I first met Julie Umerle at an artist talk that accompanied her solo exhibition ‘Rewind’ at the Bermondsey Project Space in 2016. I was immediately taken in by the calm confidence both the artist and her abstract paintings convey. Her practice has gone from strength to strength since with museum shows as far afield as Poland, the USA and China, as well as prestigious collaborations including Deutsche Bank at Frieze and an artist residency with Marriott Hotels.

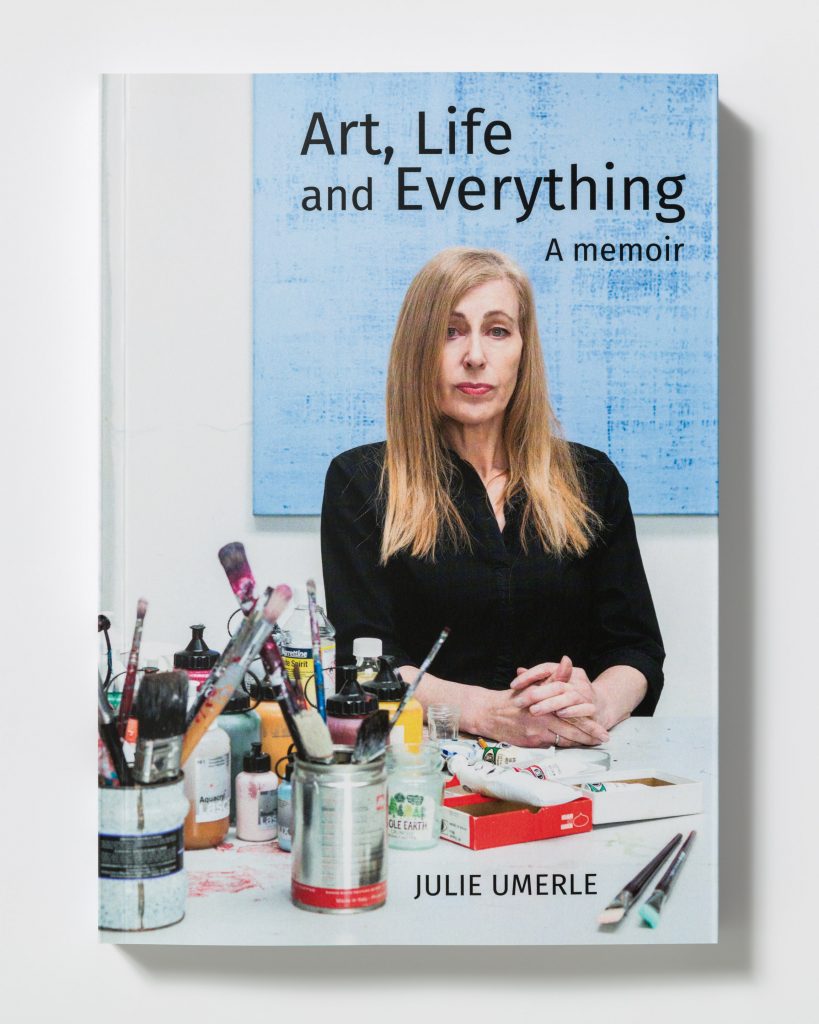

‘Art, Life and Everything’ was published towards the end of 2018 and I first read it over the Christmas holidays. The term memoir started taking on real meaning as reading about Umerle’s memories brought back so many of my own, as she weaves her personal story around global events like the fall of the Berlin Wall, life before and after 9/11, or London specific memories of the Kings Cross Fire or the suicide bombs of July 2005, highlighting just how much the world has changed in the relatively short period of the three decades covered in the book. Our paths could have crossed any number of times, at dodgy squats in 80s London, one of many Nick Cave gigs or at ground breaking Brit Art exhibitions hailing the emergence of a new art establishment in the 90s.

London and New York are the backdrop to Julie Umerle’s story and I loved being taken back in time; wishing I had experienced a more bohemian Notting Hill to witness her first exhibition there in 1980, or fulfilled the dream of living in downtown Manhattan in the 90s – I was a lot less courageous than Umerle who arrived in New York on a one-way ticket determined to stay until money ran out. I’ve enjoyed reading her assessment of the cultural differences between both cities; insights into an unconventional family life, personal highs and lows and everything in between, are all told with subtle humour and without sentimental nostalgia.

