The rainbow has become a ubiquitous symbol of support for health and care workers, but it has of course long been a staple means for artists to import upbeat colour – so much so that it doesn’t have to be curved or follow the strict colour content to pick up the vibe. Here are four rainbow-channelling works which I like: superficially similar concatenations of rectangular blocks which have many underlying differences.

Ellsworth Kelly’s Spectrum IV (2015) recalls the colour juxtapositions he developed in Paris during the 1950’s, including previous treatments of the rainbow theme, but this late work is a subtly muted conjunction of 12 thin rectangular panels. Kelly (1923-2015) was gay, and one thing which emerged in the gap between those rainbow engagements was the LBGT ‘rainbow flag’, adopted from 1978 onwards. I wonder if that was in his mind in returning to the theme…

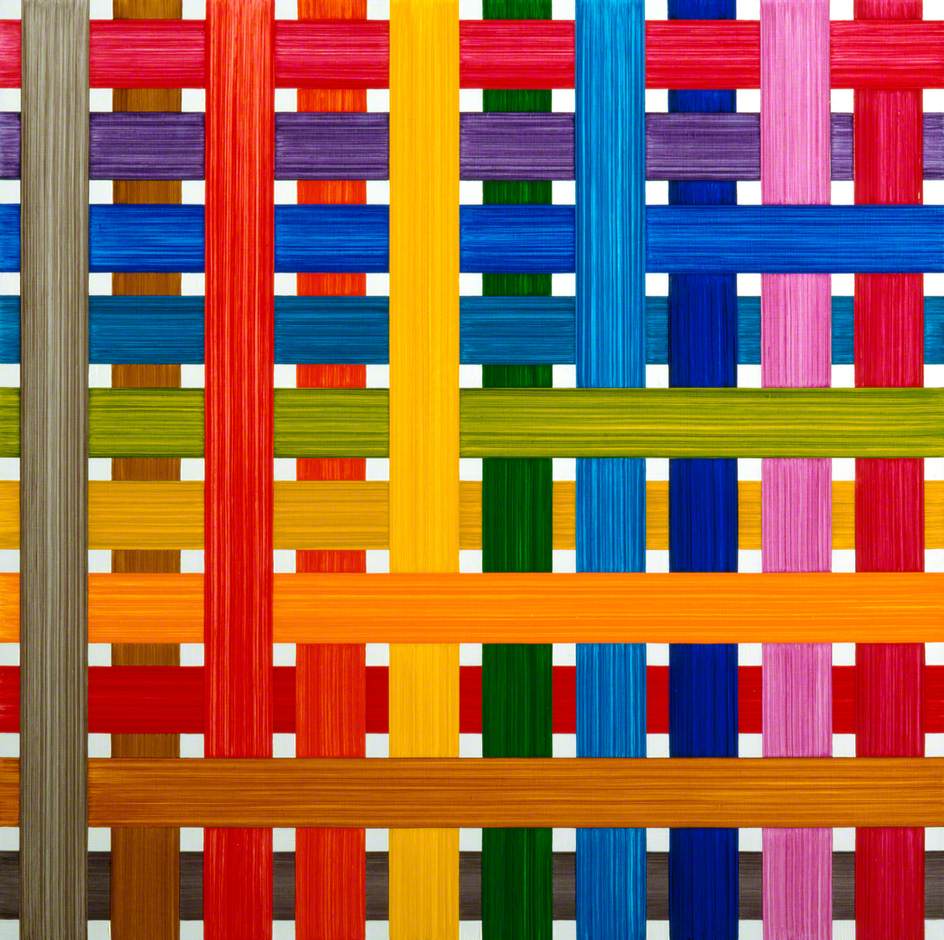

Kelly said he didn’t want to paint an overlap of colour, making it an illusion, so he used separate panels to produce real overlaps. In Jonathan Parsons’ I Love the World (Simple Cubic Array), 2000, the bands of colour appear to weave between one another, creating a sense of overlap and depth, but he’s actually with Kelly: the bands merely abut one another, existing side by side. The complete grey band, which looks as if it was painted last, was in fact the first to be laid down. Moreover, in this ingenious work, each hue occupies an equal surface area and, as paler and darker shades, is used twice.

A ‘dyade’ is an ensemble of two elements, and although Bernard Frize has said that his chooses titles to avoid any connection to the painting signified, this ‘vanishing point perspective painting’ (to adopt Terry R. Myers’ classication) Dyade, 2012, may be an exception. does combine not just oil and resin (as is usual in Frize’s work, explaining the characteristic look of colours not quite taking hold) but the frontal view with the illusion that we are not placed frontally after all. Is it, perhaps, anamorphic if approached from the side? Just one of the remarkable number of ways Frize has found over forty years to, in his words, ‘find ideas for which the paintings become the manifestation’.

Christina Niederberger‘s ‘Penelope’ 2020 is one of many works which take down ‘male masters’ of painting history through imaginative adaptations of their work rendered in such historically feminine forms as lacework, crochet or embroidery – this is a loose adaptation of Mondrian. She does this, though, in oil on canvas, so actually taking forward the medium critiqued. The detail of the brushstrokes here is such that, in her words, in another neat twist, ‘it almost mimics the weave of the canvas it is painted on’. Not surprisingly, Niederberger sometimes ‘felt like Penelope weaving/unweaving a shroud waiting for Odysseus’ return as the slow and repetitive process became a means to visualise the passing of time in isolation’.

Art writer and curator Paul Carey-Kent sees a lot of shows: we asked him to jot down whatever came into his head