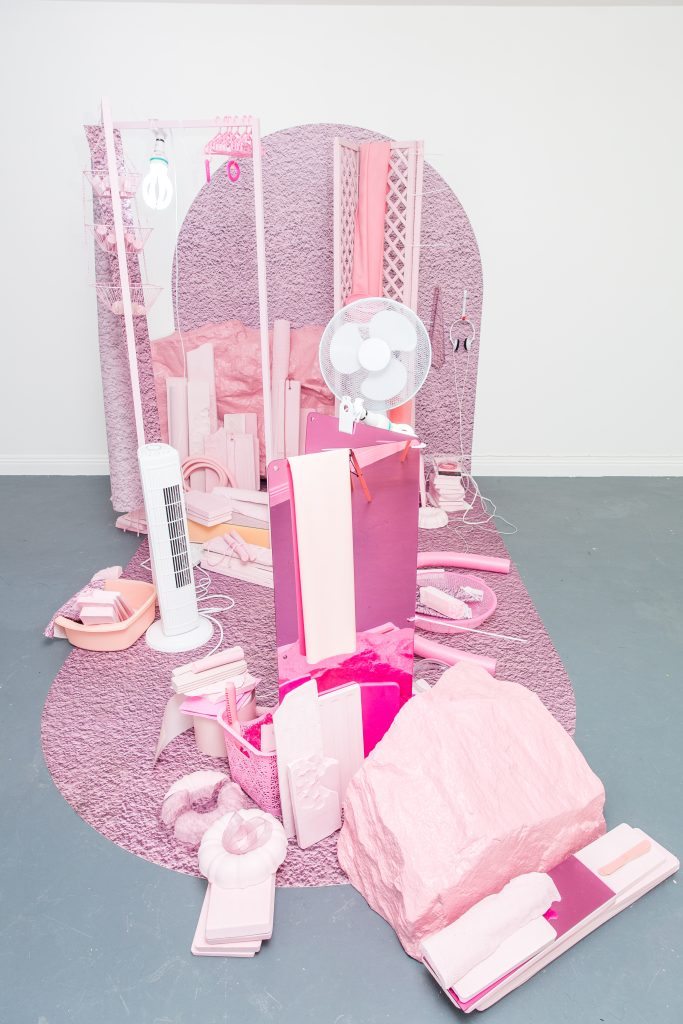

For her first solo show, Welsh artist Sarah Roberts travels to the Costa del Sol, creating an all-enveloping five-dimensional monochromatic installation at BLOCK 336 in London entitled Torremolinos-Tableaux-Tongue-Twister (After Sun) (on until 6th May 2017). This site-specific immersive exhibition is the second act to a 2016 day-time version of the beach in Torremolinos that was exhibited at HaHa Gallery in Southampton. As day moves into night, colours change. The pink flesh of bodies on the beach mutates into red – suggesting sun-burnt skin, red neon outside a nightclub or a spectacular sunset. In this exhibition, the viewers’ senses are completely overwhelmed with dozens of different surface textures they want to touch, atomisers spewing out the scent of sun cream, a sound piece of waves crashing on the beach and the ruddy pigmentation of the entire space. Red LED lights from above illuminate hundreds of objects that are either laying on the floor, leaning up against the wall or reclining on plinths, all of which are scarlet-tinged (including two tons of rubescent gravel poured onto the floor in the shape of a tongue). The objects include hand-cast plaster pieces, found objects, hand-printed textile pieces, glass, rubber and glitter. Living between London and Wales, Roberts writes poetry as well as makes sculptural installations that are obsessed with their surfaces and how they mirror the everyday world, recalling architecture, landscape and body in form and colour.

Congrats on your first solo show at BLOCK 336 in Brixton! As a viewer, it was a mesmerising experience for me, playfully engaging all of my senses. Instead of looking at each of the individual objects, the monochromatic aspect of the show forces you to dwell on the entirety of the installation. As the artist, how do you intend the viewer to interact with this all-consuming installation? Do you attempt to curate the viewer’s experience through the employment of excess?

Thank you! This has been my first opportunity to create something on this scale, and something that is in turn a fully encapsulated immersive experience so its nice to hear that your senses were aware of being catered for in the journey through it.

In terms of leading the viewer – I’d like to think I’m not directing their journey through the installation beyond the physical pathways that are created; maybe I’m more researcher and set designer. I want to lead the viewer to a space that’s akin to a [very present] stage set of the everyday made anew, somewhat credible and entirely real, part unfinished and very much made for a viewer to discover themselves, and in that act of discovery, to activate it.

