Most people just stop making art after art school, because you have to work your arse off in London to just live here,” says artist and designer Graham Sayle, his soothing Liverpudlian tone peppered with concern. “Unless you live a completely illegal life – shoplifting all your food, living in a squat – how the f*** do you make art? Traveling across London costs enough. Having a studio and a flat – you’ve got to take home a lot of money to do that and if you’re taking home enough to do that then your job is pretty much your life. You’re f****d unless you’re rich really.”

This isn’t just conjecture. A study carried out by Luminate Prospects in 2018 showed that just over 20% of UK fine arts graduates actually go on to work as artists. Statistics like these reflect the challenges faced by artists like Sayle who are trying to balance a creative practice and survival in London – a city slowly suffocating its creatives.

I’m in Sayle’s workshop in Catford, South East London, surrounded by large pieces of beige and industrial green machinery, offcuts of wood, unfinished furniture parts, and a few students pottering around working on various projects.The workshop is big and impressive and probably expensive to maintain, something that would be out of reach if it wasn’t for the fact that it’s also part of the Catholic school where Sayle is a full-time Design and Technology teacher. “Having this space and working in a school – having the workshops, having the machines and being able to filter off certain materials from the school is invaluable,” he explains.

Sayle’s situation is not unique. London has become increasingly difficult for artists and creatives to survive in, let alone flourish. As the city gets more expensive and rents rise – they are set to increase by 15% in the next three years, according to property agent Saville – creatives are having to adapt. But history has shown that similar periods of hardship have also seen some of the most interesting movements in art, music and culture. The recession of the late ’80s and early ’90s was arguably a catalyst that sparked movements like rave, Brit-pop and the YBAs, for example, while post-war austerity of the 1950s coincided with the single most important cultural shift of the last two decades – postmodernism. The 2008 financial crash – and the subsequent fall-out, still being felt today – could be seen as a driving force behind much of the art coming out of London. The flip side of this, is a generation of artists being forced to compromise their practices, in innovative and creative ways.

As well as making art and working as a full time teacher, Sayle designs, makes and sells furniture. These pieces – made from smooth, poured concrete, wood and metal – are almost a byproduct of his art practice, but have become a means of subsidising it. “What I was originally making with concrete, that could be described as abstract art, can quite easily be monetised because it can develop into furniture,” he explains. “Stick some legs on it and people buy it, which I find hard because I feel like I’m compromising myself and it’s lazy. You can’t make the work that you want to make a lot of the time even without having grandiose ideas.

“I make furniture to make art and I work hard to make art, but I understand that art isn’t going to make me any money. I’m sure there is this amazing ‘sweet spot’ where people are making things that they’re super happy with that are commercially viable and they’re just living off art, but it seems increasingly difficult in London.”

Sayle began developing his practice in the early 2000s, in a London that seemed to have space in abundance. “I would break into old spaces and do shows in them and use them as a vehicle to show people the possibilities of these spaces having alternative uses,” he tells me. “I’ve always found it fascinating – going into places you’re not meant to go. I did a lot of stuff where I’d remove whole rooms and rebuild them in a pseudo Gregor Schneider kind of way.” Now in a city where property developers are waging war on public space and buying up every disused building they can get their hands on, opportunities to exhibit in an unconventional way are scarce. The Guardian was already reporting on this phenomenon by 2012, using the redevelopment at Kings Cross’ Granary Square as an example, highlighting the shift from private companies owning spaces like shopping malls to acquiring swathes of open space, once part of the public realm.

“Large parts of Britain’s cities have been redeveloped as privately-owned estates, extending corporate control over some of the country’s busiest squares and thoroughfares,” The Guardian wrote then. “The developments are no longer simply enclosed malls like Westfield in White City or business districts like Broadgate in the City of London – they are spaces open to the sky which appear to be entirely public to casual passers-by.” There is now corporate control over some of our busiest squares and thoroughfares; business is literally taking away our public space piece by piece, gradually and subtly.

Mike Ballard is a London-based artist that also explores the increasingly blurred lines between public and private space, ushered in by this relentless development. He uses the byproducts and detritus of a constantly mutating city to make monolithic, geometric sculptures constructed from the hoardings that surround London’s building sites. “The actual word ‘hoarding’ comes from when people had battlements, it was to do with fortification and ownership – it made me think about that and private and public space,” Ballard explains as we sit in his East London studio, under one of his latest constructions.

“It was only after using the material that I started thinking about all these other levels because initially I was drawn to it for the painterly qualities of graffiti removal and the weathering. Before I started taking the hoardings I was making paintings that looked like hoardings – of all the sort of layered paint and buff marks of the graffiti being removed and painted over and removed again. Where I was living at the time in Clapton there were these beautiful hoardings that had loads of paint on them and I thought, ‘Why not just take them?’. That idea sort of made the paintings redundant, because I was trying to replicate what was already there. If I take the whole actual thing it has the provenance that it’s real – that it’s done by an unpainterly hand.”

Although Ballard’s work explores issues like redevelopment, displacement and gentrification, he’s not making an explicit socio-political statement about them. He sets out to document or map the change, rather than to have an opinion on it, using parts of the city to develop a language that communicates that change, whether it is for better or worse.

“I started thinking about all the social connotations of it [his work with hoardings] – who owns the city? The amount of hoardings I was then aware of just made me realise the change in the city and how it’s being developed and what type of areas I’m going through to try and find the hoardings,” Ballard explains. “I’m not trying to have any view on that because it’s change, it’s progress and no matter what it’s gone on for centuries. People say ‘Oh that area isn’t like it used to be’, but no area is – everything changes. You can’t hang on how Homerton or Clapton used to be in ‘the good old days’ when everyone was shooting each other.

“I’m not trying to say anything political with it like, ‘I’m anti gentrification’ or ‘anti property developers’. I think there are negative and positive effects from both. You do see communities disappear especially with artists because artists have always lived in the shittier parts of town – they make it cool and then it gets developed and artists can’t afford to live there. It’s just this constant thing. It’s like what’s happening in Hackney Wick now of everything getting changed into these luxury flats that are sold to people in China who never actually live there.”

