Most days art Critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train – though this week it was a plane back from the South of France. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?

Paralympics for art would make no real sense, so it’s rather perverse to ask ‘who painted best from a wheelchair?’ Naturally age can lead to frailty: Renoir and Matisse made iconic late works that way. More youthfully, Frida Kahlo’s last works before she died at 47 were made after losing a leg to gangrene, and Chuck Close has been confined to a wheelchair since 1988.

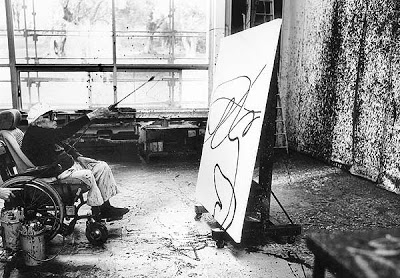

In some of those cases – notably Matisse’s cut-outs – physical limitations directly affect the type of work; and that’s true of the last years of the German-born, mostly French-dwelling Hans Hartung (1904-89). His unusual life included marrying Norwegian artist Anna-Eva Bergman both before and – having divorced in 1939 – after the Second World War, in which he lost a leg while fighting for the French Foreign Legion. Hartung’s studio is preserved on the hills above Antibes, along with various implements for applying paint: brooms, branches, forks, curry combs – and a garden spray attachment much-used during his last decade. That found Hartung, considerably aided by assistants, in ‘a trance-like state… partly induced by wine and an insulating barrier of Baroque music played extremely loud’*. Those many late works – e.g. 360 canvases in his 85th year! – have been considered of dubious status, but now the centrality of Hartung’s direction of events from the wheelchair tends to be recognised, however far from the vigorously mobile archetype of the heroic painter.

* from Jennifer Mundy’s excellent analysis of the late work at www.tate.org.uk/download/file

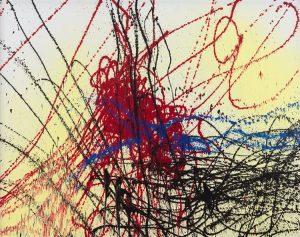

Hans Hartung: ‘T1989-E46’, 1989