When I’m researching for new palettes, I seek out places that show me their edges, their constructedness, facades, or ideas of underneaths. I don’t see these faces as veneers or fakes but as very real material surfaces, the actuality of things. The plastic paradise of a truly blue hotel spa, furred up purple carpet tiles, pinks plastered on walls as dripping renders, wet sand furrowed and grained, pressed into with bony fleshed out toes – all up for grabs. I’ve loved Vegas casinos, desert landscapes, Welsh hinterlands, and now here – the sun-down-lit strip of the Costa del Sol that is Torremolinos.

And about the excess, well yes, maybe if left alone with less, the viewer may have time to start making sense of things, to covet the object, to attribute the value of artwork to things; whereas here in the conversant and non-hierarchical material repeats, I hope viewers will focus on looking at the materiality of things or at best wanting to touch.

Personally, I was very drawn toward the hand-crafted objects in the installation – the screen-printed textiles and wall vinyls and the cast plaster pieces. Do you see these as able to exist on their own as individual artworks outside of the installation context? Or does your practice only allow for an installation type of presentation?

No, not at the moment. I actually find words or collage easier ways of representing ideas in smaller utterances. I use collage a lot in the preparation for a piece; it’s key in my research process.

Once I start making, the connectivity between the excess seems essential. It’s like the pieces all form an alphabet, and trying to exist alone, they are just the beginning or end of some sentence, never the core of it – they really are surfaces. Maybe this can change as my vocabulary strengthens, but for now, once things become 3D matter, it gets trickier; things gain this unwarranted value, trying to make sense and coming back senseless.

My practice as a maker has a focus on labour and production. I produce multiple repeats in a day, all different takes on a sensation, all chatting, and all growing into some overall sense of a new place. I am my own factory, and I access others who operate out there in the ‘real world’ of manufacturing to create things as well, and these are of equal stature, getting something absurd made to spec – where you can hardly notice it’s bespoke without closer inspection – is something I adopt a lot.

I have a special and fleeting relationship with each piece I make, and then each piece slips a little into the next and into the whole. I want that thing I have hand-cast to sit, with a sense of purposeful slippery belonging, alongside found plastic objects or those bespoke manufactured absurdities – all equals, all matter. I think this is what throws us into an experience of looking – me out there on the promenade in Torremolinos, and the viewer here in its Tongue-Twister counterpart at Block 336.

For this show, you wrote a free verse poem that was included in the press release. When planning an exhibition, what comes first for you – the poetry or the visual components of the show?

I use words at all stages of the process – to record places and their sensations. I write emails to myself, like material memoirs, hashtag haikus. Much like the materials of the installation, they get sculpted, become a collection of collisions, and seek to perform a function but slide into phonic performance kept together by proximity of placement and somehow making sense even at points of disjuncture. I began writing this poem in a café in Torremolinos and finished it on the tube after a site visit to Block 336.

In this poem, the opening line is “Her tongue twisted around names and melting ice pops as the dark closed in on the pinks and the sky clouded into sticky reds”. It is an incredible introduction to the show, giving the reader many clues to what they are about to encounter visually as well as aurally and olfactorily. Is it essential for the viewer to engage with your writing before or after viewing your work?

The poems are gobbets, non-narrative descriptions of the material encounters rather than a map of this new space. So no, they are not essential; they are not a precursor nor an afterthought. They are simply another thing.

In the past, your artworks had a strong tie to your own Welsh heritage, possessing titles in both Welsh and English and exploring the chroma of the Mid Wales countryside. How important is your own autobiography to your practice?

I believe Welshness runs through me and my practice like a granite seam. The older I get, the more I experience a sense of hiraeth [which translates as homesickness but more as a sense of longing for the land] when I spend too long away from Wales. The landscape back home is as tactile as it is visual. I grew up in a small town, a strip village nestled between rock and sea right in the middle, right on the coast. In the face of epic variegated terrain, tiny terraced dwellings become impotent teeth in crumbling pinks and blue hues against a backdrop of grey and green. We didn’t have iPhones in the early nineties, just skinny legs, mountain bikes and a sense of owning the rock from our bunk-beds whilst waiting for the summer season.

I now live and work between Wales and London. It’s perfect. Each place is as intense and revelatory as the other, and they keep each other blindingly visible. I think this has an undeniable effect on my practice. I will never get bored of working with Wales.

Given that words are part of your artistic metier, is the Welsh language something you wish to preserve in this world of disappearing languages?