Although Ballard agrees that the city can stifle creativity, he also thinks it offers something that other places can’t. “People often say, ‘Why don’t you just move out of London?’ But something definitely holds me here and inspires me,” he explains. “I did a residency in Plymouth and needed hoardings for that, and there just wasn’t the same quantity of materials there – they didn’t have the same amount of marks and textures on the surface because there’s just not as many people interacting with them as there is in London.” There’s something about the structures of the city and the idea of who owns them – as well as who does not – that is compelling for many creatives, despite the implications for those trying to live and make art there.

“My main interest I guess is this idea of space rather than of buildings specifically,” London-based artist Lawrence Lek tells me on a call from his studio in Somerset House, where he is one of a cohort of artists to be offered studio space. “I always wanted to make a practice out of that somehow and what they don’t tell you at architecture school is that – in terms of the industry – it’s essentially property development.” While he’s lucky enough to have a studio right at the heart of London’s art establishment, Lek is still concerned with space and who does (or does not) have access to it.

Born in Frankfurt of Malaysian Chinese heritage, Lek studied and worked as an architect before fully establishing himself as a visual artist. He has firsthand experience of the challenges presented by an ever-expanding city, which also feeds into his work. “I was studying in times of New Labour and cultural capitalism and when I finished austerity was just beginning,” Lek remembers. “I was projecting forward – I didn’t really want to be designing boutique houses for the rich and famous. I was always interested in the philosophical side of architecture and also the historical, sociological aspect of it. More this idea of that architecture is a language that expresses society’s unconscious somehow, which gets channeled through industrial means, but then the idea that it reflects cultural aesthetics and also the currents of the economy and what structures society builds to house its collective institutions; whether that’s museums, town halls, social housing, public squares, urban planning and things like that.”

Lek is now represented by Sadie Coles – a prominent London gallery – shows his work internationally and has projects commissioned regularly by high profile clients, but has faced challenges that have shaped his career. “Barriers to entry start really f****ing young – institutionally it’s a huge problem,” Lek ardently explains. “One thing I have observed in British creative culture is that there is a huge paradigm of the ‘working class hero’ and it’s an extremely compelling narrative – the rags to riches, David Copperfield, Dickensian rise. As an immigrant I get that totally, but a big difference that I feel has quite destructive longterm effects is this widespread perception that there’s always an entry point no matter what your perceived barriers are – ‘If there’s a barrier just go round it. You don’t have a studio? Work at your desk. You don’t have a desk? Work in a cafe.’ I’m super aware of my own privileged point of view. I’m an immigrant and have educated parents – not just educated parents, but parents that valued education. There’s various stereotypes about South East Asian immigrants valuing education because that’s the meritocratic part of your lot in life.”

He makes what Lek calls “three dimensional collages of found objects and situations”. These site-specific virtual worlds use gaming software, 3D animation, installation and performance. By rendering real places within fictional scenarios, his digital environments reflect the impact of the virtual on our perception of reality. “Site specific sculptors like the ‘Land Artists’ like Robert Smithson were dealing with this idea of place as in this particular spot on the earth is super important,” Lek explains. “That was quite a compelling idea when it’s a climate of generic globalisation or the idea of digital production where everywhere can be the same. I then thought, ‘How is being site specific relevant in the virtual realm? How can you draw from contextual ideas – like in the case of Peckham in South London – while having this playful ironic vibe to it and also not just be a direct criticism of, let’s say, capitalism?’ It’s both an observation as well as something that could be taken very seriously.”

For the Dazed Emerging Artist Awards in 2015, Lek created a site-specific work about the Royal Academy. He built a fictional narrative around the idea of Chinese billionaires buying the former stately home turned public institution, and transforming it into a private mansion filled with ludicrously expensive art. It may seem fantastical but raises genuine concerns about the privatisation of cities like London. Like Ballard’s work it isn’t pointing fingers so much as offering analysis and possibilities, even if Lek’s tongue is firmly in his cheek.

His recent work at this year’s BoldTendencies, located at Frank’s Campari bar in Peckham, follows similar themes and addresses how we denote space in London. “In the White Building in Hackney Wick, where my studio was, the building was managed by Space but the ground floor was taken over by Crate Brewery.

“So similarly to how Bold Tendencies is actually known in the cultural imagination as Frank’s, and the White Building was known as Crate Brewery, which obviously pissed me off all the time,” Lek recalls with smidgen of disdain. “It’s the fact that most people just want to go out, so these places being a cultural destination is essentially fuelled by neoliberal down time where people go for drinks after work and I can’t really be completely against that without being an arsehole.

“I’m obviously complicit in the transformation of these places, but what I was trying to do with some of my work is in the future, looking back at it, it’ll act as an archive or portrait of a place in a specific point in time, so there’s those elements in it as well. I remember when Bold Tendencies started – I think this is maybe their 13th year – so in terms of a self-initiated project, the transition from ‘pop-up’ to a sustainable thing is an interesting trajectory.”

Lek’s academic background has given him a level of business acumen, something that most London creatives have had to develop to keep their heads above water, allowing him to make a living: “The way I consider my life is that I’m a contractor, but I’m a contractor in the sense that for content production. I basically get paid to do projects and if those projects get bought by collectors or institutions, which in some rare occasions they do, then that’s great if it doesn’t then whatever.”

Lek raises legitimate concerns about space that effect many creatives in London; even if he’s not one of them. While he is lucky enough to have a sizeable studio in one of London’s renowned art institutions, this is not the case for most emerging creatives.

“You have to try very hard to be an artist in London now, but I think interesting things can happen.”

DKUK is a gallery/hairdressers in Peckham, South London and is the brainchild of artist and hairdresser Daniel Kelly. He founded it in 2013 in response to the lack of affordable creative space, initially as a series of pop-up spaces around the capital.

“I started hairdressing when I was 17, because I didn’t have anything else to do. I’d failed my A-Levels and wanted a job where I didn’t get dirty,” Kelly tells me with an air of sarcasm, in the back room of his now permanent salon. The space is bright and busy and everyone seems young and fashionable, which is what one might expect, but where you would usually find mirrors and pictures of coiffed hair there is an exhibition by artist Sadé Mica. “It’s a completely different engagement with art,” Kelly explains. “We have a lot of regular clients who come every two or three months and they’re seeing a different show and spending an hour or so with that art work. It’s a very different way of looking. On average as you walk round a museum you look at a painting for nine seconds. It’s a bit like when you go to a private view – you might not be looking at the work the whole time, but you’re there and you’re hanging out with it and you’re perhaps thinking about it while you’re talking about something else. It’s a bit closer I think.”

