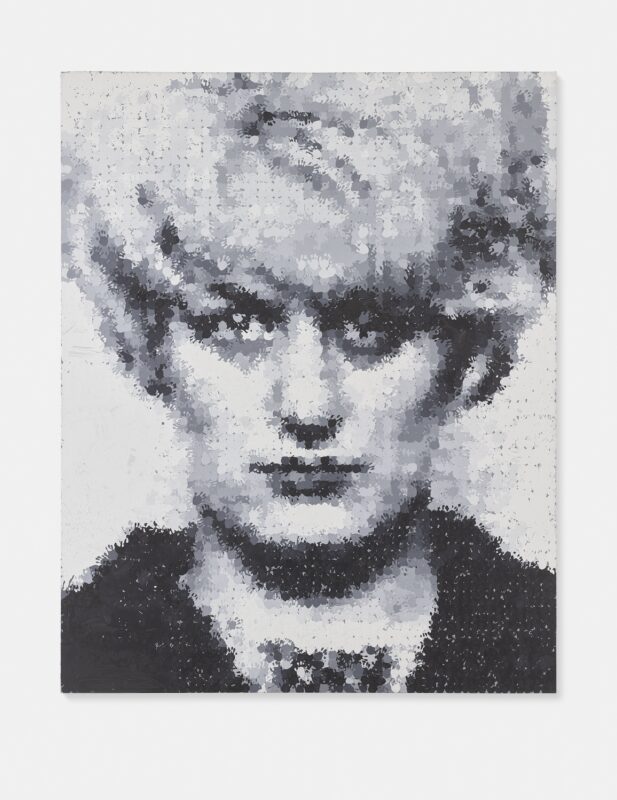

Miley Cyrus posing with some of her ‘art’

Miley Cyrus says her goal in life is ‘to not die a pop pop dumb dumb’. She is searching for redemption from a life lived in the spotlight: haunted by the ghost of Hannah Montana, plagued by a string of pop hits, cursed with a famous father and stupendous wealth, all played out through a haze of sex and drugs. So Cyrus has turned to art in order to save her soul, adding yet another chapter to the story of misguided celebrities searching for solace through art.

Cyrus has had a difficult year, after a stint in hospital and her dog dying, along with the gruelling schedule of her ongoing Bangerz tour. In the midst of all the chaos, she took time over the summer to reflect on the tumultuous events of 2014 and on her posterity, concluding that she would ‘freak out’ if she died only ever having been a trailblazing popstar. This introspection has now given rise to Cyrus’ big break into the artworld, with her debut exhibition, ‘Dirty Hippie’, opening last week at the offices of V Magazine, having premièred the day before during Jeremy Scott’s New York fashion week show.

It comes as no surprise that there are no surprises here, for Miley Cyrus makes exactly the sort of art you’d expect her to make: garish, clumsy, cheap, poppy sculptures that could only be the result of a petulant child’s spoiled indulgence. The sculptures are collages of found objects, including vibrators, teddy bears, beads, hamster toys, party hats and drug paraphernalia. These conglomerations of sickly sweet coloured plastic objects are reminiscent of Hello Kitty or the kind of tourist tat found in airport gift shops and Poundland. They are pristinely glued together to form phallic symbols, headdresses set upon pure white mannequin heads and bees-nest bundles of assorted detritus on plinths. They tread a line between abstraction and figuration, expressing a frustration with the shallowness of consumer culture, as if they are the fruits of an infant Jeff Koons’ untutored loins.

The story behind these sculptures is a gripping tale. A lot of the raw materials seem to have been donated by adoring fans or otherwise collected on tour by a popstar desperate to relieve herself of her abundant fortune. This accumulation of stuff inspired Cyrus to think about how money – and the things it can buy you – does not buy happiness. She reflected on how tortured her existence is, even despite the trappings of fame, and concluded that material possessions and adoration did nothing to cure the existential boredom she routinely dulls by smoking weed every day. Cyrus then started making art out of this clutter in order to both express her discontent with that clutter and in an attempt to create something more transcendent and durable than her pop career.

It sounds like a familiar story, the birth of art out of the spirit of discontent with consumerism and popular culture. Cyrus is following in an illustrious line, where comparisons could be drawn with the likes of Koons, Hirst and Richard Phillips. Like Phillips, this is art that aims to expose the emptiness beneath the sheen of celebrity; like Hirst, it uses a disparity between the materials and the ideas expressed in them to raise questions about value; and like Koons, the sheer banality of it all is overblown to the point that it is irresistible. Furthermore, the art of Miley Cyrus possesses the charming duality of being both an outward-looking critique of culture and an intimate expression of her tormented inner self. In any analysis, it is deliciously post-Empire.

Cyrus’ own explanation of her art is somewhat less poetic, but probably more honest. ‘They say money can’t buy happiness and it’s totally true…Money can buy you a bunch of shit to glue to a bunch of other shit that will make you happy, but…obviously the shit you buy doesn’t make you happier because I’m sitting here gluing a bunch of junk to stuff’. You almost feel sorry for her because, at the grand old age of 21, she is clearly having an existential crisis and she really has a clear sense that art is a perfectly logical response to it. But you don’t feel sorry for her because she is Miley Cyrus.

The works that comprise ‘Dirty Hippie’ certainly look like art. They are collaged sculptures, a fusion of the contemporary trend for upcycling found or appropriated materials with the traditional craft of sculpting. And they are expressive, in the manner of RG Collingwood’s injunction that art should arouse in its audience an emotional response to the artist’s state of mind as embodied in the work. Moreover, they also comment more broadly on the human condition in the grip of late capitalism.

There is a perversion in the public response to contemporary art insofar as when an actual, established artist presents a work that mildly offends out-dated sensibilities about what art is, there is an outrage which asks ‘Is it art?’. But when a celebrity, well-accomplished in some field of entertainment but with little artistic background, presents a work that minimally simulates the appearance of art, nobody bats an eyelid. When a high-profile event like the Turner Prize proffers Tracey Emin’s My Bed or Martin Creed’s The lights going on and off, a braying public concludes that this is not art. But when a self-indulgent celebrity with too much time on their hands convinces a gallery to show their artistic fumblings, such Miley Cyrus or Pete Docherty’s well-meant but ghastly blood letters, the public accepts it as both art and another glittering example of that celebrity’s genius.

The question of how to respond to Cyrus’ work, then, is rather complex given the willingness to accept celebrity art while rejecting genuine artworks, even if it is possible to speak of it in high-minded terms as if it is the finest of fine art. A fair, intellectually responsible judgement requires that we divorce the work from the person who created it, as if applying Rawls’ Veil of Ignorance. On this view, it looks like that kind of trendy, disposable commercial art that ticks all the right boxes to buy today and sell tomorrow, like a plastic Kassay. But this is charitable when you consider that celebrities like Cyrus have a large enough share of global attention without encroaching on the artworld so loudly. Consequently, it is impossible to ignore that Miley Cyrus has made a decent simulation of art, the charming illusion of which is sustained by an unfathomable self-belief. Nonetheless, if you want edifying contemporary art which does more than just look like art, then you could do better than the idling of a drugged-up, bored, pop pop dumb dumb.

Words: Daniel Barnes