaneously or did one come after the other?

The combination of text and photography came about quite naturally. Initially, I wrote the text all in a notebook during a short period of a few days. The photography came afterwards. Previously I have had concerns about bringing together poetry and imagery as I don’t want to repeat the same idea or let the words feel like a caption. But it started to feel as though the photography was a necessary element, as a part of the conversation, like parallel interweaving narratives. I really wanted to bring in the substantiality of matter. The words could be understood as quite ethereal or transient by themselves, I wanted something to root it in the terrain, the heat, and the earth of the place itself. I wanted it to have an element of the non-human beyond words as a human construct. To be grounded in the thing that refuses to be neatly contained, the volcano.

When taking images for this project, what kind of equipment did you use?

I used a camera that I have used for so many projects, which is an old OM10 that my mother gave me. I deviate from using this camera every now and again, but I always go back to it. There is something about it that adds weight to the process. I like the fact that it shakes a little when the shutter goes. It has a sense of being an almost living thing, and it doesn’t always co-operate. It’s another part of the conversation between myself and the world.

It seems like objects that speak back really resonate with you. In your practice there isn’t a sense of domination through investigation, instead it’s a shared conversation between yourself and that which you’re studying and attending to through creation. Would you say your work shares a symbiotic relationship with the subject matter?

I think I could aspire to that. I don’t know what I can genuinely say that I give back to a volcano, but I’m definitely trying to give something to the people who engage with the work. I think I could say that I hope to show the volcano the humility and care that it deserves as a subject.

I think a question of hierarchy and bringing your own vulnerability to the things you do is important. I don’t want to replicate myself through my work, although we are all doomed to do that to some extent. I hope that I’m learning as I work and that therefore the work shows something of the object that I’m trying to attend to. I’m aiming to avoid creating an endless repetition of my ideas and seeking to be changed through the experience of making.

Are there any particular sources that you found really inspirational for this project beyond the natural environment itself, perhaps books you read or artworks you have seen recently?

Definitely, I read a lot. Today I was reading Cormac McCarthy’s Cities of the Plain, in which a boy adopts a wolf which he eventually must kill, it’s very sad overall. There are parts of this book about an inaccessible but occasionally glimpsable mysterious, massive, and powerful beyond that we exist in but, for the most part, are completely unaware of. I like writers that encouraged me to have confidence in that belief, that feeling of something more because systemically we’re taught to unlearn this kind of spiritual connection to otherness and sense of instinct.

I find inspiration in work by everyone from photographers and film makers to painters and poets. I love Anne Carson. She’s one of the first writers I discovered that was talking about the difficult, the uncomfortable and the in-between.

Fundamentally, waking up and going to sleep every day seeing Vesuvius changed me. It felt like an animate, characterful being had come into my life and was so present. And yet, the book is also about something more, it’s not entirely about the volcano at all, but about the kind of energy that is manifest in volcanos. The energy that runs through and between the environment, the water, the people living with it. The book is about something slippery, there’s a kind of hide and seek with an entity that remains slightly intangible.

You’re attempting to discuss things that are quite ineffable, it’s slippery and intangible because you’re trying to capture that which refuses to be neatly packaged. It’s like trying to explain the ocean to someone who has never seen it. I think, through and in-between the words, maybe people get a sense of what it might be like to spend time near a Volcano.

In the spaces between the words, or in the resonance when you finish a sentence – that moment when a feeling has been conjured and it lingers. Maybe that’s more the point than the words themselves.

There’s something you wrote in the book about the impact of Volcanos, that “they remind us that the planet is not ours”. When I read that sentence, to me it really felt like the crux of what you are exploring. What does this mean to you? Is it a kind of advice or a reminder?

