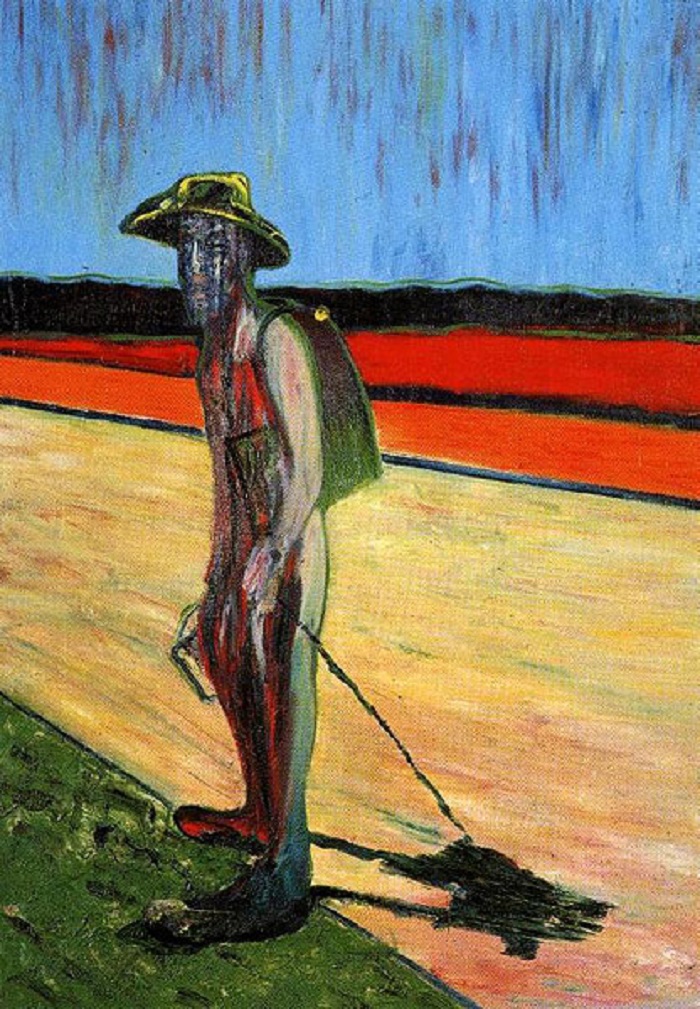

One of Bacon’s van Goghs

On the 24th anniversary of Francis Bacon’s death, 28th April 2016, the artist’s first definitive catalogue raisonne will be published, including over 100 previously unseen works and missing 4 that remain untraceable. Bacon’s reputation is built on a few greatest hits and auction favourites, but the catalogue promises to broaden the general view, offering a deeper insight into a complex artist whose work is seen in surprisingly shallow terms.

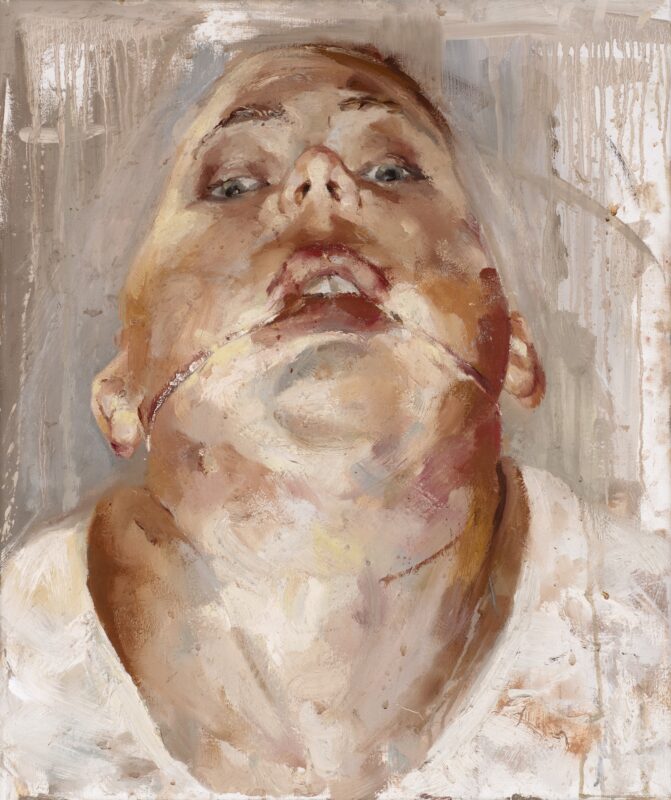

Francis Bacon is a great artist. One of the very best of Britain, of painting, of the 20th Century. Probably, without hyperbole, one of the best artists to have ever lived. But he is grossly misrepresented by the art market, which is saturated with popes and portraits – every contemporary art sale at Christie’s or Sotheby’s boasts a study for a pope or a portrait of someone doing something. It begins to look like Bacon never did anything else, which of course he did, but these works are the ones that are held in private collections and the greater portion of his output. Indeed, the popes and the portraits are the numerous, much-loved tracks on Bacon’s Thriller or Nevermind.

