As autumn descends on London, the artworld is gearing up for the great tragic-comic circus of consumption and gossip that is Frieze Art Fair. The official mythology of Frieze has it down as the biggest, most important fair in town and among the top notch artworld events on the surface of the globe. It’s like a farmer’s market crossed with the trading floor of a stock market, but with art and champagne and VIP rooms. It simultaneously stands for the victorious boom of the art market and for the soullessness of contemporary art’s fascination with anything other than art. With a month to go before the Big Top opens its doors, I want to send a message to the misguided people who are anti-Frieze.

The complaints are always the same. There is an unfathomable glut of stuff, most of it not very good and almost all of it produced for purely commercial purposes. The alarmingly happy marriage of art and capitalism, expressed in its purest form in art fair like Frieze, only highlights that art is the plaything of the super-rich. The dismal realisation that when money enters into art the intellectual prowess and aesthetic allure decrease accordingly. The terrifying illustration of the way in which a handful of artists and, more worryingly, a handful of galleries control not only the market, but the entire edifice of an otherwise varied and complex culture industry. And there is the undeniable sense that Frieze is much less about art than it is about spectacle, posturing, being seen and chortling sweet nothings over champagne.

None of this is untrue, of course, nor is it unfair. But if you dig a little into the furrowed brows of the anti-Frieze people you realise that this is not entirely the reason they dislike it. Indeed, it is only the bedrock of a much more urgent and personal problem which blocks their enjoyment of the fair.

I adore every ugly, money-soaked second of being in the midst of the high-octane drama of the fair; and I cannot consume enough rampant press coverage of everything that does or does not happen in and around it. The reason for this is that I stand gloriously dethatched from it. Nothing about my life stands or falls on Frieze, and this is true for the vast majority of anti-Frieze people.

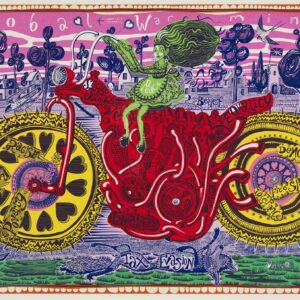

Far from inspiring abject despair and existential alienation, this detachment frees me up to enjoy the spectacle. The scale of the thing, for a start, is hilarious: row after row of stands peddling unintelligible luxury goods is like a supermarket clearance sale at the dawn of the apocalypse. As the last and highest statement of global capitalism, Frieze celebrates abundance over quality and drives the steak of inequality deeper into the heart of the artworld’s eternal vampire that is the poor, struggling creative. This would be insulting if it were not so ridiculously overblown and played out like some freakish costume drama in a language that nobody understands, with all the roles played by otherworldly freaks whose faces, like those of dog-owners, are inherited from the artworks they are oh-so-proud to own.

When you have nothing to gain and nothing to lose, this spectacle is great entertainment. As Jeff Koons unwittingly takes your photo while trying to capture a Chapman, or when four kids sitting inside the same black dress is an important work of art, you could cry if only it weren’t so outrageously funny that some people take this seriously and think something essential, ineffable and intimately life-changing hangs in the balance here. The whole thing is just too ludicrous to take seriously, and what you cannot take seriously you might as well just enjoy. It is for this very reason that I characterise the artworld – particularly the market – as a series of myths which ensure the smooth operation of unbelievable real-world processes: if you took it as cold, hard facts, then you would be apoplectic with despair, but as a series of myths it can be interpreted, shared, analysed, reinterpreted, enjoyed and perhaps even explained away. Either way, the facts are the facts, and this is the artworld and this is the market.

I love Frieze because I’m a sucker for a spectacle; showmanship and the postmodern capitalist circus impress me in purely aesthetic ways. But I am able to love it so because I don’t think anyone is going to see the glint of genius in my eye or overhear me regaling my companions with how Elmgreen & Dragset are going to save the post-Marxist intellectual left. I don’t think I have anything to gain but a good time; at most, complimentary champagne from the Hix bar and a cheeky smile from Jack Whitehall (who is both fatter and better looking than he is on TV).

The reality is, of course, that I do have a vested interest in Frieze insofar as I am an arts writer and it is part of my work to go there. But I don’t cling to this in order to desperately render meaningful the great absurd beast that is Frieze. The anti-Frieze people always seem to me disappointed because they want Frieze to be something other than it is; they want it to be their break, they want it to take them into its loving arms and cradle them into stardom, or they just want to see an earth-shattering work of art. But Frieze offers none of this, and nor is it meant to.

If you take the high-minded step of shunning the whole affair, then Frieze has won in carving divisions in a cultural sphere that really should be for everyone. So rather than take it all so seriously, go with the electric flow, let yourself be consumed by the spectacle, and smile gregariously at every ludicrous outfit and artwork you pass.

Words: Daniel Barnes