His interest in showing art in an unconventional setting may stem from a somewhat unconventional path into art, but it’s an approach that is becoming more common in London as the number of affordable spaces dwindle. Galleries are having to be increasingly resourceful with how and where they show art, and many of them are adopting a nomadic approach with no permanent premises, or finding ways of subsidising what they do. For DKUK – as with Sayle and his furniture sales – the hairdressing element enables the gallery to exist. “If I talk to my brother, who is all maths and figures, I say ‘It’s half gallery and half hairdressers’, and he looks at the balance sheet and he’s like, ‘No it’s not. It’s 20% gallery and 80% hairdressers’,” Kelly chuckles. “They do support each other in other ways – why would people be coming to us if we didn’t have the art program? It depends which way you slice the cake I suppose.”

Kelly grew up in the North of England in a working class town. He trained at Toni & Guy for four years before he decided that the conventional salon environment was not a place where he wanted to develop his career. It was through an interest in fashion photography that Kelly decided he wanted to study art and moved to Peckham to study Painting at Camberwell College of Arts. He continued to cut hair one day week, but his life had taken a complete departure form his time at Toni & Guy. “Once I started studying art I really thought that I had found my place in the world – I felt much more comfortable and much more myself,” Kelly reminisces.

After graduating in 2007 Kelly worked as an artists’ assistant and made his own art. He was lucky enough to exhibit and sell work in renowned galleries like Matt’s Gallery and Saatchi, but found it difficult to exist as an artist after 2008’s economic crash. “I did seven or eight years and I was thinking, ‘How is the next seven or eight after that going to work?’” Kelly explains. “The climate had changed since I graduated. In 2007 it was very much still a possibility that you might sell your degree show and get gallery representation and make a career out of selling art, but in 2008 the holes started to appear.

“By 2013, which is when I first did the pop-up of DKUK, a lot more people were talking about having second or third jobs and how you could sustain a creative practice in London with it being so expensive. DKUK just came out of desperation really, and needing to find a job that was a bit more stable and thinking about income and art practice and how you balance those two things.”

Kelly had always had the idea of combining the skills he had developed – art and hairdressing – in the back of his mind, but hadn’t worked out a way to bring it to fruition. “When I started at Camberwell a teacher said to me, in regards to me leaving Toni & Guy to go to art school, ‘You’ve come a very strange route to get here and don’t forget how you came here’ and I was like, ‘Oh whatever. I don’t want to be a hairdresser I want to be an artists now’, but actually he was totally right,” Kelly explains.

He would give curators and gallerists haircuts in his art studio in the hope of having wider conversations about working on projects together, but these visits didn’t work out that way: his clients would talk about anything other than art: holidays, the weather, the usual salon chit-chat. It wasn’t until a friend gave him the keys to (the now defunct) Ancient and Modern gallery near Old Street that the idea of combining the two areas of his life was realised.

For the month of August 2013 Kelly turned the space into an installation inspired by his duel vocations, running daily events and creating a social hub focusing on the exchange of ideas. “Something about it being a hairdressers made it a bit more open,” Kelly remembers. “I did a different time-based artwork everyday and started with a few things on the wall, but added to it as we went along – like photos and ephemera from these performances. It was very much like an art installation where I was cutting people’s hair. There was something about having the hairdressing chair in there that made people come in – it became a really social place.

“I grew up in a working class town with not much access to art and I didn’t want my career in art to feel too dislocated from that. The hairdressers seemed to bring that together – people could come in and be in a comfortable environment where they could talk about art.”

After the exhibition’s success Kelly moved into a small unit in Holdron’s Arcade in Peckham and began developing an eclectic program of exhibitions to combine with his salon. “Because we are a hairdressing business we have a real freedom to the artists we can show,” Kelly explains. They have shown established artists like Richard Woods and Alan Kane, but also have an emphasis on the emerging: “Lots of places say they have a broad spectrum but I think we really mean it. We’ve got a lot of freedom with the program.”

Now up the road in the much bigger, permanent salon, DKUK has room to develop a wider exhibition program, but only because it is heavily subsidised by the hairdressing. In times when funding to the arts is tight and space is almost non-existent, creatives have to adapt, which isn’t always necessarily a negative thing. “When I was at uni there were a lot of artists making a lot of shit art – selling it – people would go mad for it buying all sorts of crap,” Kelly remarks, sniggeringly. “I remember in 2008 me and a friend said to each other maybe there’ll be a bit more good art made now. You have to try very hard to be an artist in London now, but I think interesting things can happen.

“This [DKUK] never would’ve happened if we were still in times where people were just buying stuff and not really thinking about it. I think my positive side would say it has forced interesting stuff to happen. I’m an optimist and I think we will always be here and make stuff, and maybe the interesting ideas find a way through the tougher times whereas if it was always easy going I don’t know if that would happen.”

Another unconventional space existing against the odds isThe Bower: a collaborative project between Louisa Bailey and Joyce Cronin, consisting of a gallery, publishers and cafe in Camberwell’s Brunswick Park. The gallery space and publishers are located in a disused public toilet while the cafe/bookshop is in the park’s old storage hut, down a winding path from the gallery, flanked by trees, tennis courts and a well-used children’s play area.

The Bower began its journey when Cronin invited Bailey to curate book selections for exhibitions she worked on at Central St Martins university. For three years they worked on shows together, before a colleague of Cronin’s offered them an old barber shop in which to hold a pop-up exhibition and bookshop. “Louisa set up her bookshop and we held events and performances. We also invited a project called Open Barbers to be in residence there. It was through doing that that we found this place [The Bower],” Cronin tells me.

Open Barbers gave them the idea of finding a council-owned building to make themselves a more permanent home. “We saw this little building on Southwark’s website and thought we’d have a look,” Cronin explains as we sit beneath exposed wooden beams in the neat, compact gallery space that’s hard to imagine being a toilet. “It was actually advertised as twice the size as the previous tenant had marked out some foundations. We turned up in the dead of winter – it was really bleak – and we arrived at this place that was half the size of what we were expecting and I think that put a lot of people off. They were like ‘what are you going to do with this?’ because it was completely derelict. We had a look around and there was a low ceiling and and no floor and grills over the doors and windows. No electricity or water – nothing.”