I re-read the book during the first lockdown to remind myself that selective self-isolating during a global pandemic is easy compared to experiencing serious surgeries in true isolation and hooked up to a ventilator (I have a much better understanding now of exactly how gruesome this is). Accounts of her spinal operations in 1984 and 2004 are major time markers in Julie Umerle’s story so far, with the trauma of the latter undoubtedly a chief motivation for the book.

References to early feminist writing, in particular the notion of the personal being political, are even more relevant in our hashtagged times of #metoo and #blacklivesmatter; and while Umerle’s abstract paintings are not political at first sight, succeeding as a disabled woman against many odds and obstacles could be interpreted as a political statement of defiance against a world where everyone who appears different continues to be stigmatised.

Julie Umerle’s identity is defined by being an artist before being disabled and, above all, ‘Art, Life and Everything’ is an account of what it takes to be an artist. I recommend the book to anyone whose creative practice lacks motivation or direction due to current inhospitable conditions. Umerle’s story is one of creativity and self-expression conquering even the most chaotic circumstances.

While many believe that an artist’s career should be linear from graduation to being discovered and culminating in a museum retrospective, real life is a lot less predictable. The art world moves in cycles and artists are generally the first to suffer in a recession. Umerle’s memories of cancelled projects and struggling galleries in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crash are not dissimilar to what we are witnessing now.

