David Dipré, ‘Head Piece’, Oil on Concrete.

David Dipré, ‘Head Piece’, Oil on Concrete.

‘Unknown Sitter DOS’ is curated by Covadonga Valdés. At Charlie Dutton, it runs through to July 20th 2013 (www.charlieduttongallery.com). The show includes an essay by Alex Veness featured in the on-line anthology ‘Knowing the Unknown Sitter’. Artists shown are Virginia Verran, Dallas Seitz, Galen Riley, Damien Meade, Cathy Lomax, Marcus Harvey, Kirsten Glass, David Dipré, Marianne Basualdo.

Review by Yvette Greslé

Inconspicuous in scale (and in a corner) an object that does not proclaim itself. It reminds me of masks that, via the colonial encounter, migrated into twentieth century painting. It suggests a use and a context, alive and animated, but it is constructed out of concrete. I project a human face: skin, eyes, nose, mouth and the shape of a head. Uneven lines, surfaces and marks – green, red, black, yellow – disguise and reveal the concrete, concealed below. I see bumps and dents and the textures a paintbrush makes when – in a single swoop, and thick with paint – a line is made. This is ‘Headpiece’ by David Dipré: a work that obfuscates painting and object and imagines the portrait as a three dimensional form. Embodied in the idea of a mask are themes of disguise, transformation and performance. The themes opened up by Dipré’s work are threaded through this exhibition: ‘Unknown Sitter DOS’, curated by Covadonga Valdés.

Valdés is also an artist (a painter), and it is always interesting to consider the relationship between an artist and curatorial practice. She grapples with portraiture a powerful presence in the history of art and visual representation. Portraiture is also a theme that (historically) exists in an intimate relationship to her own medium, painting. Portraiture is difficult to define, and the moment we think we have a grasp on its meaning it eludes us. It draws attention to the nuances of what it is to be human: historically portraits sought to embody the attributes of political power and social status. Self-portraits open up interior worlds, desires, emotions and states of being. Today portraits are devices through which to perform an identity or several. Artists exploring the relations between images and politics stage representations (of selves and others) that give a voice to the politically disenfranchised. Portraits can appear in two or three dimensions but are not simply about sculpture and painting. Mediums such as performance or video expand what a portrait can be and add the experiences produced by movement, sound, space and time. We are now accustomed to portraits that dissolve the identity of the sitter, that speak to the personality of the artist, or that attempt to erase the presence of both. Valdés comments: ‘In contemporary portrait painting the identity of the person being portrayed gets lost. In a way, this is through the personality of the painter. This show is about the sitter. Who is the sitter? Who is the sitter represented by?’

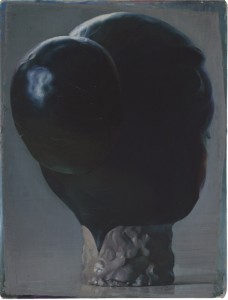

Damien Meade, ‘Untitled’, Oil on linen on board.

Damien Meade, ‘Untitled’, Oil on linen on board.

The event of sitting for a portrait suggests a time-space that speaks to process and the possibility of failure rather than finitude and completion: sketches, notes, props; and a figure not yet formed. Once a portrait is finished there is certain pathos to anonymity, to unknown sitters written out of memory. Damien Meade’s ‘Untitled’ embodies the sensations of not knowing: a blackened form open to projection suggests a kind of memento mori. At first, I see the back of a woman’s head and neck, an object detached from a body. I see hair bun, eyelash, lace collar, and then nothing but shapes. It/she, a presence within a mysterious space that suggests depth and flatness all at once: the edges of the picture are uneven allowing glimpses of a blue surface beneath.

