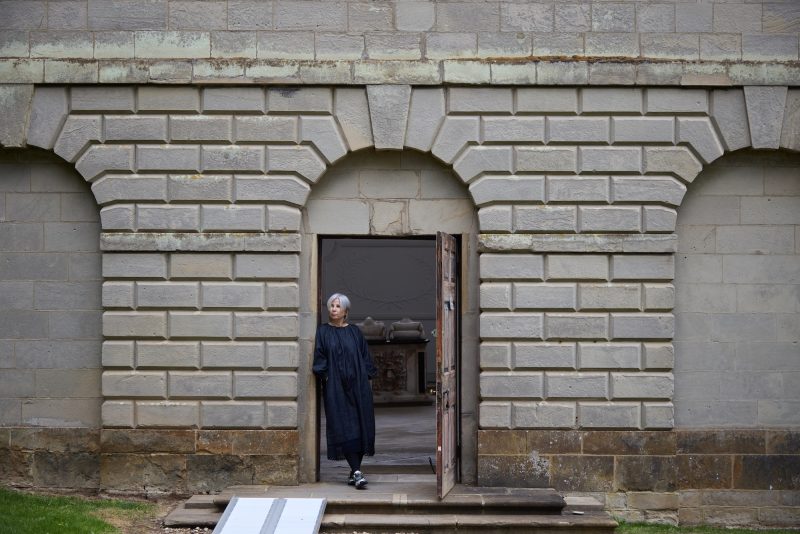

The Louvre-Lens Museum will showcase artworks from throughout history. Photograph: Pascal Rossignol/Reuters

So grim are the northern stereotypes still endured by the French former coalmining town of Lens that when fans of rival football team Paris Saint-Germain unfurled a banner at a match calling the locals “Paedophiles, unemployed and inbreds” it sparked a court case for hate speech.

But on Tuesday , the tiny, cash-strapped city of Lens – ravaged by the first world war, left struggling by the end of coalmining, best known for its red-brick terraces, slag heaps, football and love of chips – will celebrate the ultimate revenge for past injustices as it unveils France’s most important arts event of the decade.

The Louvre will open a striking new outpost on the site of an old Lens coal pit, transporting some of its top works to a glass structure in the midst of housing estates.

The Louvre is Paris’s biggest cultural attraction, one of the largest arts centres on the planet and the world’s most visited museum, attracting more than 8 million people a year. Its Lens outpost could transform the post-industrial north, with local politicians hailing it as a miracle.

The Louvre-Lens project is seen as far bolder than other famous museum satellites, the Guggenheim in Bilbao, Tate Liverpool or more recently the Pompidou centre in Metz, because those cities are larger, better established and better funded. Lens, with a population of around 35,000, does not even have its own cinema, boasts two modest hotels and only opened a tourist office at the end of the 1990s. At the entrance to the museum site sits not a showy restaurant, but a small terraced betting shop and tobacconist.

The initiative in a depressed mining region is an act of great political symbolism, marking a return to the revolutionary roots of the Louvre. Already the architecture is being hailed as a mastery of understated minimalism, perched on the site of an old pithead. The Japanese architects of the firm Sanaa said they didn’t want to create an “imposing fortress”. But the glass structure – described as “boats on a river delicately floating into a huddle” – boasts views of the giant slag heaps at Loos-en-Gohelle, the largest in Europe and recently graced with world heritage status.

The gallery layout is also a world first: 200 key works, from Greek sculpture to 19th century French painting, will not be separated by theme, style and era as is the norm, but be showcased together in one long gallery, uniting 55 centuries. Elsewhere, the temporary exhibition space is larger than that of the Louvre in Paris and begins with a Renaissance show including Leonardo Da Vinci’s newly restored The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, which will leave its Paris home for the first time in 200 years.

But Daniel Percheron, the socialist head of the Nord-Pas de Calais region, which funded over half of the €150m (£122m) cost of the museum, felt the most important piece was the transfer to Lens of one of the Louvre’s most famous paintings, Eugène Delacroix’s French revolutionary masterpiece, Liberty Guiding the People.

“When the Lens miners came up from the pits, covered in soot, they had two distractions, football and their racing pigeons; they would look up to the sky waiting for the pigeons to return from a race. It’s wrong to say there was a cultural void here, it was the miners who fought for rights, unions, pensions and healthcare.

“Their glory can be restored through this museum. There was a one in a million chance for the Louvre to come here. It’s an unimaginable dream. The miners built France, they symbolise France. This museum is all about restoring justice to this region.”

Local politicians hope it will take only 10 years for infrastructure and jobs to boom in an area that has almost double the national unemployment rate. The first move will be to build hotels if it is to have the impact of the Guggenheim in Bilbao on this post-industrial region. As well as a new young audience of locals and people who have “never set foot in a museum”, the Louvre-Lens hopes to attract the same visitors as its Paris palace, including British tourists.

Easy to get to from Kent by train, and near crucial first world war battlefield sites, the museum hopes for 700,000 visitors this year. Henri Loyrette, the head of the Louvre, stressed the Louvre-Lens “is not an annexe, it’s the Louvre itself”.

Xavier Dectot, director of the Louvre-Lens, said the aim was to bring “humanity” to the museum-going experience and to create “a spark of happiness” in a region already transforming itself. When President François Hollande opens the museum on Tuesday, the town will lay on a vast celebration and fireworks display at the football stadium, advertising unlimited chips.

But amid the festivities, the museum will not be spared the exacting demands of world art critics. Already, the mould-breaking idea of a chronological display of works from 3,500BC to the 19th century, bringing scores of civilisations and styles into one room, is being questioned.

Harry Bellet, deputy culture editor of Le Monde newspaper, hailed the museum as a “revolution in spirits” but he feared the long gallery filled with so many styles and eras risked looking “like a bookshop where all the books are muddled up”. As the Louvre-Lens will have no permanent collection but instead be renewed every five years, the museum will no doubt tweak its experience as it goes along.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.