It was hard to imagine the dilapidated, old red brick toilet as a fully functioning gallery and publishers, and it had laid empty in the park for years. But the park’s proximity to major South London arts institutions and the dynamic art scene in Peckham made the location a geographical no-brainer. “Everyone went away – we had people advising us – a surveyor and family and stuff. They said, ‘You will never be able to do everything you want to do in there, it’s impossible. It’s just too small. Forget it’,” Cronin recalls. “We did look at other shops. We looked at spaces that would have been perhaps easier but we kept coming back here. We really loved the park and we really loved the weirdness of the building and the location – we loved being close to Peckham, close to South London Gallery, close to Camberwell College of Arts. We kept coming back and we would go away and imagine it bigger in our heads and come back and it would still be small.”

Eventually they decided to take the building and begin the long process of procuring it from the council. This meant months of bureaucracy and back-and-forth with Southwark, including working out how to pay the rent each month, a Change of Use application and obtaining planning permission for renovations because, as Cronin says, “it was still affectively a toilet”.

Although The Bower as an idea fitted in well to the landscape of the South London art scene, Cronin and Bailey were still unsure of how the local community would react to having a corner of their local park turned into a contemporary art hub. “We’re always very aware of being in the park and the sense of ownership people have over it as a public space, but we are still really committed to challenging contemporary artwork and believe that it is for everyone,” Cronin says with conviction. “I think this notion that contemporary or conceptual art isn’t for everyone isn’t true. I think people just need a way into it, and than anything that’s what we try to do – to give people a way in.”

They recently hosted a performance piece with artist Mary Hurrell, for example, titled Movement Study 6 (Maxxinna) – a “performative installation which attempts to create a 360 degree movement in sculpture” – which was possibly unlike anything the local residents had ever seen. Cronin says this had a real impact on the community: “It ran from midday on the first day for two hours and then two hours the next day, 2pm to 4pm, and so on until it ran up to midnight on the last night. People could view it from the window or come and stand in the performance space. For a lot of people in the park it was their first experience of live art and performance work. It was received really well.”

The Bower has earned the community’s appreciation, turning a disused, grubby, tumbledown hut into something that truly serves and engages local people. In a city haemorrhaging public space, places like Brunswick park are essential to the communities they serve. Adding something to that takes great care, thought and understanding. “The park feels like a little oasis – it’s quite an unusual space and we got that feeling straight away coming here even in winter and then it just got better and better,” Cronin tells me. “You get this sense of encounter that’s really important to the way that we work here. People stumble off the tennis courts, for example, and come in to find an exhibition by an artist that might not have come across before. They may never have been in a space like this and because of its location and its former use, it’s maybe less intimidating than going into traditional ‘white cube’ gallery spaces. With the cafe too you have different kinds of conversations in a social space like that than you would even in here [the Bower gallery] and definitely in other galleries. It creates this different way of people approaching and engaging with the work.”

The Bower grew out of a city where space is scarce and compromise is key, following official channels to obtain a tiny corner and turn it into to something enriching. To develop a creative practice in London now you must be prepared to operate in a certain way, but this wasn’t always the case. The city was once famed for – and proud of – its easily established, easily maintained creativity. Cronin and Bailey have definitely felt the impact of these restrictive changes: “The spirit of self-organising has always been crucial to artists and to making work and making publications. Spaces in squats and empty warehouses and all of those spaces are incredibly influential, but the available spaces in London are now gone.

“Where that used to be the way people operated, now those spaces have to operate in the pop-up. The temporary spaces before developers move in – it has to be much more of a strategic and known thing whereas before you could go into building not knowing what was going to happen. The cost of living was a lot less back then so you could also live in those buildings and run creative projects out of them.”

Furniture maker and artist Sayle is also acutely aware of the difficulty finding space, and has decided to reclaim small, disused parts of the city. Last year he turned London’s many antiquated phone boxes into mini temporary galleries for artists wanting to show their work in the capital. “I started noticing the abandoned phone boxes that are sort of non-spaces in London, because a company went bust and can’t afford to take them away and they f****ed themselves so they can’t sell them off,” Graham tells me with a defiant smile. “I thought for a while it would be nice to use those spaces because who’s going to stop you? So I cleaned some out, painted them white and began a little cycle of shows. The plan is to do a little art map and have a few artists showing in different phone boxes.”

As well as mapping the project, Sayle also likes the idea of audiences just happening upon the artwork and “being a bit baffled by it”. Sayle is adamant that DIY or stolen spaces are essential for less affluent creatives to survive here: “People shouldn’t have to be reliant on commercial galleries – being picked up by one or having a rich benefactor – which is what happens a lot of the time. You have to sell yourself. I personally think they’re [DIY art spaces] a lot more exciting – people doing art in the street or art out of context. I don’t necessarily think it needs to be in that world to be high art – there needs to be more balance.”

“Everybody I knew invented their own jobs…Basically you could sign on and you could get housing benefit and live on that.”

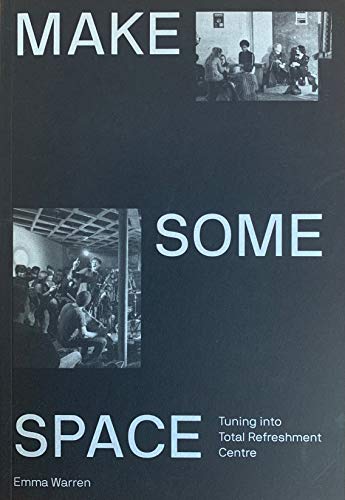

Journalist and author Emma Warren is someone who has extensively documented spacial changes in London, with her recent book Make Some Space. It is a comprehensive documentation of the Total Refreshment Centre (TRC) in East London, which morphed from a Caribbean social club in 2012 to a semi-legal music venue, art and music studios and rehearsal spaces. Its impromptu gigs and jams led to years of musical collaboration, and were vital in the development of today’s new UK jazz scene.

Warren describes herself as a documenter of culture and has been working as such for over 20 years. In the mid-’90s she co-founded Manchester-based seminal music and club culture magazine Jockey Slut and went on to write for publications like THE FACE, Dazed and The Guardian. She has a radio show on Worldwide FM, makes documentaries for radio, and spent six years as a mentor for the youth run, Brixton-based social project, Live Magazine. As someone whose career has been tied to DIY creative endeavours like Jockey Slut, Warren is a pioneer of London’s current DIY generation and regularly runs workshops for marginalised young people, introducing them to the creative industries. She sees parallels between now and when she first started out in the mid-‘90s.

