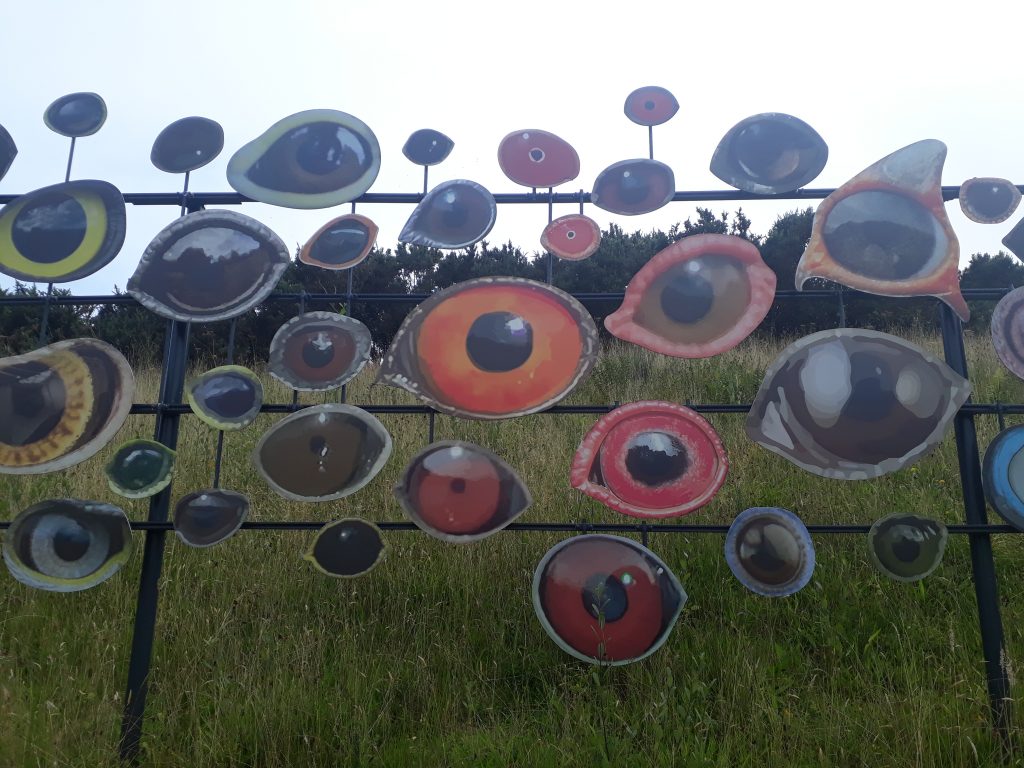

Jenny Kendler: ‘Bird Watching’ 2018-19

I guess no one visits the Eden Project in Cornwall to look at art: to enjoy the plant life, take in the biomes and reflect on environmental sustainability, yes; to zip across the half-mile SkyWire, maybe. But there is an art trail, along with a map identifying sixteen works to see, and I followed it last week. One work I couldn’t find, and two were out of action: Ryan Gander’s edgily playful fountain bust giving visitors the chance to drink from his wife’s mouth was understandably dry for reasons of Covid-19. Nor was Julian Opie’s huge LED of a walking crowd operative, though I assume that was down to a technical issue rather than an illogically zealous interpretation of social distancing rules. On the other hand, there are as many sculptures dotted around the grounds which don’t get on the list: an orangutan by James Wild and various outsized insects, for example. They tend towards the jokily illustrative, but the same could be said of some of the inclusions: David Kemp’s metallic flora punningly titled Industrial Plant, Heather Jansch’s driftwood-based horses and Robert Bradford’s Bombus the Giant Bee. Nor was I much taken by the figures of Peter and Sue Hill and of Tim Shaw, though they worked well as diversions to come across. Still, that left a core of works which struck me as impressive regardless of location, yet which gained from the connections made at Eden and would consequently enrich the experience of all visitors, art lovers or not.

Seven remaining artists may not sound many, but their impact is disproportionate. Indeed, one large building is dedicated to just two huge, cinematically presented works.

