Jeff Koons, ‘Gazing Ball (Manet Luncheon on the Grass’), 2015

The philosopher Stanley Cavell once remarked that modern art is characterised by the fact that you never know whether it is sincere. He was thinking about art in terms of language, whether the artist really means what they appear to be saying. Nowhere does this apply more vividly than in the work of Jeff Koons, for whom kitsch and fine art are interchangeable, always wavering between banality and acuity. In his latest exhibition, Gazing Ball Paintings, at Gagosian New York, Koons oversteps the mark of decency and demonstrates that the most horrifying thing about his art is its sincerity.

The gazing ball was popularised by King Ludwig II of Bavaria who set the trend for its use as an attractive garden ornament, but Koons has used them to adorn classical sculptures. These works are cleaner, more understated than practically anything Koons has done; they resonate with quiet reflection while their delicate curves and restricted pallet feel demure. They are the best looking, most mature thing Koons has done since the hoovers and the basket balls, but they are also, like everything Koons does, seductive, slick and postmodern, as if he has finally hit on the essence of his practice without the garishness and twee.

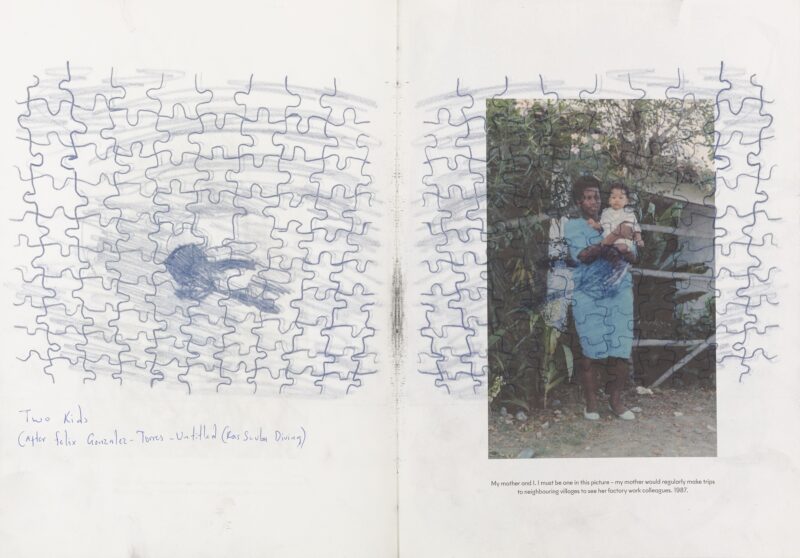

The latest outing for the gazing balls is somewhat more eccentric, and therefore more in line with our expectations of Koons. This time he has placed them on an aluminium shelf on the front of paintings, except that the garishness is back with a vengeance: the paintings are copies of the great works of art history, such as Leonardo’s Mona Lisa and Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass. The gazing ball, the same royal blue he always uses, seems to hover just in front of the canvas, always in central position. The effect is one of monumental incongruence – jarring, awkward, destabilising, just like the Koons we know and love. It is a brutal assault on the senses, not to mention a callous riff on art history. It is indecent in at least the sense that it often fails to work either aesthetically or conceptually, but it is always irresistible, beguiling in a way that you cannot quite articulate. Standard Koons, then.

Some of them work better than others, such as Gazing Ball (Turner Ancient Rome), where the contrast between the fiery, autumnal hues of the painting and the blue of the ball complement one another. It also works formally because the ball appears to be floating on the surface of the water, gliding downstream towards the bridge. Whereas the Mona Lisa’s gazing ball looks like a carbuncle growing out the girl’s side, with no apparent purpose or context in the picture. There is something unsettling about the physics of it all, of which Koons is very proud, saying ‘I engineered this and I feel really good about it, because all these things are somewhat an engineering feat’. The ball, which is attached to its shelf by a rod, seems too implausibly heavy compared to painting, adding a weight, or a burden, to the seeming effortlessness of what appears to be a masterful painting.

The paintings are fairly convincing copies, although Koons has taken liberties with the scale by making them, notably the Mona Lisa, much larger than life. There are 35 in all, with Rembrandt, Titian, El Greco, Courbet and Rubens all getting the Koons treatment. One assumes that without the gazing balls they would appear to be inflated, clumsy copies that look too new and too shimmering to be convincing. But with the gazing balls they are enchanting and completely earnest, for Koons seems to be presenting them without a hint of irony. He really thinks he is rethinking the canon of art history, following in the footsteps of Duchamp’s LHOOQ, but also adding something – an idea, an aesthetic, an expanded field of experience – to the canon. He says they ‘are all handmade paintings…These are as exact replicas visually as the originals, they’re different in size, they’re flat…because they’re just the idea of the painting. This is just the idea of the Mona Lisa’. It seems as if he intends them to be both faithful copies and conceptual gestures within the context of his practice.

The point of the gazing ball paintings, Koons explains with yet more irresistible soundbites, is not about copies but about the participation of the viewer: ‘This experience is about you…your desires, your interests, your participation, your relationship with this image’. One of the interesting things about Koons is that although his work looks overblown and self-indulgent, he has an uncannily convincing way of bringing it back to the viewer’s experience. The kitsch, after all, is about stirring our nostalgia for a non-existent past that we can never inhabit. It is as if Koons is that rarity in contemporary art – an artist who makes art for the audience, with the audience’s feelings and tastes in mind, which he goes to great personal trouble to explain and exemplify at every stage. Anyone who has ever heard Koons speak will recognise his tone which falls somewhere halfway between a sage in an impassioned trance and an enigmatic life coach. It’s almost as if he wants us to understand his art because he is expressing himself for our own benefit.

The sincerity of Koons is painful because there is no irony, no self-consciousness and no sense that there might be something wrong. He is like a naïve child, utterly unaware of how the world works and how it sees him, presenting the gazing ball paintings as both a serious engagement with history and an attempt to relate to the audience. It makes one weep to think about how soulless, disingenuous and utterly devoid of humanity blue-chip art is, but it also makes one weep tears of exasperation and sorrow to see Koons dreaming of a utopia where a Gagosian show is a window on to the human soul.

The problem with Jeff Koons is not the money, or the garishness, or the obscenity of his self-importance, but the fact that he really believes in what he doing, he really means what he is saying and he really, really wants to convene with us. This horrifying sincerity and lack of irony makes Koons one of the most brilliant, if unsettling, artists alive, for which he scarcely receives due credit. The trouble is that nobody, despite Nietzsche’s best advice, wants to gaze long into the abyss, for when the abyss of contemporary art gazes back, you see only yourself reflected in the surface of a blue glass ball.

Words: Daniel Barnes