“Economically in the North, it was kind of similar to now. I used to look at the Manchester Evening News, at this point in the ’90s, and there were no jobs ever advertised apart from working in a butchers for £80 a week,” Warren exclaims. “There weren’t any other jobs, so we literally had to invent our own and we did. Everybody I knew invented their own jobs. The difference was that you could get cheap housing and you could get Enterprise Allowance, which was like the dole. You could sign on and get housing benefit and live on that. We got the last year of it [Enterprise Allowance] – it was a Thatcherite thing. We squeezed in at the very, very last minute it was available.”

Although Manchester was, and still is, a much cheaper alternative to London (the cost of living is around 18% lower there), at the time of Jockey Slut’s conception, Warren explains that you could live on next to nothing – via side hustles and signing on the dole – and still produce creative projects. “We got 50 quid a week and we subsidised that with selling records at Vinyl Exchange. We’d get free promo records from record labels because we were journalists – everyone sent records. We would keep the ones we liked and sell the rest and that would pay my food bills or something.”

Warren got involved in TRC after visiting the venue for various music events, instantly seeing it as something akin to the semi-legal parties and venues that were common in London in the ‘90s and early ‘00s. “I accidentally found myself there, immediately recognised it as something interesting and then just went back as much as I could,” Warren tells me nostalgically. “I had no intention to document it or record it at all. All I wanted to do was enjoy it while it was there because it looked like it could easily not be there next week. I’d been going for a year or so and every time I went I just could not believe that it was still there or that it existed at all because it was so anomalous. It was anomalous in every way. It was anomalous in terms of location, it was anomalous in terms of vibe, It was anomalous structurally, personnel, what happened, how it happened – totally anomalous.”

During its short existence TRC became a hub for nurturing emerging and important music in the capital. Acts from the rising London jazz community, like Ezra Collective, Nubya Garcia and Sons of Kemet, all cut their teeth at the venue, which had an eclectic, inclusive and relaxed program. TRC attracted a diverse spectrum of musical acts and punters and became a safe space for those who needed it. “It had space, physical space – loads of it!” Warren exclaims. “There aren’t many places where you can go in and feel like you actually have room. The upstairs part where they were doing live music is just this big room, with a bar and a kitchen, so one: physical space. You could go in there and not feel hemmed in. Our houses are getting smaller – the streets are quite crowded – a lot of our public space has been removed form us and there aren’t many spaces where you can go and be like ‘Oh, there’s some room here!’. Two: I think the intention was clearly music first – it wasn’t about money – it wasn’t about anything apart from, ‘Oh that’s a cool tune – do you want to come and play?’ or ‘That’s cool – do you want to come and do a thing?’ It had less constraints than most places.”

TRC lacked the correct licensing for a venue of its kind and was one of the last of a dying, breed in London. Venues like that once flourished in the capital, their lack of correct authorisation and unorthodox approach a part of their charm and authenticity. “TRC had this unfinishedness. I’ve become quite interested in this as a concept in public space,” Warren tells me. “If I go into the Barbican I know that I can’t contribute because it’s finished, it’s complete, it’s beautiful, but it’s not inviting me to make my mark in any shape or form. It’s not inviting me to move a chair from A to B – if I do I’m probably going to be worried that a security guard will tell me off. In places with an unfinished quality I know that I can walk in and move all the tables to the wall, maybe put the chairs upside down if I want to, put some rugs out, build a little makeshift stage, put some things on the walls…I can adapt it for my needs. TRC absolutely had that unfinished quality.”

The idea to write the book came about after an encounter, in the slightly moody petrol station forecourt outside the venue, between Warren and TRC’s founder Alexis Blondin. “I said to the guy that runs it – who at his point I didn’t really know at all – ‘I just love this place. I come all the time because it’s so brilliant, I can’t believe it exists’, and he said, ‘Oh well it’s all over because the landlord has sold the building and it’s going to be closed down in a couple of months’,” Warren tells me. “I immediately sprang into action at that point because my immediate response was, ‘We need to document this while it is still here’. It was clear to me that it was going to be documented.”

This documenting is important because London, and in turn Londoners, is in real danger of losing important creative venues. Venues like this plant the seeds for important movements and moments in music and art, and then nurture them to fruition. Without this kind of cultural cultivation London risks losing the very thing that made it globally, creatively relevant, not to mention depriving young people of avenues through which to express themselves. “21% of UK nightclubs closed last year – 21%! I think that’s over 500 venues in one year, that’s a lot,” Warren says with frustration. “What you’re seeing there is a picture, and this is where it ties in with austerity, a pinching of resources from every single angle. Things that were previously plentiful – cheap spaces to go and do things – are almost nonexistent. The ones that do exist are harder to access, maybe more expensive, maybe more ‘proper’? There may be a slight layer of the formalisation or professionalisation or the health and ‘safetyisation’ of public spaces.

“We also previously had community centres or youth clubs where, as a young musician, you could go and find a space to do things, but the councils have sold over 12,000 public, community buildings since 2014 because they need to pay for austerity,” Warren continues. “They’re not even using the money to do things they are just paying for things like the redundancies that they’ve had to make for austerity. It’s selling the family silver for worst possible of reasons.”

Austerity and budget cuts have been a nationwide problem and have meant that people have had to adapt in all sorts of ways, but the cost of living in many other UK cities is cheaper, making a creative life in these places a much more viable option. What might be bad for London’s cultural landscape could be regenerative for cities in the rest of the country. “I think in some ways it’s about time, because it’s good for places like Liverpool and Bristol to keep brilliant people there, for Bournemouth or Middlesborough. If you have got someone who has got something it’s useful for your town or your city to benefit from that and for there not to be 100% brain drain, which I think happened for a long time,” Warren explains. “So I think London’s loss in that way is the gain of other cities. I do believe that it’s happening because people aren’t moving here in the first place. Some people who’ve moved here are leaving, they’re not staying for long, but there are also plenty of people that are staying in Liverpool, that are staying in Bournemouth and making stuff happen.”

Another important aspect of Warren’s book, mirroring TRC’s unconventional approach, is that it was completely DIY: published and released independently. Producing it in this way was important to Warren, but publishing of this kind is becoming necessity for a lot of Londoners without a platform to shout from. The project also had to be subsidised and supported by Warren’s day job, and completed in her spare time. It may sound like a daunting amount of work, but the luxury of being able to operate in this way and self-subsidise is one that a lot of creatives in London don’t have: their full-time jobs simply don’t allow the time or expense. “Total Refreshment Centre has this DIY aspect and then there’s my book, which is DIY published, which is a happy coincidence, but it’s not really coincidental,” Warren explains.