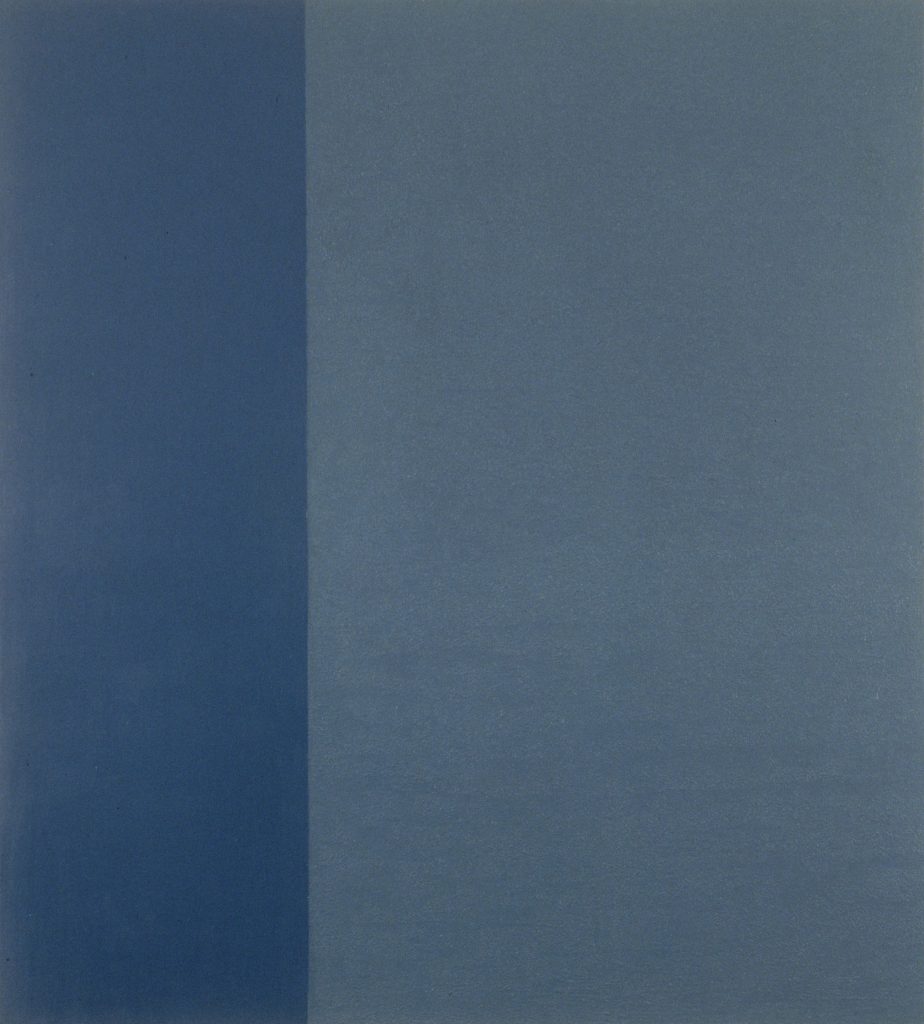

Her career progressed steadily for ten years from the alternative scene and showing at non-profit venues to gaining mainstream recognition with a solo exhibition at the Barbican. Returning to full-time education and moving from London to New York as a mid-career artist meant leaving history and context of her work behind and to start all over again. With New York an important place in the development of abstraction the move was an essential step to explore the historical and philosophical framework of her practice, which follows in the tradition of American artists like Barnett Newman, Agnes Martin or Robert Ryman.

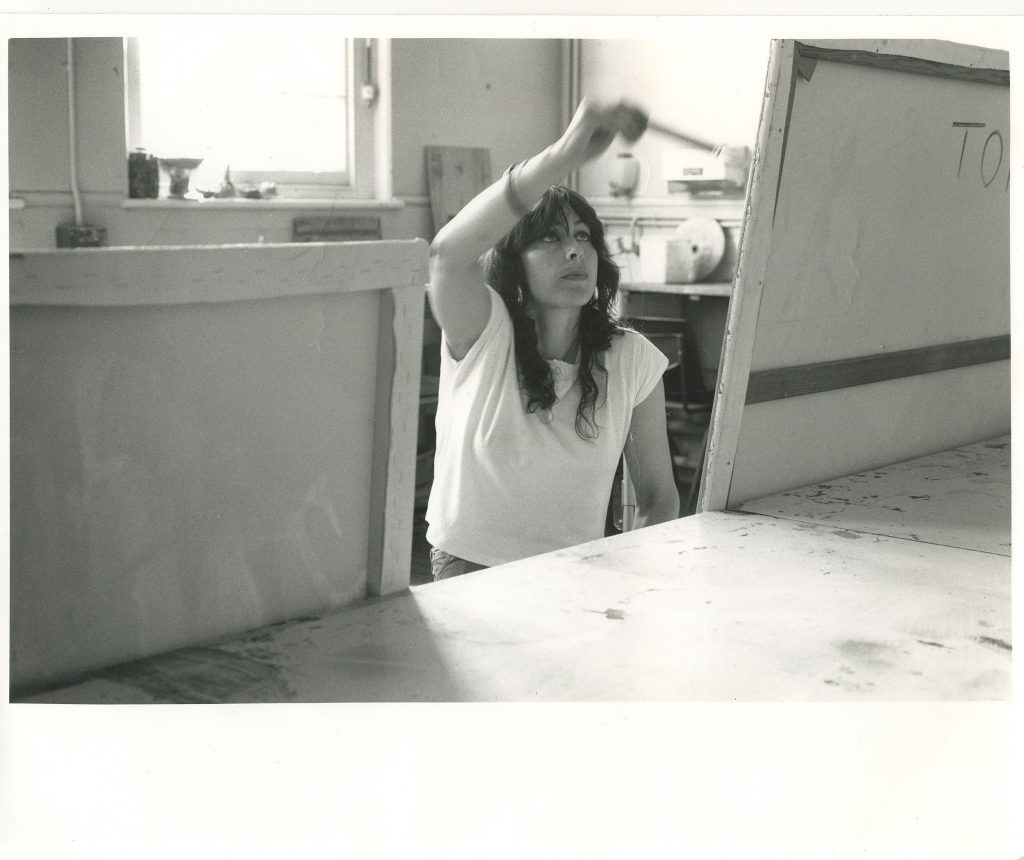

Undisturbed periods of concentrating on developing one’s practice without the pressure of seeking out exhibition opportunities are essential for artists to gain confidence and purpose. This is where government grants and funded residencies play an important part. While the latter are often inaccessible to disabled artists, successful grant applications have been fundamental in Umerle’s development beyond the obvious benefit of providing time to develop new work and the prospect of future sales.

The author is generous with sharing her thoughts on running a successful practice; from the importance of record keeping and documenting work; on building up a professional support network of art suppliers, photographers and framers; the significance of critical reviews and exchanges with other artists; and on developing a wider circle of contacts as very few breakthroughs are due to pure chance. Umerle’s accounts make for inspiring reading and provide relatable context many guidebooks for artists are lacking.

