To die for

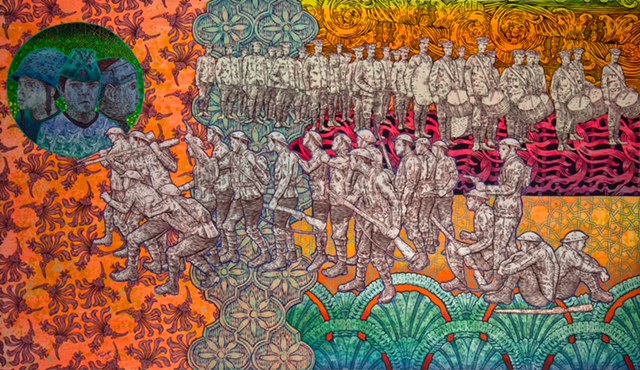

Is there really something that is worth dying for? People have historically been manipulated to die for ideas. The conviction and dedication of the people who offered their lives were real and praiseworthy, even if the reasoning behind it wasn’t as worthy of admiration.

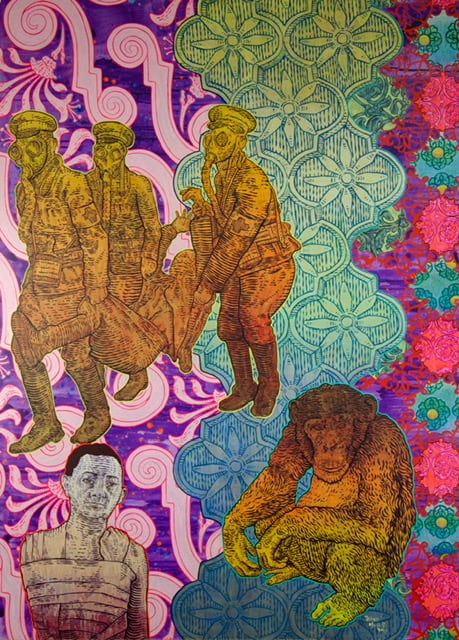

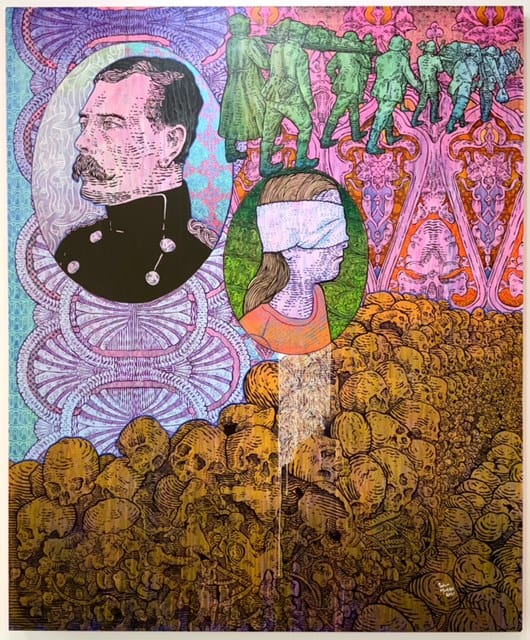

Our founding myths are based on the sacrifices that people made—those ideas that apparently were worth dying for. Maybe there are things worth giving your life for. This is what I want you, the viewer of my artwork, to ask yourself. In the time of the pandemic, where so much strife and death is around us, maybe it’s time to ask what is worth dying for? I have made this series of work with the idea in mind that there are people out there who have incentives to exploit you into dying for them, hiding behind ideology. The great empires of the past and present, especially the British empire, have created their holy saints. I call them the saints of power, like Lord Kitchener, who was celebrated like a minor deity, or the Soviet saint we know as Lenin who is revered to this day. These figures inhabit my work and are visual representations of entire ways of thinking.

We are one amongst the thousands of species sharing a single biosphere. It is important to keep in mind how close our next of kin are, the chimpanzee, the gorilla and the orang-utan, and that we have hunted them to the ends of the earth. I use them in my work to remind myself of my place in the universe. We are all just apes finding our way, stumbling in the dark. The blind leading the blind.

The pandemic has exposed how vulnerable we are, and how little we may actually understand about anything. The authorities lied so many times about so many things, leaving many people like me in a state of absolute disillusionment. I make artwork to deal with the discord and apprehension I feel about the narratives and myths that have formed the basis of our history and that dictate our future. Sometimes I create artwork that resembles government plaques or emblems, which traditionally symbolise the power of the authority or king, but in my artwork are the insignia for the disillusioned.

I also wanted to show how we are just material things made from stardust. I was looking at ways to express that idea visually and I came up with the idea to make work out of human ash. Human ash is a very grainy material. It has a strange look and feel to it, a unique way that it reflects light. I used the ashes of a few people given to me by friends and family mixed together, so as not to be a shrine to a single person. The use of human ash is more of a reminder of what and where we are in this universe and is something grotesque made beautiful. The use of human remains in artwork has a long history. There was a pigment called mummy brown used in Victorian times that was made by grinding down mummies and mixing the material with oil. Obviously, the attitude towards human remains has changed over time. We don’t grind up historical artefacts to make pigments anymore.

Despite a feeling of disillusionment, as we start to emerge from the pandemic, I find myself very optimistic about the future. I use imagery of bandages and wrappings in my work to express this sentiment. Symbols have a multitude of interpretations—this is the beauty of a symbolic language such as hieroglyphics. Many different ideas can be presented at the same time depending on what symbols are used together.I first started using the imagery of wrappings and bandages during my time in Egypt in 2018 and came across animal mummies in the museum at Cairo. These mummies represented a fascinating visual metaphor of something truly ancient, a piece of organic matter wrapped up in an artistic manner that was preserved over the ages. The original significance has now been lost, but these had at the time a very real and profound meaning, which was understood by almost everyone in ancient Egyptian society.

The bandages are metaphors for progress or healing, but at the same time, it’s as if there is something to hide, an ugly thing under a bandage a truth of our being, and the reality of what it means to be alive.

Bandages are usually applied by experts and trained professionals. When one sees a bandaged individual you can deduce that the bandaged person has just been to some sort of medical professional. This idea is something I was playing around with before the pandemic but has become more prescient since.

I want to leave you with one idea, and it’s something humbling and awe-inspiring—I hope my work can convey the idea that nobody is at the centre of the universe. It’s the Copernican principle that we are in no way in a special or privileged position and that nothing about this time or place is extraordinary. Nobody has the answers. We are all just fumbling in the dark, and you just need to find out for yourself. Ask yourself, what is worth dying for?

New drawings, paintings and sculptures made during lockdown by Peter Mammes TO DIE FOR from 18th to 21st August At Noho studios, 46 Great Titchfield Street, London. www.patterndiscord.com

© Peter Mammes