“The telling of the story needed to be like the thing [TRC] in order for it to be accurate. Even someone like me, who has quite a lot of advantages in the world – I’m a white woman of a certain age, which means I’m a homeowner. I’m also doing it in the gaps – I have to do these things around work – I couldn’t afford to do this full time. I have to have a job which pays for me to do things that subsidises this other stuff. Even though I’m operating under far fewer constraints than someone who’s say 25 or someone who is walking around in a higher melanin body, I’m also an example of where we are at the moment, which is a situation in which anything creative is having to be done in the gaps and despite the circumstances rather than because of the circumstances.”

When planning the book someone said to Warren: “TRC? I don’t think there’s a book in that”, but she was adamant there was. “If I had taken it to an agent or a publisher they would 100% have dissuaded me from doing it because they would’ve said, ‘It’s a bit weird – it’s a bit niche. A book about one music venue that hardly anyone’s heard of? I don’t think so’. If they had managed to get it then in the process of it they wouldn’t have let me unfold the story as I unfolded it,” Warren tells me in a very considered way. “I improvised the book into existence in the same way that TRC was improvised into existence. Also it was quite fun to do it that way. I had an idea in my head that I was like Wiley dropping white labels around record stores.”

“DIY” or “self-publishing” are terms loaded with connotations of illegitimacy and are often looked down upon by the publishing industry. Working in this way is something Warren is proud of, and as opportunities for publishing deals dwindle, for many in the capital DIY publishing may be the only viable option. As president of the Royal Literary Fund, novelist Tracy Chevalier has written: “Authors have seen their earnings chipped away at while publishers thrive. Most writers cobble together a living from several sources: teaching, journalism, and odd jobs. Writing is just one shrinking source of income. Shrink it enough and people will stop writing altogether. It literally won’t be worth it.”

Chevalier says the charity has noted an increase in applications for hardship grants from younger writers. This, she argues, reflects publishers’ hesitancy to take risks and support authors for more than one or two books at a time. This hesitancy means approaches like Warren’s are increasingly important. “’Self-publisher’ comes with a load of negative baggage, like I’m some crazy person that has written a thing that no one else is interested in,” Warren tells me. “It’s a bit shameful actually. If you say it to anyone in a bookshop they immediately recoil like, ‘Oh no we’ve got one of them in’. I’m quite proud of having set up an independent publishing house, which will have a life outside Make Some Space. There are already some books which I’ve commissioned and that are in process. Words matter and they bring with them a sense of what a thing is so I would say I’m an independent publisher – I DIY published it.”

“21% of UK nightclubs closed last year – 21%! I think that’s over 500 venues in one year – that’s a lot.”

Musician and artist Alexander Sebley is another of London’s DIY publishers, putting out his first book in 2013 – not because he couldn’t find a platform with which to express himself, but because he wanted to give voice to writers going unheard. “I wanted to work with people who wouldn’t normally have the opportunity to publish,” Sebley explains, tightly gripping his vape pen in a noisy coffee shop on Brixton Hill. “I like developing the person along with it. I wanted to help ‘outsider’ artists – the people who are on the edge. I think they do it because they have to. The thing about outsider artists in particular is most of them don’t have any money – it’s like the Bukowski poem: do it only because you’re compelled, you can’t do anything else. I like to find art within places you wouldn’t normally find it.”

His independent publishing house and record label 137 Albion Road has released two novels and an LP, largely financed by crowdfunding. They were intended to be non-profit, stemming from Sebley’s need to “just get something out in to the world” at quite a low point in his life, feeling stuck in a rut. He founded 137 Albion Road using a small-scale, manageable model: customers preorder books, which in turn pays for the production of more books. “It’s difficult because you are going out with your begging bowl – cap in hand,” Sebley explains. “It’s not perfect, but it definitely gives you an idea of the demand of something, which is good. It’s a lovely feeling knowing that actually people want to see you succeed.”

The first book released on 137AR – The Diary of a Cleaner – was written by a friend of Sebley’s that he grew up with in Portsmouth. Gareth Rees, who he warmly describes as “father number two”, was much older than Sebley – a bohemian, paternal figure in his relatively square and rough hometown. Alex and the local kids would regularly visit Rees’ dilapidated flat on the seafront to drink, smoke weed and listen to music. “Portsmouth is this very violent militaristic place,” Sebley explains. “There aren’t many weirdos, I suppose, and Gareth was definitely a weirdo. I was young and into music and I’d go up there where he’d be growing pot, and we’d play music and there would be lot of kids – it was kind of a squat. Gareth was like the ringleader almost – although he would hate that term.”

The Diary of a Cleaner was conceived from conversations the pair had had over the years and is made up of the many stories Rees told Sebley. The book also contains excerpts from chain letters sent between them and other friends discussing their collective existential crises. It was a turbulent labour of love and a difficult learning curve for Sebley in the process behind publishing, and one that Rees was never completely convinced about – unsure about whether he truly wanted to write a book. Despite this, the book was published, a fact made all the more poignant by Rees’ death last year from stomach cancer. “Gareth had an arresting power. He could’ve been a cult leader. When he spoke people listened and it wasn’t bullshit,” Sebley tells me looking visibly moved by talking about his old friend. “People can be very egotistical or buy into the hype of being someone that people listen to, but with Gareth it wasn’t like that. He was very humble simple guy.”

Sebley had relative success with this first book – it sold, something that’s never a given in the world of DIY publishing – and was able to release another in 2017, but he’s all too aware of the challenges producing work this way in London. “In the last 10 years it has become so difficult to live here. I’m seeing a lot of artists move away,” Sebley exclaims. “With closing the squats down it has changed things – it is not as easy to live here and have an ‘alternative’ existence, which I think is very damaging for a place that prides itself on its cultural relevance. It [London] is losing it massively and it’s at its peril. The arts are so important culturally – it’s one of the last things we actually produce in this country apart from technology, and we’re good at it. People forget how important it is and how much wealth the arts create. I feel like people think it’s not worth anything, but it is so valuable.”

