Snoop Dogg at work in the Happy Socks promo film

Snoop Dogg at work in the Happy Socks promo film

It all started when Snoop was staying at the Palazzo Versace hotel, where a Versace cushion was the inspiration for a painting that would later sell on eBay for $10,200. Looking at the painting, one rather wishes he had opted to paint it black. This was the start of a love affair with painting that transcended the much-lauded expressive powers of music. It is an act of heartbreaking desperation: now all Snoop Dogg’s fantasies of becoming Snoop Doig have come flailing around in swirls of paint.

The stroke of genius came when Swedish sock giants, Happy Socks, commissioned Snoop to design a range based on his abstract paintings. The promotional video shows a half-naked Snoop, stoned and surrounded by female assistants, making light work of a number of canvases. It will go down in history as one of the great insights into a master painter’s mysterious creative process, alongside Hans Namuth’s film of Jackson Pollock. Here we see Snoop intoxicated with the Dionysian spirit, bringing Apollonian order to his fevered emotions. Great gestures of wild abandon that, with the lights out, would be dangerous, but in the luminous glow of the studio produce affecting works of art.

The paintings trace the way the hand expresses in purely visual terms the yearnings of the soul. It is crushing to think that for years and years Snoop roamed the rocky terrain of music with this hollow feeling that grows and grows until he’s sure there must be something more. Snoop explains the visceral immediacy of these works: ‘sometimes the music in my life don’t explain exactly what I’m going through, so [painting] is another piece of the puzzle’. Snoop could have done anything to fill this gaping hole in his life; he could have gone to Las Vegas or Monaco to win a fortune in a game or he could have walked five hundred miles, but he turned to the hallowed art of painting. Art, it seems, is the next best refuge for beleaguered celebrities, after Scientology and cocaine.

It is not that celebrities have a bad romance with music, but that the very act of making art affords a catharsis they cannot find elsewhere. You only have to look at the calm on Snoop’s face as he attacks the canvas to see that painting has relieved him of a pain that would make a shy bald Buddhist reflect and plan a mass murder. Art, as we know, saves lives – imagine what would have happened to the young hooligan from Leeds if a wayward fly had not incongruously landed itself on a freshly primed canvas. The problem is that, even though it has the discrete charm of a second-order simulation of art, what Snoop is doing is not art at all.

It is obscene to say that art is a subjective concept so that if Snoop thinks he is making art then he is, since this does nothing to distinguish art from anything else, which contradicts the fact that we think of art as somehow distinct. Moreover, the fact that we can scarcely agree on a definition of art does not prove that there is not one. The distinctness of art is not found in the peculiar qualities of the things we call artworks, but nor is it in the arbitrary subjectivity of a given observer. It is located in a network of practices which are enacted by a group of players that Snoop stands outside of.

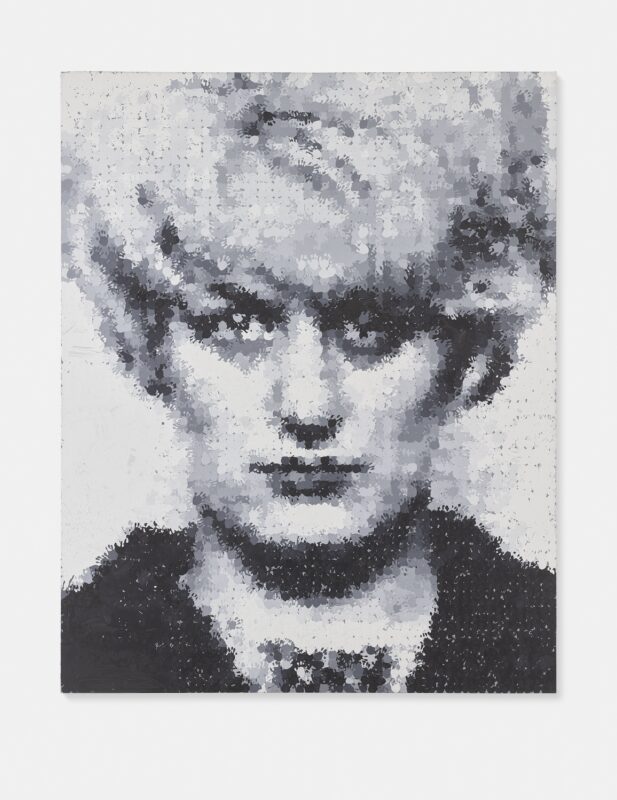

Snoop’s Versace inspired painting

Snoop’s Versace inspired painting

There is a sense that we tacitly agree on a fluid but operationally sufficient definition of art that has its philosophical origins in Arthur Danto and George Dickie. This is the view that ‘art’ is that which is produced within the artworld, which consists of artists, critics, gallerists, curators, museums, the market, art schools and the audience. If you’re reading this, then you’re probably in the artworld too. The institutions of the artworld are engaged in the legitimation of cultural products which, through discourse, determine the boundaries of art from the inside.

In Dickie’s version, artefacts are offered as ‘candidates for appreciation’ until the institutions confer on them the status of art; this is an organic process that occurs through the ordinary practice of art, much as one becomes the village idiot by simply being the idiot in the village. In Danto’s version, art is differentiated from mere things by the fact that it possesses an atmosphere of history and theory. This means that art can be perceptually indiscernible from mere things, except that it has an intellectual backdrop which is constructed by the institutions of the artworld. On this view, history and theory are the lens through which things are made and looked at, which is what makes them art; often people cannot see art when they encounter it because they are not looking through the lens of the artworld. The artworld, like all clubs, is something you have to be on the inside of in order to understand its products and practices.

It sounds circular to say that art is what is produced in the artworld, but as Dickie says, it is not viciously circular. As a matter of fact, it describes the way things are in reality. The point of it is to allow that whilst anything can be a work of art, not everything is; after all, hardly anyone – whether inside or outside the artworld – wants everything to be art. Art is that which is made within the artworld against a backdrop of history and theory, and which is defined, legitimated and judged by the discourse of the players in the artworld.

And so back to Snoop: he is not making art because he lacks the institutions of the artworld as the lens through which to see what he is doing, and nobody within those institutions is reciprocally legitimating what he is doing. It is, in the final analysis, the artworld that tells us that an unmade bed is a work of art rather than just an unmade bed. This act of transfiguration cannot be performed from the outside – those outside the artworld, especially the Daily Mail, cannot say what is and what is not art because they lack the requisite position in discourse. That’s Snoop in the corner with his paintbrush and that’s Snoop in the spotlight with his canvas. But if he is making art, then the artworld is losing its religion.

Words: Daniel Barnes