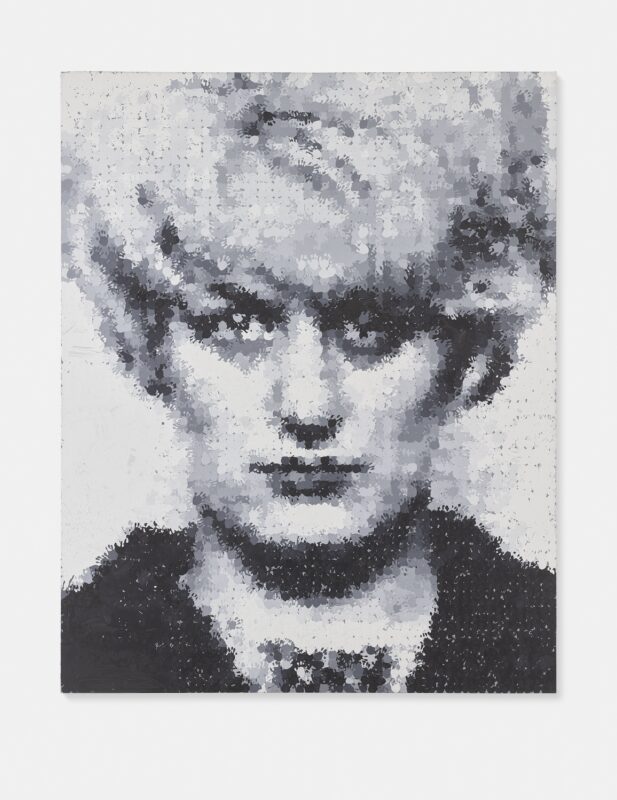

Marcus Harvey, ‘Old Man’, Ceramic.

Marcus Harvey, ‘Old Man’, Ceramic.

DOS performs, the curatorial statement tells us, as the disk operating system, and speaks (to me) of the advent of personal computers. Today technological advances have fundamentally altered the relationship to images, and access to them. Search engines present artists with a labyrinth of sources, spanning continents and centuries. Images from oil paintings on museum websites to stock images are circulated and re-cast. Marcus Harvey’s ‘Old Man’ speaks of how art historical and mass produced objects collide. ‘Old Man’ (he reminds of a jovial Bacchanalian character) is reminiscent of the mythological themes that over-populate the history of art, and popular culture. Rendered in ceramic, and wearing a gold Christmas cracker crown, Harvey plays with overlays of kitsch, mass production and art practices in dialogue with history. ‘Old Man’ is funny and irreverent while it makes me think about how it is I receive and consume images. I take pleasure in peering behind this sculpture of a figure that is a simulacrum of sorts: deliberately raw, and unfinished from the back, this object registers its own construction, and its imperfections. Cathy Lomax, ‘Gams’, Oil on card, vanity mirrors and mixed media.

Cathy Lomax, ‘Gams’, Oil on card, vanity mirrors and mixed media.

In the world we inhabit, ordinary people are instant celebrities. Identities can be forged, hidden or performed. Cathy Lomax’s ‘Gams’ perform the stock poses that dominate the history of women as consumers. Women’s legs and feet in white peep toe shoes strike the familiar ‘delicately feminine’ pose of 1950s advertising. Lomax’s exquisite painted miniatures (on folded cards) play with repetition, doubling, and reflection. They stand on a table surface which, in the shape of a flower, is constructed out of mirrors that reflect, multiply and displace. Galen Riley’s ‘Bone Dry’ begins with a visual history embedded in women’s bodies as sites of desire and consumption (her Uncle Bill’s porn collection is a source). She cuts, edits and reassembles porno imagery into an unsettling movable mass of re-constituted body parts of breasts, arms, legs, backsides and so forth. Galen Riley, ‘Bone Dry’, Printed matter on board with paper fasteners, 47 animates (200 parts).

Galen Riley, ‘Bone Dry’, Printed matter on board with paper fasteners, 47 animates (200 parts).

The idea of the unknown in the 21st century takes on meanings that are far from innocent or benign. But 21st century technologies, while opening up ethical questions about human subjects, representation and circulation, also require us to look further than ourselves and our own borders. ‘Ruby Slippers’ by Dallas Seitz consists of found Mexican border crossing shoes, and a Jose Cuervo tequila bottle: the shoes are worn by men, women and children who, trying to reach the United States, cover their feet with foam and carpet slippers to avoid leaving identifiable marks in the desert sand. These objects (absurd, tragic, and without a wearer) resists a gaze that presumes to know and define its sitter.

Dallas Seitz, ‘Ruby Slippers’, Mexican border crossing shoes made of foam, carpet and string. Jose Cuervo tequila bottle, MDF plinth.

Dallas Seitz, ‘Ruby Slippers’, Mexican border crossing shoes made of foam, carpet and string. Jose Cuervo tequila bottle, MDF plinth.

This is a subtle and complex exhibition that says something intriguing about the possibilities of curating small shows about big themes. These kinds of exhibitions present opportunities to think about visual worlds, and their histories, from the vantage-point of intimacy. They also present opportunities to engage the work of artists at different stages in their trajectories, and artists who choose to navigate the art world in different ways. It is interesting to think about the relationship (of the work selected) to the artist as curator. The artist is invested in the day to day process of making work: its isolation, its tensions, failures, experiments and possibilities. The act of curating is informed by critical distance, as much as by the subjectivity of the curator. Curating takes into account the history of art and criticism, and the meanings produced by visual relationships and juxtapositions.

Exhibition closes 20 July www.charlieduttongallery.com