The criminalisation of squatting in 2012 seems to have had a profound effect on London’s creative landscape.“Lots of artists, designers and musicians have all established their careers because they were able to squat. You couldn’t do that now. In a way it’s rebellious – it’s about not being beaten and believing in something other. By being here and kicking against the pricks, as it were, you are rebelling. Any alternative is rebellious. There are people coming up that are doing interesting things and people are finding ways to live here and create here.”

“Maybe it’s an old cliché, but I do think a little bit of hardship makes for better art,” Sebley continues, matter-of-factly. “Maybe under a Labour government we don’t have the best songs. Not to romanticise poverty – which I think goes on a lot, and I think it’s bullshit – but there’s definitely something in that. Anyone who pushes and keeps going with something – there’s merit in that. I respect anyone that does that because I know how hard it is.”

“One of the most rebellious things you could do in a time of austerity is to occupy actual space and time.”

Another creative thriving in the face of London’s many obstacles is André Anderson. A writer, DIY publisher of five books, headmaster of his own art college Freedom And Balance, mentor and brand strategist, he achieved all this before he was just 25. Unlike the other creatives I spoke to, the genesis of Anderson’s creative career was formed at the centre of the economic downturn in the UK, after 2008, so he has only ever known the need for adaptation and compromise when it comes to creativity. He is almost completely self taught and wrote his first book when he was just 18, which he wrote on his Blackberry Bold just so he could tell his friends he’d written a book.

Now 27, Anderson grew up on St Raphael’s (St Raph’s) Estate in North West London, where he still lives. The estate, like many others in London, has been made notorious by the press over the years, becoming synonymous with knife crime and gang activity. The estate saw a 107% rise in crime in 2018 despite attempts to regenerate the area. “Before I made something for myself no one said, ‘Hey we can help you’ because no one would know about you when you are from here. You really have to do it because you love it,” Anderson tells me, at Wembley Park tube station on a sunny afternoon in August.

“I personally never felt like I was seen. North West [London] doesn’t have any creative hubs – we’re not like East London. We don’t have cool, quirky, creative things to be part of. I work in Shoreditch now, where there is a lot of creativity, but coming from North West you have to work so hard to get there. I didn’t really think I was going to be seen by any publisher so I had to work out how to do it myself.”

As travellers exit the station and head down its steep staircase, they’re faced with a gleaming, new concrete and glass promenade, cutting its way up to Wembley Stadium. It’s dotted with branded coffee shops, a Getty Images museum and the unmistakable stamp of gentrification: a Box Park. The new development shows that plenty of money has been pumped into the area, but it seems cash like this is intended to attract outsiders looking for high-end apartments rather than to enrich the lives of those already living there.

Anderson is keen to show me a different side of where he grew up and gives me tour of St Raph’s, five minutes from the shiny new complex. His estate is like many others in London – uniform, beige low-rise flats with wooden cladding – and seems relatively serene on this summer afternoon. We walk past blocks named after scientists like Einstein and Darwin, and Anderson is obviously very proud to be from here despite the area’s issues.

Anderson tells me the reason he never got involved in crime on St Raph’s is because he didn’t play football on the estate, spending most of his time at home or at his grandma’s, reading and making comic books or lost in his imagination. He also attributes his positive direction to being exposed to MCing as a child, but also to growing up in the Pentecostal church. “In terms of areas like this rapping is one of the main forms of poetry and main forms of expression, even though after a while people do slip out of that and end up getting jobs and doing what they need to do in order to survive,” Anderson explains.

“Growing up you’d get judged on your wordplay and how you use words. That was reinforced with me because I grew in a Pentecostal church. The idea of it is that I grew around people that weren’t speaking to impress anybody they were speaking in order to reach God so there is a different level of intensity. Being brought up in that environment where every single week you were expected to read text and be able to say how it’s relevant to the present day gives you a level of purpose behind your words. And it gives you a purpose in terms of life in general.”