Welsh was my first language; as a child, I barely spoke English, and now I lose words daily. My accent is unrecognisable. It’s an upsetting sensation of loss, both of belonging and of the fragility of our ability to communicate. It’s also fascinating; my words have become more material than ever as they trip and tumble from my mouth. I’m obsessed with the awkwardness of Google Translate and its limitations. I think being bilingual as a kid helped me to articulate. I chose words for their meaning, but also their phonics, their performativity. I circumnavigated them from the other tongue like one might a sculpture. I do this when I write, often using translations in texts or titles. In fact, I seem to love the imagery of tongues too!

I’m definitely interested in preserving language, and not for nostalgic reasons. I genuinely believe that multiple languages can add to our ability to perform proper attempts at articulation. I’m relearning my mother tongue to an adult grade now. It’s like my vocabulary was fixed when I left Wales at 18.

For your installations included in The London Open at the Whitechapel Gallery in 2015 and Saatchi Art New Sensations in 2014, a single colour was not the focal point; instead, a panoply of surfaces, faux and real, barraged the viewer. From a white plastic electrical fan to a scattering of hand-cast plaster bowls in a rainbow of colours and from a roll of LED strip lights to wallpaper and swatches of silk printed with a photographic image of polystyrene, texture seems like a key driver in your practice. Do you agree? Could you talk further on this point?

‘Barraged’ is a nice way to put it. That’s how I feel when I find these places in the first place. Buffered by winds, accosted by colour. Dribbling internally at the sheer deliciousness of the surface textures.

My practice centres around this collection of the actuality of the surfaces of the world; when researching, I collect images of walls, floors, sand – all texture, colour or form. The distilling of these textures starts here. I don’t see it as a reduction to colour, texture and form – its more like a making visible of it. The images are repeated into forms, poured into plasters, smoothed into ceramics and printed on various substrates with sliding scales, sound, scents and more. For each place, the representation I create is led by the overall sensation of that place as I record it – sometimes places seep into a hue, other times their apparent colour blocks stick out shouting, and sometimes the air smells like sun cream.

AMPERSANDS (Fairbourne a& Margate a&) (2015), shown at Whitechapel, is a piece centered around excess, additions and the power of visually driven connections. This piece collides two palettes through a forced additive connection and is slightly more frenetic and unnerving as a result. It’s full of of peeled-off textures of Margate’s visible arcadia and a bleak palette from a Welsh strip village that is slowly returning to the sea. This insinuated theme park of edges and collisions of made matter, in multicolour hues with washed out rocky accents, hopefully makes us consider these created visual contexts.

ETO O Borth – Again from Borth (2014), shown at New Sensations, is from a hinterland in Mid Wales, a more direct presentation of one palette, a strip of terraced houses exposed to the land and the sea. Its flimsy curtained ‘walls’ pull at the edges, suggesting Borth’s precarious positioning on the coastline and observing our belief in those tiny multi-coloured terraced invaders of the landscape.

Here in the reds at Block 336, this heavy lidded half light is an integral part of the encasing shell of the work. I’m fascinated with the idea of our experience of colour being waves reflected off the surfaces. That we are making it red, SEEING RED. I’ve included light in many previous works as a material, a light, a bulb, a colour. This is the first time I have really considered its impact on our ways of seeing colour, its ability to shift the palette of a place depending on the time of day.

I tried to fix that moment of light into an experience of colour, and I love how its unfixable and slips away from your eyes. I’m fascinated by this idea that the objects in a place can be different visible versions of themselves at different points in the day. The red is all-encompassing when you first encounter it and then fades as your retinas adjust to the light into salmon and oranges. The lights were the first things I installed so I could get a real sense of this new space – I had to keep going back out to the white light so I could see the reds again. You are very aware of your place within it and your experience of the colours changing whilst you are in it – this apparent colour cover-up that is in fact a revelation of textures.

LINKS

BLOCK 336, London: http://block336.com

Artist’s website: http://www.sarahrobertsfa.com

About the Artist

Sarah Roberts is a Welsh artist currently living and working in London and Wales. She studied Sociology at the University of Leeds (BA 2001) before finishing a second BA in Fine Art at Chelsea College of Art and Design, London in 2014. Recent group exhibitions include SellYourSelf, East Street Arts, Leeds (2017); I’M Feeling So Virtual I’m Violent, HaHa Gallery, Southampton (2016); P A N D I C U L A T E : The Joy of Stretching, The Koppel Project, London (2016); The London Open 2015, Whitechapel Gallery, London (2015) and Saatchi Art New Sensations, Victoria House, Londn (2014). Roberts was selected for the Into The Wild Residency Programme, Chisenhale, London (2015-16) and the ACAVA/ArtQuest Lifeboat Residency (2014-15), and was awarded the Parasol Unit Exposure Award in 2014.