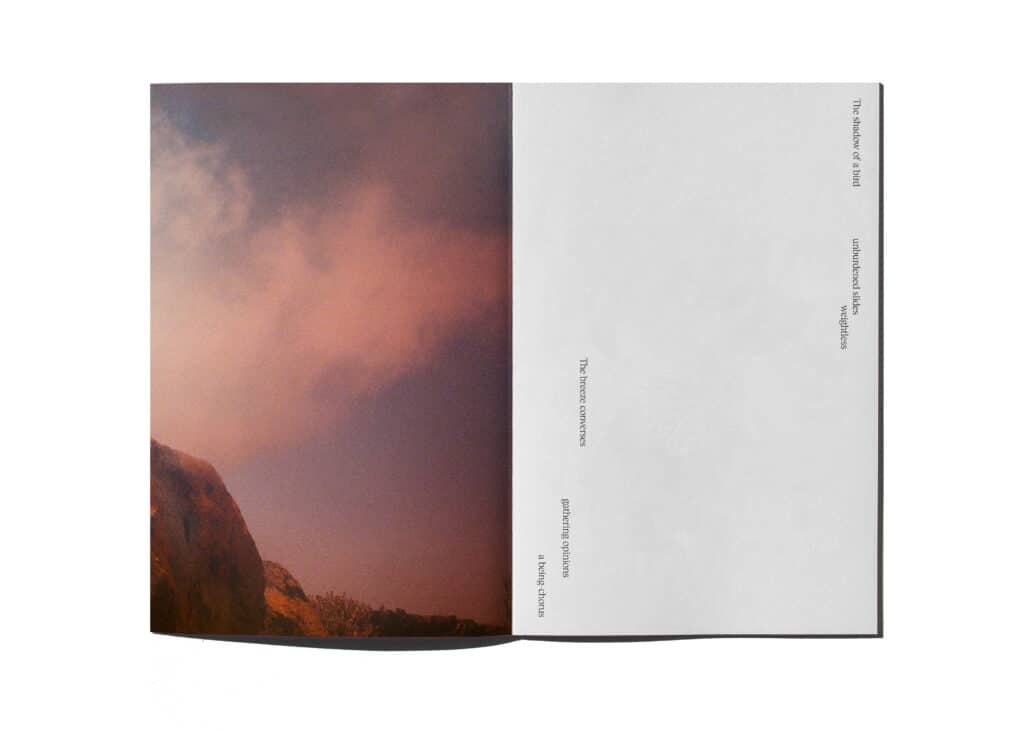

It’s advice and therapy. I think people are collectively missing a great sense of belonging which would come through an acknowledgement of the fact that we belong to this earth; we come from it, we return to it. We are borrowed matter assembled temporarily into a form that we think of as ourselves, which eventually gets recycled. The great state of modern angst, feeling alone and disconnected, could be changed by shifting our relationship to the earth as one of belonging. In the contemporary moment, we are in a war of attention, and we very rarely get the opportunity to ask ourselves where we really feel good. I think if we stopped and listened to ourselves, we would change the way we care for the environment and the way we prioritize and attribute value to things. The way we ascribe power, and what and who we revere.

So you’re saying if we learn that we belong to the planet, rather than understanding it as belonging to us, ultimately we would be happier and more fulfilled.

I think there’s a reason why concepts like ‘mother nature’ have existed for as long as they have, because there is truth to them. A sense that we come from the earth. From this understanding, we can have a sense of being held by something, of connection and belonging. It’s thinking about identity beyond a human framework. A more grounded understanding of what it means to be human in relation to nature, and an acknowledgement of the power of nature. I think there is so much joy in standing at the edge of the sea and feeling accepted and unacknowledged at the same time. This huge thing is indifferent to you while also allowing you to be part of it. I don’t know quite how to put it into words but it’s powerful and magical. We should be encouraged to follow those kinds of feelings more.

Is there a kind of take away from the book, perhaps a message or a feeling you particularly want to convey?

The feeling of being a part of something powerful. Finding that feeling really changes people. Imagine knowing that you belonged before you’d ever even wondered about it.

Purchase Volcano Songs by Wanda Orme via Guest Editions: www.guesteditions.com

Learn more about Wanda Orme @wandaorme or www.wandaorme.com