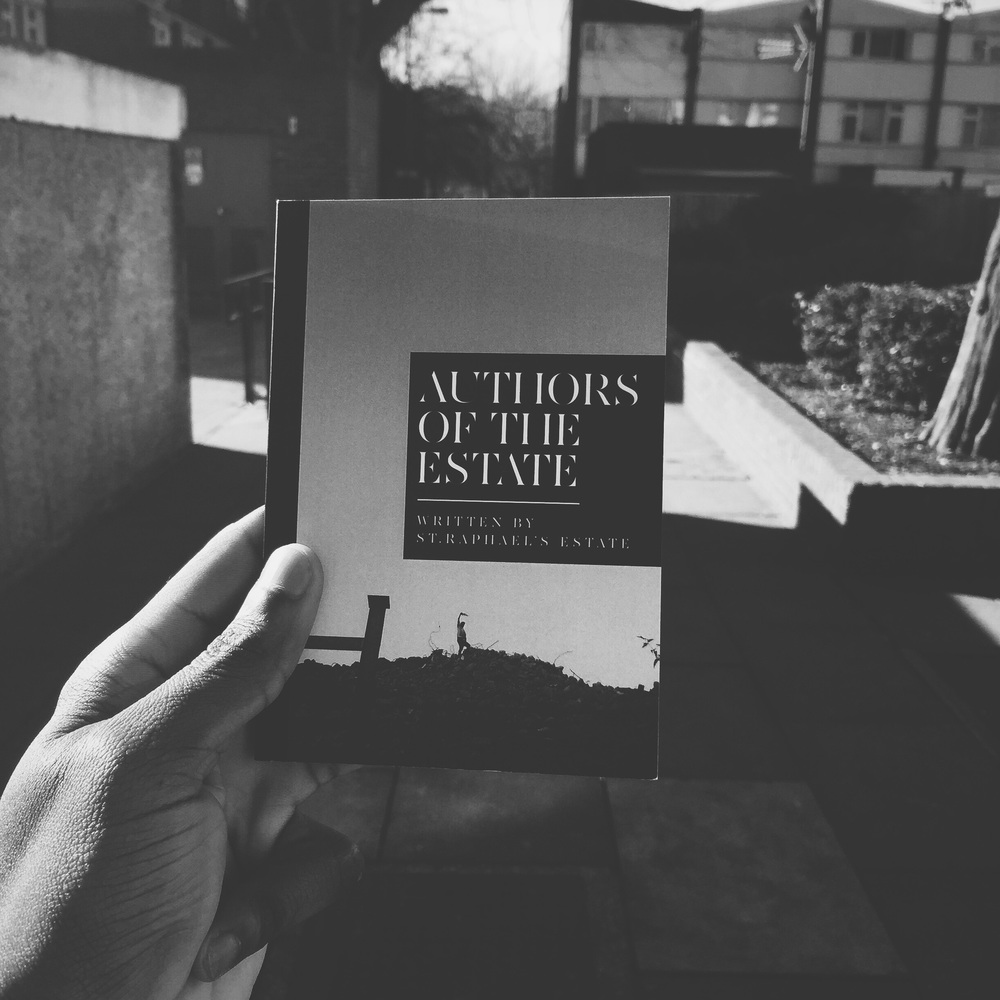

Anderson has just released the second instalment of his Authors of the Estate [AOTE] series. The books, compiled of stories of local residents, are designed to give a voice to those who wouldn’t usually have the opportunity to write down their experiences, let alone have them published. The first was released in 2015 and was posted through the letterbox of all 1,000 St Raph’s residents. “I thought, ‘What would happen if we were to make a book and give to everyone in St Raphael’s Estate? So we did that,” Anderson explains. “It was me and five other authors from St Raph’s and we wrote down our experiences – it didn’t have to be pretty it just had to be honest. We were going to tell our story and not rely on someone else to tell our stories. We did it for proof – to say we exist. We were saying ‘I know we perceive ourselves in certain way, but here is another way to perceive ourselves – this is what we can do!’”

Anderson’s aim has always been to enrich the lives of those on the estate by broadening their horizons and showing people first-hand that there are ways to express their feelings and experiences. He understands that as opportunities become more and more scarce, individuals and communities are responsible for making their own opportunities – for themselves and for one another. “We were trying to achieve a new form of oral tradition. We wanted to get to a point where guys on the street were speaking about the new book that they’re writing and not just the new mixtape – even though mixtapes are important,” Anderson explains with an admirable level of conviction for someone of his age. “If I go to to Jamaica a lot of my family don’t read and some of them can’t read, but they get a lot of their journalism from music. It’s an important art form, but my question is how do we expand what we can do without textbooks – what can we do naturally? We’ve been able to get music and rhythm and spirituality down, but how do we inject things like literature and get design involved and things like that. We’re trying to implement new habits.”

The second AOTE book Chalkhill Edition is compiled of stories from the residents of the neighbouring Chalkhill estate. The stories were gathered through storytelling workshops held in the local area facilitated by Anderson and the book has been 100% DIY published by his team.

Freedom And Balance is also the unconventional art college Anderson has set up to focus on building local and sustainable creative communities. Its curriculum is delivered online, through newsletters and with workshops, intended to give creative opportunities to people who would not necessarily be exposed to such avenues. “When you see people like Gal-Dem Magazine [an online and print magazine, by women of colour and non binary people of colour] and Amaliah, which is a Muslim magazine based near here, and Freedom and Balance – this is a response to not feeling invited to the party. For a lot of us we are first generation creatives – we’re the first generation of our families to make money from creative thought,” Anderson tells me.

“The problem is you’re always seen as the little man, as a novelty. ‘It’s nice to have you around but we don’t want you in the board meeting and we don’t want you to be making actual decisions – you’re there to tick a box’. Also there is acknowledgement that there is obvious spice and sauce to what you are doing – it’s obviously working, but there’s also the feeling that it’s not enough for me to introduce you to my business pals. That’s felt – that’s felt in a real strong way. To anyone who is in the creative industries that’s from a family that’s not from England, basically, it’s deeply felt. The response to that is both building your own infrastructures so my children won’t ever have to have this long conversation, ‘Oh we’re not invited to the party’ and the second thing is to make sure that view point is challenged because even though it is a very quiet one it is very there.”

Unlike Emma Warren, Anderson never thought of self-publishing as having negative connotations. He’s part of a generation that is self-publishing everyday, via their mobile phones. “It’s getting less prestigious to get published. I think publishing companies are realising their prestige isn’t as high as it used to be because everyone is a publisher – people publish all the time,” Anderson explains, as we sit in the sun outside a Starbucks near the tube station, that feels a million miles away from his estate. “There’s a 14-year-old right now talking about their day and how amazing it is – when you’re on Instagram or Snapchat you’re publishing something. Whether or not we call it publishing, we are putting something out into the world and seeing how people respond to it. Publishing has become a daily habit, telling stories is a daily habit. I don’t think there is as much excitement around publishing as there was before we had access to a means of self-publishing content. Publishing has changed for better or for worse. For better because everybody gets the opportunity, and for worse because everybody gets the opportunity.”

Although Anderson’s practice has a footing in the fast-paced, ephemeral online world, he is very aware of the importance of also existing in the physical realm, of occupying physical space in a city where it is increasingly precious. “One of the most rebellious things you could do in a time of austerity is to occupy actual space and time,” Anderson vehemently explains. “The internet is not a real space or important space and it doesn’t really have time – there are no seasons on the internet – there’s no Autumn or Winter: it just is. Whatever is in front of you is in front of you and no one will remember it two weeks from now. Things that happen here [he gestures to the space around us] you can’t forget – it’s rooted in time. The people who actually take up spaces, the people who create print that takes up physical space, the people who create moments in time and not just moments on the internet, are the people who are important for this era. A time where space is increasingly restricted and it is harder to find space to develop yourself.”

Like Daniel Kelly and Alexander Sebley, Anderson is aware that adversity isn’t always a negative influence, in terms of creativity, and can be a catalyst that is very much needed to cut the wheat from the chaff and give focus to those trying to create. “Some of the most creative people I know are hella broke and they have to be creative because they’ve got boundaries. It could be that some of the most creative ideas that we have are going to be during the times of austerity. These could be the moments where actually the newness that we are looking for may come about because we have so much restriction. A lot of the fat that we have will have to be cut off and I wonder what will happen when we have more lean creative solutions rather than seeing creativity as this super, overflowing thing.

“Options are narrowing creatively, but is that a bad thing? I don’t know. For the most part we live inside a box. We normally say that we need to think outside the box and usually when we say that creatives go so far outside the box that what they create has no relation to the box that they are in. So it’s cool and we reward and give them a hand clap but it actually has nothing to do with what they’re making. There is power in thinking within the box – everything that is within my surroundings how do I reorganise it to make something new? But also you need to understand that there is no box.”