Lucian Freud, in bed with Kate Moss

A collection of Lucian Freud’s letters is to go on sale at Sotheby’s on 2nd July with an estimate of up £42,000. The letters were written to the poet, thirteen years his senior, Stephen Spender, while Freud was studying at the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing between 1939 and 1942. Such is the affection between the two men, it has been thought that they were engaged in a homosexual relationship.

It is well known that Freud could resist the pleasures of the flesh as scarcely as he could resist painting. If he had been in his prime now, he would be the subject of relentless media frenzy, but his golden years took place in a more private time. In addition to two marriages, Freud slept with fifty women later in life, although this seems like a conservative estimate, producing no less than fourteen children. It is also known that he had the occasional fling with a man or two. Indeed, Freud’s legendary promiscuity makes a nonsense of any attempt to codify his behaviour according to norms of either society or sexuality, with the best effort at classification simply being that he was a very horny boy. It is therefore possible, although by no means likely, that Freud was shtupping Spender.

Spender’s role in all this is much less vague – or perhaps just more clearly documented – insofar as his predilection for the boys is crystallised in his relationship with Tony Hyndman, whom he met in 1933 and was involved with until 1936. During this time, however, he had an affair with a woman, Muriel Gardiner, writing to his friend Christopher Isherwood, ‘I find boys much more attractive…but I find the sexual act with a woman much more satisfying’. Nonetheless, after a brief marriage to another woman, Spender eventually married the concert pianist Natasha Litvin, which last until his death 54 years later.

On the face of it, then, it is possible that Freud and Spender were involved in a relationship, given that both slept around a bit without much concern for the boundaries of sexual orientation. But before we get all over excited about this new gay angle to Freud we should consider both a disparity between the two characters and a facet of the times in which they were living.

Firstly, the historical facts suggest that Spender was markedly more gay than Freud, who really just seemed to like sticking his dick in things to pass the time in between paintings. Spender, on the other hand, expressed a genuine desire to seek male company and was noticeably torn in his desires for men and women. There is nowhere in the Freud archive such an emotional or psychological awareness – not least a struggle – of a conflict of interest between the male and the female body. There is just unabashed philandering.

Secondly, in 1930s/40s England there was not such a rounded, defined or socially accepted concept of homosexuality into which we can slot either of these two men. In a society in which homosexual acts are illegal, the church still has great sway and social attitudes are generally barbaric in comparison to the freedom we enjoy today, people were not divided into streamline categories of gay and straight, with or without prejudice. At best, homosexual was a category that denoted something that could be, and should be, corrected or cured, rather than the denotation of a group of equal human beings who happen to do some things differently from some other people. There was, in short, none of this singing about girls who do boys like they’re girls who do girls like they’re boys uncertainty, but only the right way of doing things and the forbidden way.

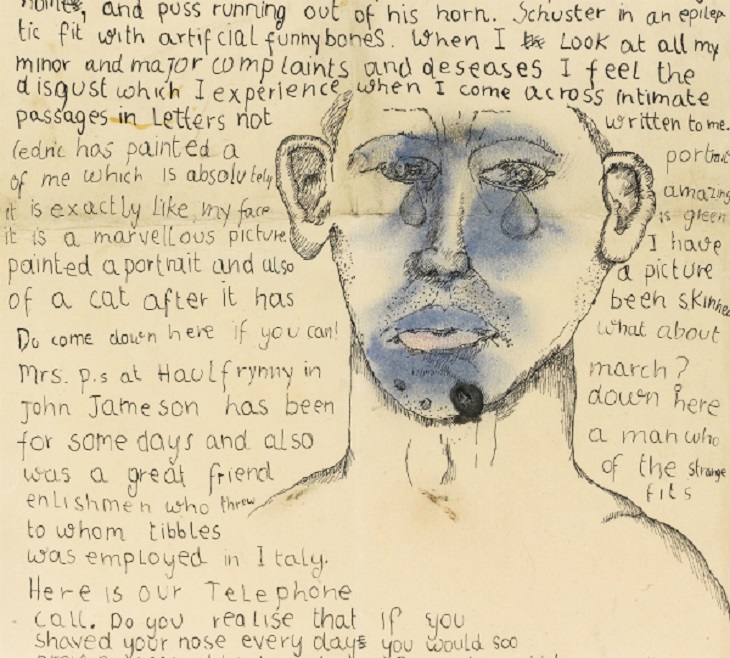

One of Freud’s letters to Stephen Spender

Add to the mix two further facts, and we have ourselves a rather delicious mystery. One, Spender’s son, Matthew, says ‘Lucian, especially as a young man, was exactly the kind of young man my father would be incredibly attracted to’. Shut out the noise from the fact that we are talking here about an older man and a teenage boy, there is nothing to say his affections were reciprocated. However, Freud’s teenage years are a notorious blackspot in his biography and it is now thought this is perhaps why. And two, it is said that Spender’s homosexual escapades ended with his second marriage, which took place in 1941, right in the middle of the period in which he was writing the letters to Freud.

We have here the makings of a sensational headline so oblique that it comes to almost nothing: a dude who occasionally liked dudes wrote some letters to a dude who very occasionally liked dudes, suggesting that perhaps these two dudes liked and knew each other in the biblical sense. Or an established poet befriended a fledgling painter in the misty fog of wartime Britain and they wrote some tender letters to one another. Either way, we have a faint glimmer of another side to Lucian Freud in these letters, which, in all honesty will do less to contextualise his painting than they will to muddy the waters further. And that, for a painter of such profound complexity, is precisely as it should be.

Words: Daniel Barnes