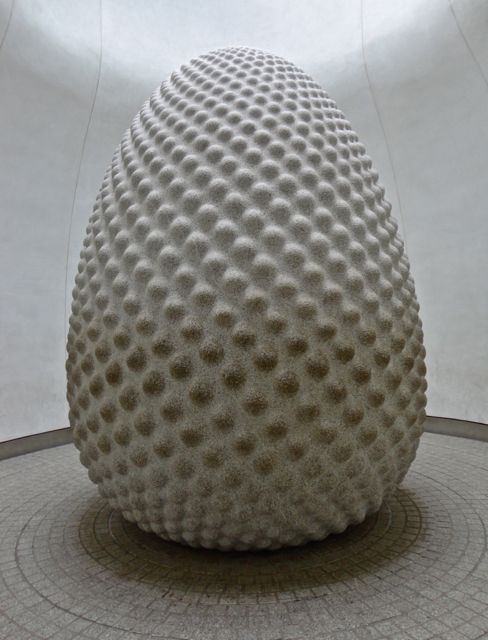

Peter Randall-Page’s 70-tonne granite Seed, 2007, has its own atrium, in which its 1,800 nodules hum gently in their Fibonacci sequencing. That separation saves it from being improbably dwarfed by Studio Swine’s Infinity Blue, 2018, a nine-metre high ceramic representation of the microscopic cyanobacteria – the basis for plants producing oxygen through photosynthesis – which emits vapour to mimic that natural role. It has real presence, as well as educational value, and is an absolute favourite with children.

The rain forest biome also has two worthwhile art stops.

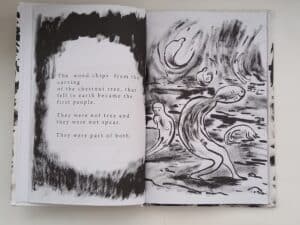

Aziza Gate, 2004, El Anatsui’s characterful group of totem faces formed out of charred timbers from the nearby Falmouth Docks, deftly conjoins narratives of recycling and the history of colonialism. And Peruvian herbalist-artists Don Francisco Montes Shuna and Yolanda Panduro Baneo have made a set of twenty murals on the rock face, showing their versions of tales associated with the plants with which they work (below is ‘The Spirit Woman of Ajo Sacha’, 2001).

Not only are these wittily charming, but they are also very much in tune with the need to allow nature more agency – and the paintings gain from a location which leads many to be occluded by leaves which segue into the images.

My other three favourite works are easily missed. In the absence of any notice (labelling is generally erratic) Chris Drury’s Cloud Chamber, 2002, might be taken for a domed hut by anyone not following the art map. Which it is, but in the meditative spirit of a James Turrell skyspace.

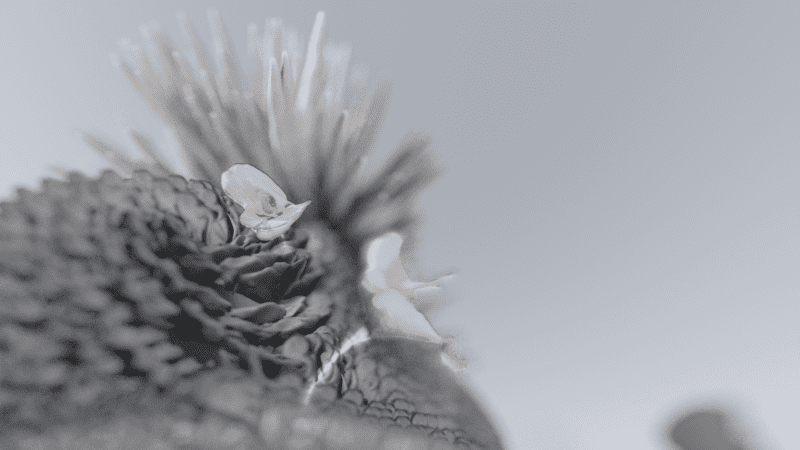

Jenny Bevan’s fifteen Cores, 2016, hide in plain sight at the entrance to the ‘Wild Cornwall’ section: many must have taken them for spindly tree trunks, but they are actually ceramics which impersonate the layering which might occur were they cores lifted from the ground of Eden, with plant life imprinted in the tops and colouration representing the descending geology beneath them. Finally, along the road half a mile out of the pay-to-enter zone and so likely to be only glimpsed from a moving car, is the most unusual sculpture here. Jenny Kendler describes herself as ‘an interdisciplinary artist, environmental activist, naturalist and wild forager who lives in Chicago and various forests’. Her Birds Watching, 2018-19 (top and below) is a chromatically-organised array of one hundred reflective eyes on aluminium, each representing a bird threatened by climate change. The flock is presented like a motorway barrier, making good sense of the admittedly inconvenient location at which we, as a bird watching species, become the accusatorily watched.

It would be eccentric to visit Eden if you were unmoved by nature, but given that kernel of impressive and site-resonant art, it wouldn’t be ridiculous.

Art writer and curator Paul Carey-Kent sees a lot of shows: we asked him to jot down whatever came into his head