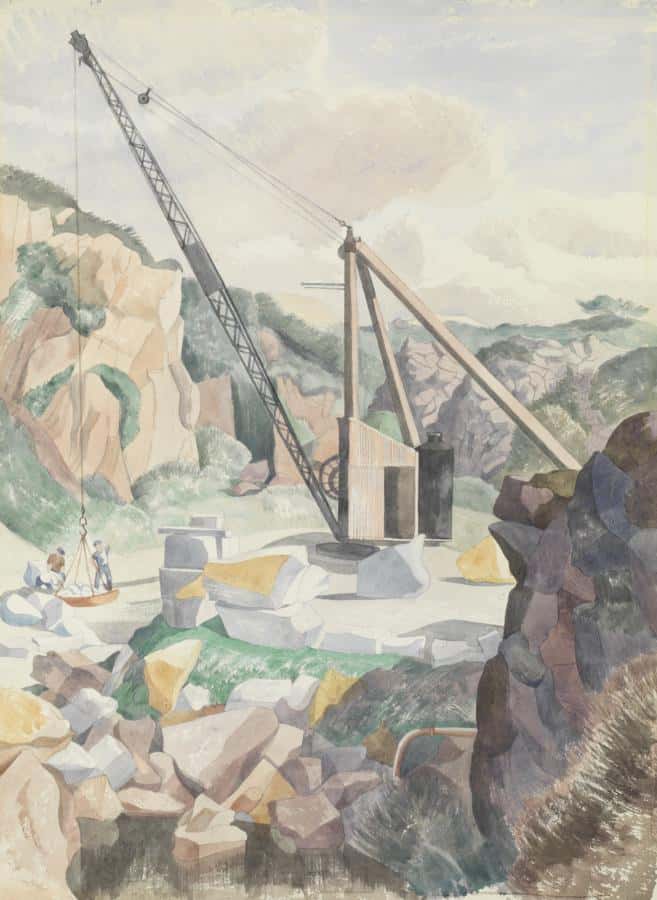

John Nash: The DeLank Quarry, Cornwall, 1963

John Nash (1893-1977) tends to be remembered as the less radical younger brother of Paul, a first rank illustrator as well as a longstanding Royal Academician adept at the subtle transfiguration of landscapes, particularly in watercolour. He was also an artist in both World Wars, albeit both less famous for that than Paul and less favoured by circumstances: for example, as a private rather than an officer in World War I, he wasn’t allowed to make any drawings while at the front. Those impressions are confirmed by the comprehensive retrospective you can now see at the Towner Art Gallery in Eastbourne (to 26 Sept). It’s an enjoyable show, with small surprises in his early cartoon work, and in just how good his botanical engravings were. One wall label, however, mentions that he and his wife were on holiday ‘with their lovers’. The exhibition says no more, but a recent biography by Andy Friend reveals that Nash’s private life was much less conservative than his art.

John Nash with Christine Kuhlenthal, 1918

When he and Christine Kuhlenthal (1895-1976) married in 1918, they both had interests in other women, and agreed that theirs would be an open marriage. They seemed to have maintained that principle energetically over most of the following 58 years together: Christine with lovers of both sexes, John with women who seem to split into two types – mostly the wives of other artist colleagues, whom she accepted as ‘old steadies’, but also occasional dalliances with younger ‘Dolls’, as Christine termed them. It would be nice to report that this all went swimmingly, but Friend reports that Christine suffered a good deal of pain and jealousy, particularly when a ‘Doll’ was involved, both for herself and because she felt that those affairs made John miserable. ‘An odd thing, this sexual attraction’, she’s recorded as saying of one affair: ‘The only comfort is that it passes and when it goes there won’t be much left’. We don’t hear what John thought, presumably because there are no records of that. But we do also read about the tragedy which struck the couple in 1935, when their only child William, then four, died when he fell out of the door of the car Christine was driving. Add the wars and a mother who was committed to a mental hospital for most of his childhood, and it may not be a surprise that Nash suffered from depression. All in all, then, there’s a good deal going on behind the well-ordered surfaces of Nash’s paintings.

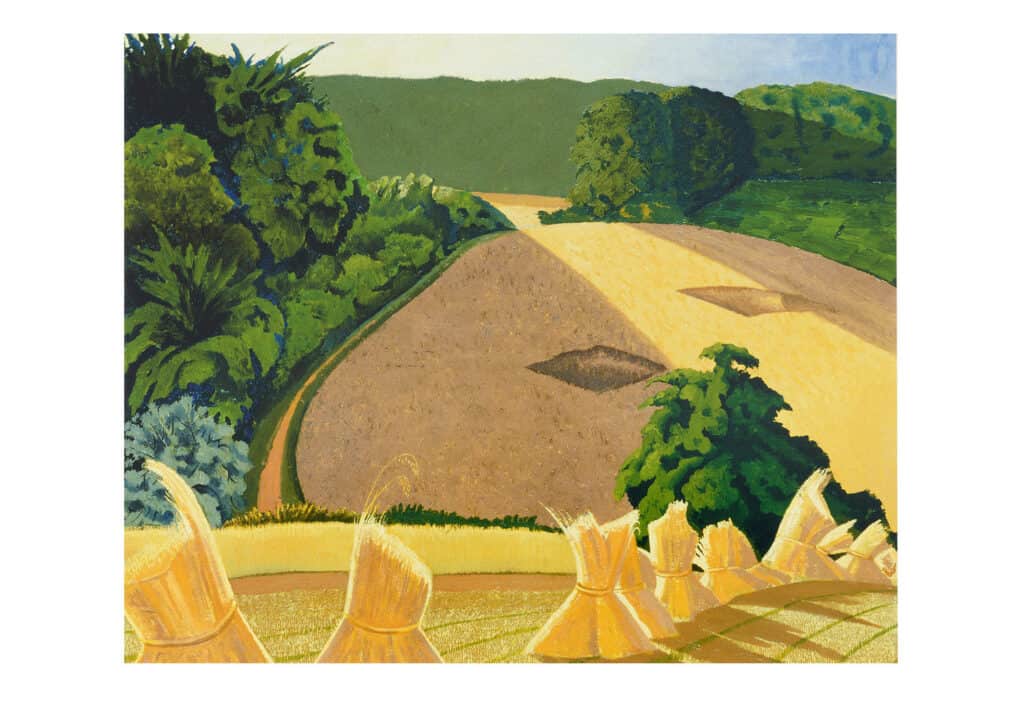

John Nash: The Cornfield, 1918

* Andy Friend: John Nash: The Landscape of Love and Solace (Towner Gallery / Thames & Hudson, 2020 – 352 pages)

Art writer and curator Paul Carey-Kent sees a lot of shows: we asked him to jot down whatever came into his head