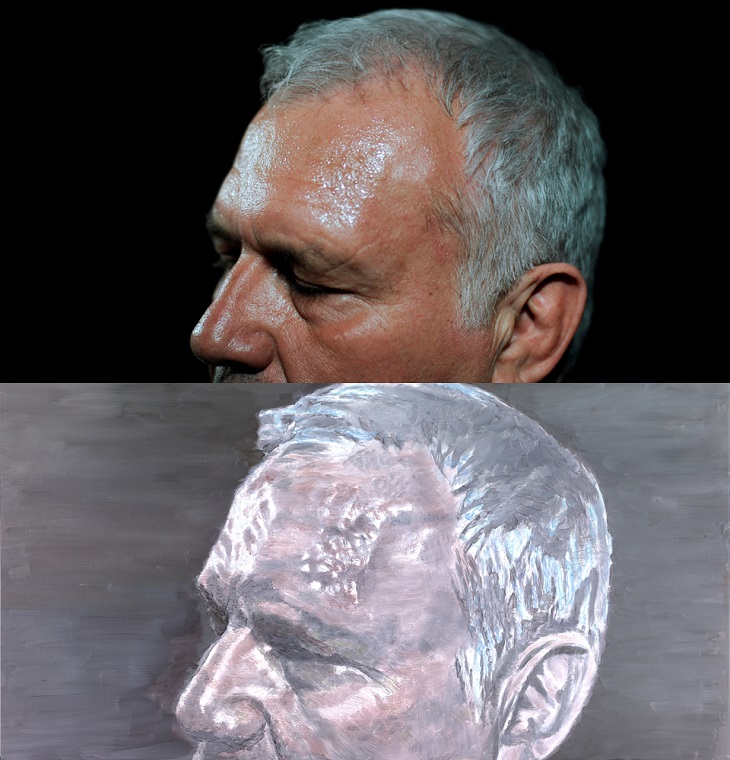

Above: Katrijin’s photograph of Jean-Marie Dedecker (c) 2010. Below: Luc Tuymans’ painting of a Belgian politician (c) Luc Tuymans/David Zwirner 2015

In January this year, a Belgian court found Luc Tuymans guilty of plagiarism for using a photograph as the source of a painting. It is his usual practice, not to mention the standard practice of artists everywhere, to appropriate source material from other artists. Now a new copyright law threatens to criminalise artists using pre-existing images and even museums reproducing them. Nothing in the practice of art has changed, but intellectual property has become more precious, undoubtedly for the worse.

Tuymans’ picture, A Belgian Politician, is both a portrait of the right-wing politician, Jean-Marie Dedecker, and a painting of the photograph by Katrijin Van Giel taken for the Belgian newspaper De Standaard. In a superficial way that should be irrelevant to the debate about the difference between a pre-existing photograph and a painting, the two are similar: the subject is depicted in the same pose, floating in empty space, with the same harsh cropping at the upper lip. But, as Adrian Searle lyrically argues, they differ dramatically: the surface of Tuymans’ picture is concerned with the touch of the painter’s hand, it is to be read differently from a printed or digital image, and it shifts the nuances of light, colour and shade to alter the semantics of the image.

We have two distinct artefacts – artworks, if you like – but it just so happens that one takes the other as its point of reference, and ultimately its point of departure. This was enough for Katrijin Van Giel to claim that her copyright had been infringed. The court, just a few weeks before Tuymans opened a major show at David Zwirner London, rejected the defence’s claim that the painting was a parody and therefore fell under fair use. For the parody defence to work, the court had to find the painting amusing and significantly different from the original; although it may not be especially amusing, it is significantly different, but this had no effect. Tuymans will be fined €500,000 if he uses any more of Van Giel’s work and if he ever shows the painting again.

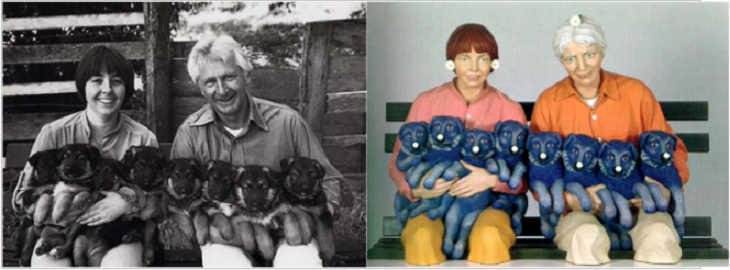

Appropriation of existing material as the basis for new works of art is nothing new. After Duchamp, it was open season and then we had Warhol’s Brillo Boxes. Artists have been doing it even before we gave it the name ‘intertextuality’ and subsumed it under the concept of postmodernism. What, then, went wrong for Tuymans? The same thing that has gone wrong for Jeff Koons so many times. In 1989, Koons was sued by Art Rogers for use of an image, found on a greeting card bought in an airport, of some puppies; Koons lost the case. In 2006, Koons produced a series of paintings based on a photograph by Andrea Blanch, but this time won. And again, in December 2014, Franck Davidovici filed a copyright infringement case against Koons for use of Davidovici’s advertising campaign for Naf-Naf clothing. So far the case has resulted in the work, Koons’ Fait d’Hive, being removed from his retrospective at the Pompidou. The case is expected to run in to millions of dollars.

Left: Art Rogers, ‘Puppies’ (c) 1985. Right: Jeff Koons, ‘String of Puppies’ (c) 1988.

Closer to home, the government has announced its intention, in 2020, to repeal Section 52 of the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988, which limits the rights on mass-produced items to 25 years. In real terms, this means that galleries, museums and publishers are going to have to relicense images used in books and on merchandise which, at the time of use were out of copyright but are suddenly going to be in copyright. This is going to make publishing more expensive and often unaffordable. Since it applies to designs of all natures, this means that artists who appropriate design property, such as Damien Hirst with his Hymn sculpture, are liable for copyright infringement. It is a stroke of wickedness on the lawmakers’ part that this includes ‘designs’ broadly construed, rather than mere images as in the case of Tuymans. Furthermore, the law makes copyright infringement of this kind a criminal rather than a civil offence.

Copyright law aims to protect intellectual property as the fruit of a person’s labour, their work and their source of income; it also aims to protect the interests of the deceased and their estates. The difficulty is that copyright exists for a noble and inalienable reason, but the imposition of it upon creative artists and cash-strapped museums for purely financial gain stifles rather than enhances cultural production and dissemination.

The case against Tuymans and the repeal of Section 52 are wrongheaded for two reasons. First, it is puerile to take exception to somebody else profiting from the use of your idea, when you yourself have doubtless done it to others and when in the 21st century this is the natural order of things. And second, it betrays a fundamental misunderstanding (or, worse, rejection) of the entire intellectual tradition of postmodern, which has, like it or not, crystallised every facet of culture, politics and economics we now have. We need to accept both of these things, not as unwanted consequences of the cultural field, but as preconditions for there being any culture at all. And therefore we need to find a way of protecting intellectual property at the same time as making it available for fair use.

The Tuymans case demonstrates the depth of the misunderstanding when a court rules against not just one picture but an artist’s entire practice, method and body of work. Copyright is all well and good, but it is foolhardy and ugly to negate the work of one of the most important painters of the century or to obliterate museums ability to sell merchandise. The key to resolving the deadlock between art and the law here is to recognise that a painting and a photograph, or a painting and an image of it on a mug are radically, indubitably different things and as such must be viewed and understood in entirely discrete ways. These copyright cases obsess over the similarities, which are superficial and beside the point, but it is in the differences that the majestic beast of an enriching and productive culture resides.

Words: Daniel Barnes