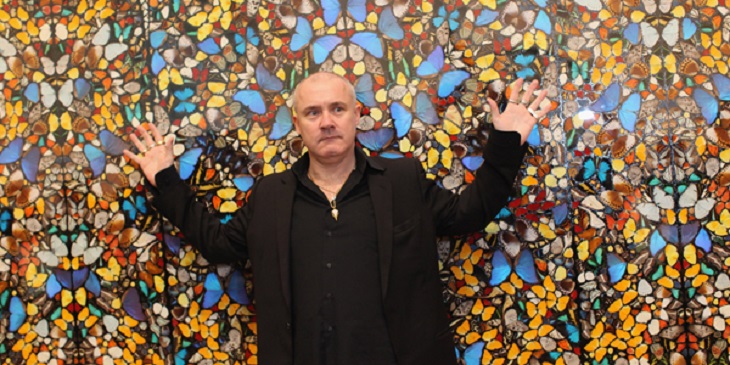

Damien Hirst posing innocently in front of his work ‘Doorways to the Kingdom of Heaven’, Tate Modern, 2012

Back in the 90s, while Alex James was busy spending £1million on cocaine and champagne, the YBAs got extremely rich selling shocking new art to an insatiable art market. As we all looked on, trying not to be sick again, the art sold for ever more astronomical prices well into the 21st century. This unspeakable euphoria fuelled ever more excess and ever more art, bolstered by toxic debt and the mantra that things can only get better. It is only now, as the young British artists are fumbling into middle age, that the pay me girl has finally had enough of the bleeps, so as she takes a bus into the country, it’s time to write the obituary of young British art.

Those heady days when Keith Allen would do anything for £5000 and goat came to a climatic end in 2007. It all came crashing down when Damien Hirst covered a platinum cast of a human skull in 8601 diamonds and sold it for £50million. Everyone gasped and cringed as Kirsty Wark asked him if he thought there was anything obscene about that. Damien bit his lip and the tumble weed tumbled. ‘Hopefully’, he said, ‘it’s not about money’. But of course, as he would later admit in an interview with Tim Marlow, it was all about money; it was about how much money you could throw at death. But it was also about how much money you could throw at art until art died.

And that’s how it happened: the most hopelessly ostentatious artwork became the most expensive piece ever sold by a living artist, and there was no longer anything more the YBAs could do to shock, sensationalise or scandalise. That diamond skull was the last and highest parting with the 90s. The fact that the YBA phenomenon is dead does not mean that it is irrelevant, for it was and remains the most important thing to happen to British art in 50 years. It only means that the dream is over and we have to now take stock of what happened.

Wark and Hirst: ‘£14million pounds worth of diamonds and platinum. Is there anything in your mind that thinks there’s something obscene about that?’

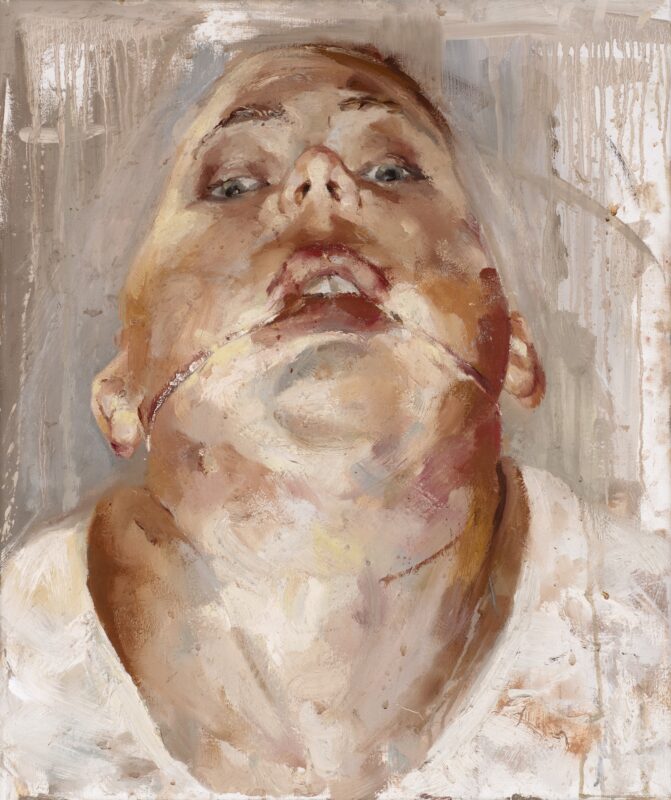

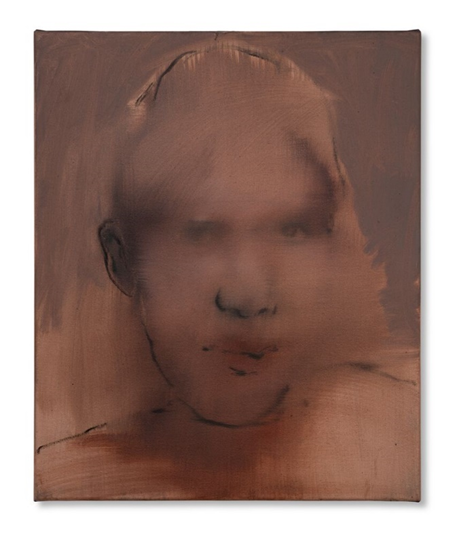

Despite the death of the YBA movement, its zombies still walk the Earth with varying degrees of success. Some of the artists, like Marcus Harvey and Mat Collishaw have continued respectable careers by fading quietly into the background, while others, like Gary Hume and Marc Quinn, linger in the middle-distance with an unfathomable faith in their winning formula. Michael Landy and Chris Ofili continue to surprise with nuanced changes of direction, while Jenny Saville and Fiona Rae are quietly, consistently good. Sam Taylor-Johnson has found a new career in film directing and the art she makes now is a far cry from the shock and awe of her youth. Even Tracey Emin has matured somewhat in style and form, if not in content, proving that it is time to grow up, even if a lonely Gavin Turk is still signing his name on eggs at the Art Car Boot Fair.

