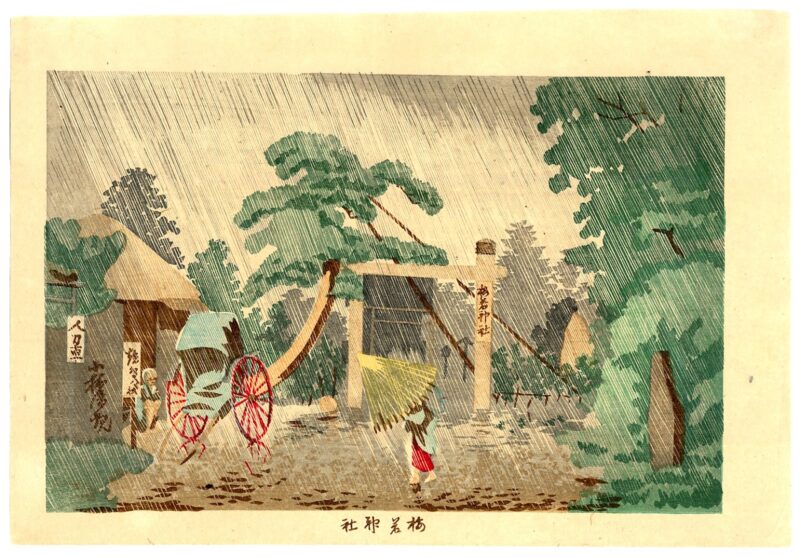

The Performance Space, with beer glasses. Photo: George Darrell for White Cube

Christian Marclay has just opened his first UK solo show since 2010’s The Clock. It looks like a major exhibition in a massive commercial gallery with nothing to sell, as if he has tricked White Cube into doing something for the love of art alone. Recent developments suggest a quietly burgeoning trend towards making a greater effort to conceal commercial interests behind a veneer of pure art in the form of performance.

The exhibition involves the world’s first mobile vinyl pressing unit, stationed in the gallery within a shipping container, managed by The Vinyl Factory. Every Saturday there will be performances by top composers and sound artists, at Marclay’s invitation, while on Sundays the London Sinfonietta will perform. Visitors will be able to watch while recordings of these performances are made into records, for sale in the bookshop in an edition of 500, with sleeves printed live on site by Coriander Studio. There are also some paintings, energetic hybrids of Pop art and abstract expressionism, of onomatopoeic words from comic books and an immersive 360 degree animation film. The centrepiece consists of eleven projections along the gallery’s corridor, which show Marclay trudging through the detritus of Shoreditch on a Sunday morning, tapping bottles and glasses left behind by Saturday night revellers. It is strangely melodic, but ultimately rather sad.

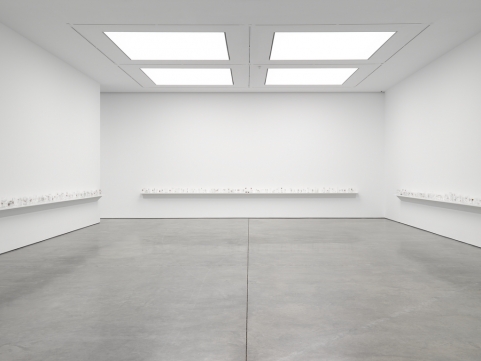

The show is a further investigation of Marclay’s trademark interest in the relationship between image and sound through the process and performance of music. But in its opening week, it is strangely inert, since it is only with the performances and the consequent vinyl pressing that the exhibition will be activated. Walking around the vast gallery space, you feel like an intruder on a film set where the action has ended and everyone has gone home. The show is the performance, without which there is very little to see.

There is even very little art, since the screen printing equipment, the stage and the vinyl pressing unit are there for a pragmatic purpose. Even the shelf of empty beer glasses that extends around the entire performance space is not a work of art, just contextual decoration or perhaps later a prop in the performance. It is interesting to see people behaving as if they are in an art gallery, in good faith, looking at the mixing desk, chairs, bundles of wires, vinyl-making machinery, buckets of ink and microphones as if they are artworks. This is the culmination of a hundred years of the readymade – we have been trained to be absolutely unable to tell the difference between art and the real world. Perhaps Baudrillard was right – the simulacrum is the truth.

The fact that there is currently little to see is a tantalising promise of what is to come, but the fact that Marclay appears to have so little to sell is more interesting. Of course, the gallery is going to make money, and of course Marclay has something to sell, but this is carefully concealed by the performance element. From Marclay’s point of view, it is clearly not about selling contemporary art objects; rather, it is about the immediacy of performance, public engagement, shared enjoyment and the pure pleasure of aesthetics unadulterated by commerce. The fascinating, and surely accidental, conceit in all this is that on the one hand, we have a simulation of art in the public display of ‘readymade’ elements which are themselves mere utilitarian accessories, and on the other hand, a blithe attempt to eschew the very concept of the commercial gallery as purveyor of objects – there is no art here, but pure performance of the idea of art, and then a performance that is art. Clever.

This appearance of pure art, carefully constructed and managed as it is by the very best in the business, makes art seems important again because it really does not look at all like the commodity to which we are so accustomed to seeing in our galleries. Art suddenly seems vital, spontaneous, passionate and necessary because it comes from the heart of the artists, rather than the misplaced loins of a collector. It is almost as if the gallery is staging a performance of the idea of art itself: playing art as cultural phenomenon for free public consumption, as something to be enjoyed and to edify the weary soul. It feels fresh, rejuvenating.

There are glimmers of the same phenomenon across town at the moment. Darren Bader is currently crowdfunding to raise £310,786 in time for Christie’s Post-War and Contemporary Art day auction on 12th February. The artwork will be the amount raised and will be sold to the highest bidder. By selling money as art Bader is making a statement about the art market, but he is doing it in the form of a convoluted performance that nonetheless plays in to the hands of the auction house, who will receive their feels accordingly. Gagosian’s monumental Richard Serra exhibition, which has been going on since October, looks like a museum show and by its very scale defies any possibility that someone would buy something so gargantuan. They both look strangely more like art than like capitalism even though that’s all they are. Again, the idea of art is being performed for the entertainment of the masses.

By returning to the pure idea of art as universally available aesthetic phenomenon – an idea we’d begun to suspect is only a romantic myth – perhaps the artworld is responding to recent reports that art market bubble is nowhere near bursting. Art, no matter how sincere artists may be, cannot remain credible in a world where the market is so big that cultural value has been consumed by economic value. Jeff Koons’ balloon dogs do not look like art, they glitter with the delight of tax evasion and are solid as a dollar. Art doesn’t look like art anymore because we cannot see it apart from the context of money, but a convincing performance of art might just be enough to reignite the fire that once drove men like Marclay to greatness.

Words: Daniel Barnes