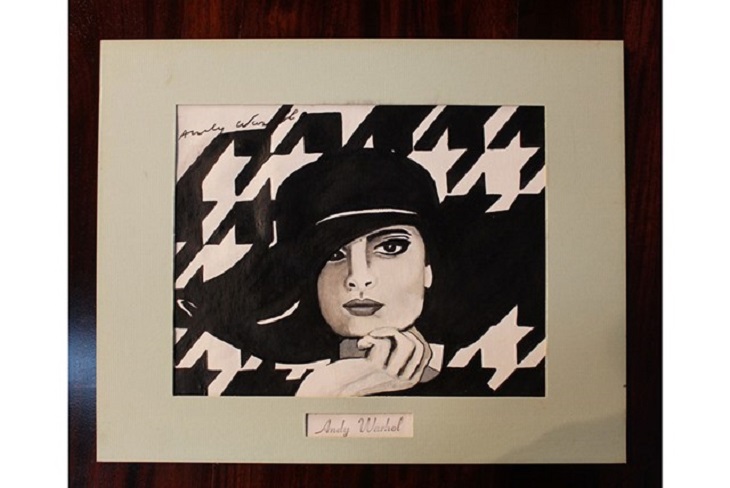

An auction house in Mississippi has sold a rare early Warhol for $247,000. The portrait of fashion designer Coco Chanel, thought to be from the 1970s, came from an unnamed Dallas collector who bought it from Jack Hamilton Gallery, Canada, in 1985. But there are good reasons to think that the painting is not a genuine Warhol.

Stevens auction house, which primarily deals in antiques (that’s the first alarm bell), originally gave the work an estimate of $50,000 to $2million (and there’s the second alarm bell). Despite having a stamp of authenticity from the Warhol Foundation on the back, Tom Sokolowski, former director of the Andy Warhol Museum, said ‘there is nothing about this work that bespeaks Andy Warhol in the slightest’. And, he continues, ‘how the authentication committee could have stamped it as authentic is just beyond any sentient person’s imagination’, (the third alarm bell). The stamp could be forged, or could have been given in error – neither of which are either impossible or unlikely.

Stevens claims it had the work examined by numerous experts, all of whom agreed it is a genuine Warhol, but for an auction house that has no particular specialism in art, let alone modern and contemporary art, to make a judgement so at odds with the opinions of Warhol experts is concerning. The company president, Dwight Stevens, said his consultants guessed at the work’s authenticity in the absence of hard evidence. Stevens clearly has not even the faintest notion of the science of authentication, which hinges these days on somewhat more than mere guessing. This is rendered all the more ludicrous when they knew of the work’s provenance so could at least have traced it back to the Jack Hamilton Gallery for documentation and a second opinion. Anyone can look at a painting and guess, and for that very reason we have experts – historians, forensic specialists, critics, dealers – as well as documentation and tests. Guessing at authenticity is basically superstitious, more on a par with the anointment of holy relics than with rigours scientific investigation.

Then there is the matter of the absurdly broad estimate. An auction house which knows what it is dealing with and is confident of its authenticity is able to predict the likely fluctuations of its market to within a few thousand. The house knows what it is selling and to whom it is likely to be selling, so an estimate that covers a margin of $1,950,000 is unheard of and a sure sign of ignorance, incompetence or sheer madness. Moreover, Warhols are not rare commodities: if you think you have a Warhol to sell, you can gather widely available data on similar works, prices, buyers and sales records in order to gauge an accurate estimate with the result that, if you’re worth even half your salary, most of the time you’ll be right on the button.

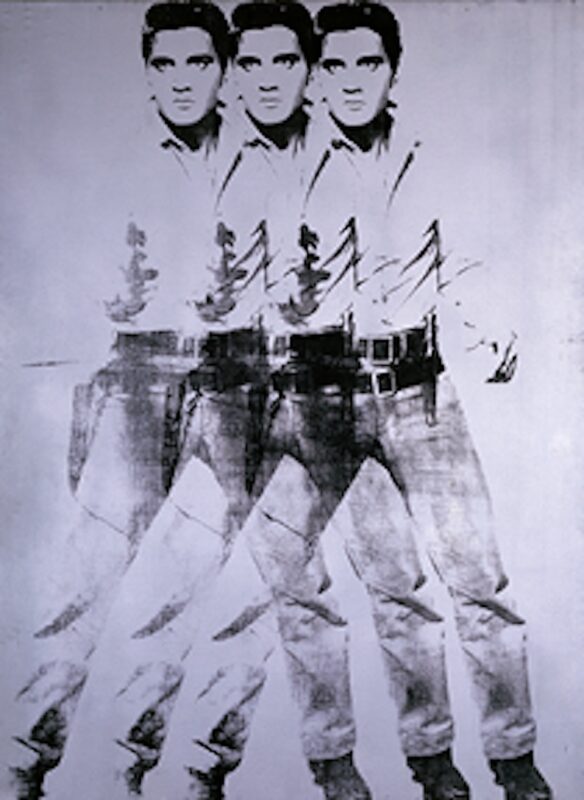

The fact that Sokolowski, as well as renowned Warhol expert Blake Gopnik, cannot see the Warholian nature of the work that Stevens could see is deeply worrying. After all, these people have seen hundreds, probably thousands, of Warhols, which is enough to know one almost instantly when you see it. It is a function of that near subconscious, but amazingly efficacious, phenomenon that Malcolm Gladwell calls ‘thin slicing’ – the ability to detect something essential in a miniscule snatch of experience. Of course, there may be Warhols that don’t look like Warhols, but those are the ones to which we pay very close attention indeed; those are the ones that are analysed, examined, compared, contrasted and researched to within an inch of certainty. They are not the ones that have a loopy estimate slapped on them and pushed on to the block without a moment’s hesitation.

The deeper mystery here is that the Warhol Foundation no longer authenticates artworks, since it shut down the Committee in 2011. This means that this work, and who knows how many others in the same positon, are subject to rash guesses. It is then up to the anonymous buyer of this work, who has as much to lose in reputation as they do to gain in money, to go to the very great expense of enlisting the services of the world’s experts. That may or may not happen, so in the mean time we have to just look – and if we do that, we see that this is the most Un-Warhol Warhol painting ever, suggesting even to the most casually educated eye that it cannot be genuine.

But the philosopher Nelson Goodman made the astute point that forgery – and by extension all questions of authenticity – works precisely because you cannot discern authenticity by merely looking since it inheres somewhere beyond the perceptual plane. And for that very reason, while we can all agree that this doesn’t look like a Warhol, a great deal more investigation is needed to tell us whether that is the case or whether a radical new Warhol has come to light. Visual art is, after all, partly about looking, but the really interesting stuff goes on in the far reaches of the mind and history where the eye cannot see.

Words: Daniel Barnes