It is, then, a mystery why – if these are the most highly coveted works in the Bacon cannon – collectors are always so eager to offload them at auction time. One can only assume they have hefty gambling debts, draining crack habits or stupendously acrimonious divorces to fund. The preponderance of these works in the public eye have cemented Bacon’s reputation, and nobody doubts that Portrait of George Dyer Talking, for example, is one of the masterpieces of the 20th Century. But there is still an open question concerning whether these famous works are the best or the most representative – probably they are both, but the catalogue raisonne will finally answer that nagging doubt and reveal to us exactly what else Bacon did.

The other striking thing is how few paintings this reputation is built upon. It is well known that Bacon gleefully destroyed his works, going so far as to buy one of his own paintings for £55,000 from a Mayfair gallery and immediately stamping it to smithereens on the pavement outside. He would also leave rejected canvases in the cupboards of the house he rented in Tangier, going back year after year to destroy them. However, the seemingly endless flurry of Bacons on the market suggests they are abundant, but in fact our collective knowledge of Bacon is based on 180 paintings. That is a fairly small portion of the total 584 works collected in the catalogue raisonne, so one begins to wonder about the remaining 404 paintings and why they have not made the impact of the others.

In a career spanning 60 years, 584 paintings is not bad going, considering that hundreds were destroyed and that, when not painting, Bacon devoted considerable time and energy to booze, boys and blackjack. Indeed, in a period of less than 45 years, Velazquez produced an estimated 120 paintings, while Vermeer, in a lifetime of 43 years (and a career of around 25 years) famously only produced 35 paintings. Picasso, on the other hand, produced in excess of 50,000 artworks, of which 1885 are paintings, in a career spanning 82 years. Of course, times for Bacon were different from how they were for Velazquez or Vermeer, and Bacon’s work is of an entirely different kind from Picasso’s. So 584 is a respectable number of paintings for a man who was so often preoccupied with anything but painting. If only, one wonders, he spent less time roaming the streets of Soho looking for the ‘Nietzsche of the football team’ he might have produced more, like the solitary and reserved Rothko who managed 798 paintings in 46 years.

The greatest hits of Bacon, iconic, masterful and beguiling as they are, conceal 404 other works that have the potential to augment his reputation. There are surely some duds in there, but there are probably also some undiscovered treasures. Some of Bacon’s great works are his portraits of van Gogh, depicted on country roads and in brown fields as a weary, haggard scream of a figure. Although fairly well known, certainly by scholars, these works are, in public consciousness, secondary to the popes and portraits we know so well. Also fascinating is a particular seascape currently on show at Ordovas, which contains a familiar Bacon figure in the middle of an unfamiliar ocean view painted in luscious Prussian blue. Somewhere within the catalogue raisonne there must surely be more works like these that simultaneously proffer the familiar magic of Bacon while challenging the orthodox view with a nuance of style, a change of subject or an inflection of atmosphere with which we are unfamiliar.

It is not an accident that we only know a fifth of the extant Bacons. It is a trick of history that an artist becomes known for a small proportion of their work, for the present can only convert a lifetime into an ellipsis which must constantly contain the same small sample of output. If you think of all the Pollocks you have ever seen, you can probably times that number by ten to get at the quantity of drip paintings he actually made, and that is because we simply could not handle the enormity of his output so. After all, we are aghast in the present at Hirst’s manufacturing project, so we deny that all artists realistically manufacture on a mass scale because we have the historical illusion of their popular cannon. Indeed Hirst has produced considerably less than half of what Picasso did and production has been slowing at such a rate that it seems doubtful he will ever make as much as Picasso did. But nobody would dare think of Picasso as a soulless manufacturer as they do Hirst.

Bacon produced probably just the right amount, so it is a travesty that we are acquainted with so little of it, which is due in no small part to the market that circulates before our eyes like juggling balls the same representative sample which is echoed in the museums and textbooks. The market is a machine of confirmation bias, since it never throws up an unusual or non-standard Bacon, or anything else for that matter. The catalogue is set to demonstrate that the slice of Bacon we have gorged on has been woefully meagre. All we have ever had is a pound of Bacon’s flesh, which has been sumptuous, but he was a fulsome, complex man and now it is time to unfurl the rest.

Words: Daniel Barnes