Studio visits are often the first step to gallery interest and are very likely to result from introductions through third persons. Some exciting examples of people along Umerle’s journey and how they are connected wind through the book. She observes that recognition does not come from working in the studio and hoping to be discovered and has more to do with who sees the paintings when they are out in the world, and where they are shown.

The book is full of lived examples of how an artist’s environment is reflected in their work, from a practical level by adapting canvas size and materials to financial and spacial constraints; of careers developing at a different pace whether working in London’s industrial estates or to a backdrop of glamour and glitz at the heart of New York City; of the importance of rituals, whether preparing work for transit or repainting studio walls and floors before settling into a regular studio routine; to external triggers that can influence the work’s direction.

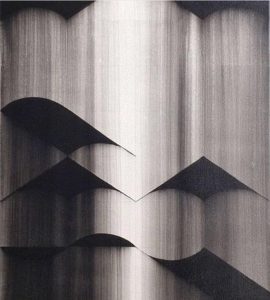

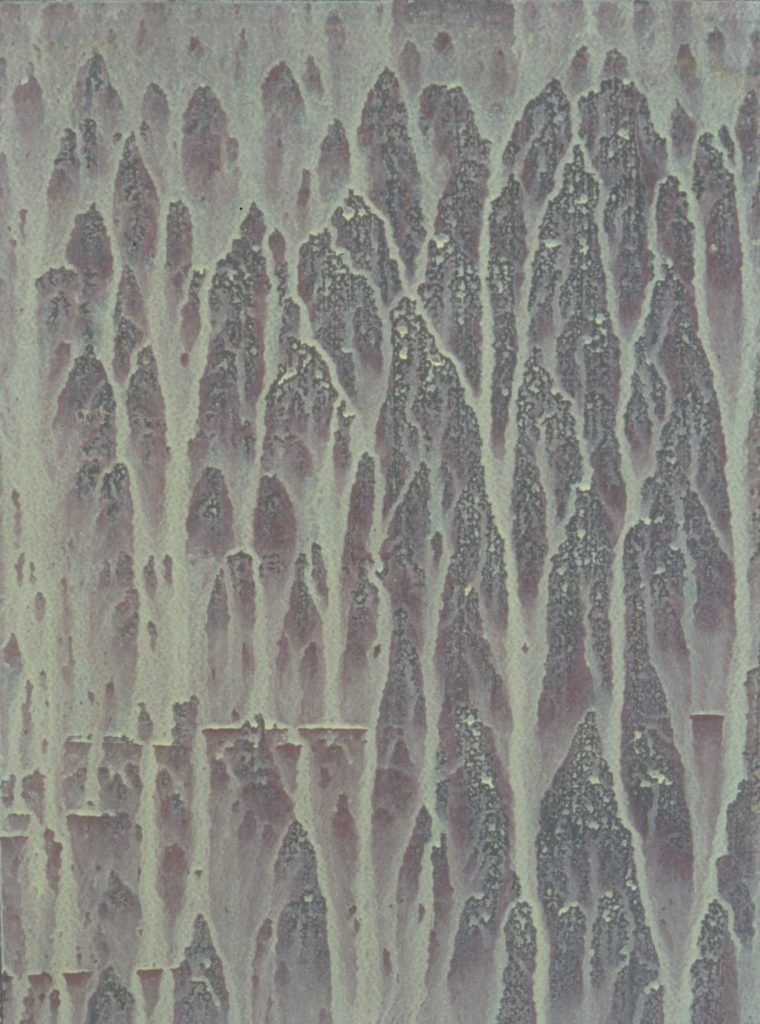

Examples of her paintings are reproduced throughout the book and illustrate the various stages of experimental and process-oriented approaches, of discarding and rediscovering colour, moving from individual paintings to working in series, from untitled to titled works. Abstract art is difficult to describe and I am taking liberty with paraphrasing Saul Ostrow who stated that were these paintings to succeed we should be able to say nothing about them.

Photo credits (in order): Daniel Devlin, Maja Kihlstedt, John Riddy (x2), Peter Abrahams, John Riddy, Maja Kihlstedt

Julie Umerle is an abstract painter who lives and works in London.

website | @julieumerle | Waterstones