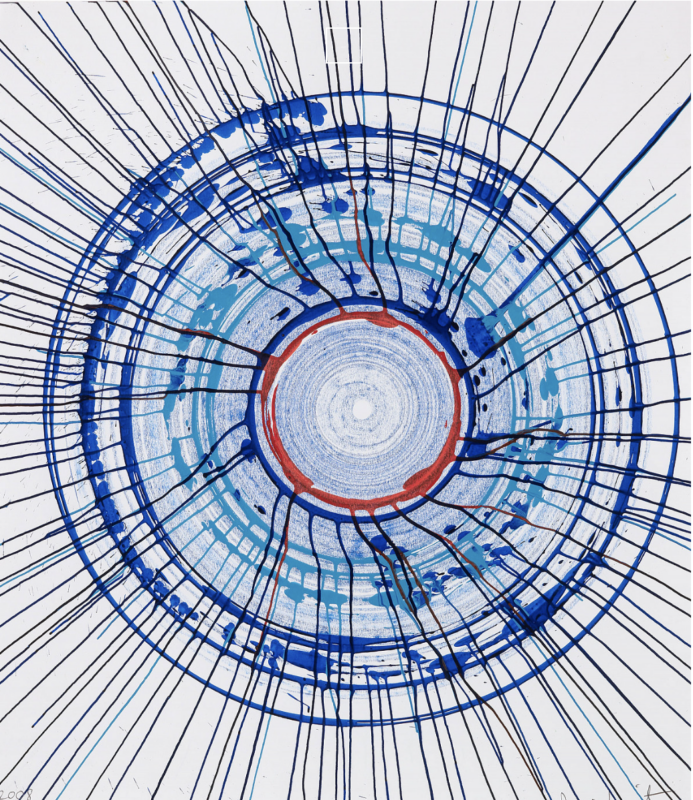

But sometimes one of them pops up as if nothing has changed, as when Jake and Dinos wheel out another round of Nazis or when Rachel Whiteread casts another banal object. The paradox is that it’s difficult not to feel a tinge of delight in front of a carefully doctored Hitler watercolour or a concrete mattress, but as the aesthetic high quickly fades the rot of repetition sets in. You can say a lot about Damien, but not that he makes it known every time he makes a new Spot Painting, for he only shouts when he’s had a new idea, which is pretty much every exhibition since 2007.

The 90s got the art it deserved, but when they keep doing the same things in a world which is so different from when they started, it looks archaic and awkward. This is typified by Sarah Lucas’ British Pavilion at Venice: as Sarah Lucas work it is great and the phalluses have not suffered brewer’s droop, but as art to represent Britain on the international stage it looks tired, as if we’re stuck in the 90s. As we watch Lucas beam with pride in the front of the world’s press, it is difficult to blame her for just doing her shtick, but it was misguided of the British Council to allow the world this antiquated view of British art.

Meanwhile, tired of reading Balzac and knocking back Prozac in Devon, Damien is building a mausoleum to the excess of his glory days – a museum in Vauxhall that will house his art collection, bought with all the gold he didn’t splurge in the Groucho Club. The best days are over and now it’s time to display the loot, like some imperial place of the King of Contemporary Art. And then there’s Charles Saatchi, whose influence began to erode as he started selling of his YBA treasures: he was forced, as a result of a protracted dispute, to sell his Hirst’s back to Damien, and then he sold his seminal Emins. Try as he might, nothing he could buy after that would reassert his power as chief tastemaker, save a few Christian Rosas, which is nothing to be proud of. Saatchi, once the prime mover, is now the shadow of a man who knows his Claret from his Beaujolais.

Installation view of the Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts 1997

One of the surest signs that the dream is over is the fact that the art bubble is no longer propelled by the YBAs, whose prices have quietly plateaued. The sale of Damien’s Lullaby, Winter for just £3million earlier this year is a grim reminder of the fact that back in the day it would have fetched £5-7million in a heartbeat. It’s time to move on. Not for those who are still enjoying the art or for those of us who are writing the history, for art is, in the end, only cultural history to be treasured. But for the artists whose reputations hang in the balance between artistic dignity and historic infamy. That doesn’t mean we don’t want to hear from them, only that we don’t want to hear the same songs again as if there’s no other way.

There is of course art after the YBAs, even though much of it pales by comparison, but that is what we have to live with. It’s time to kiss their dry lips as we say ‘good night, it’s the end of a century’. The YBAs have the eternal credit of making British art international and stoking a furnace which powered both public interest in contemporary art and a voracious art market. But the glory days are gone, and any attempt, sincerely nostalgic or otherwise, to recapture them looks foolhardy. The YBAs are now echoes from the past, ciphers of a chemical world where it was very, very cheap.

Words: Daniel Barnes