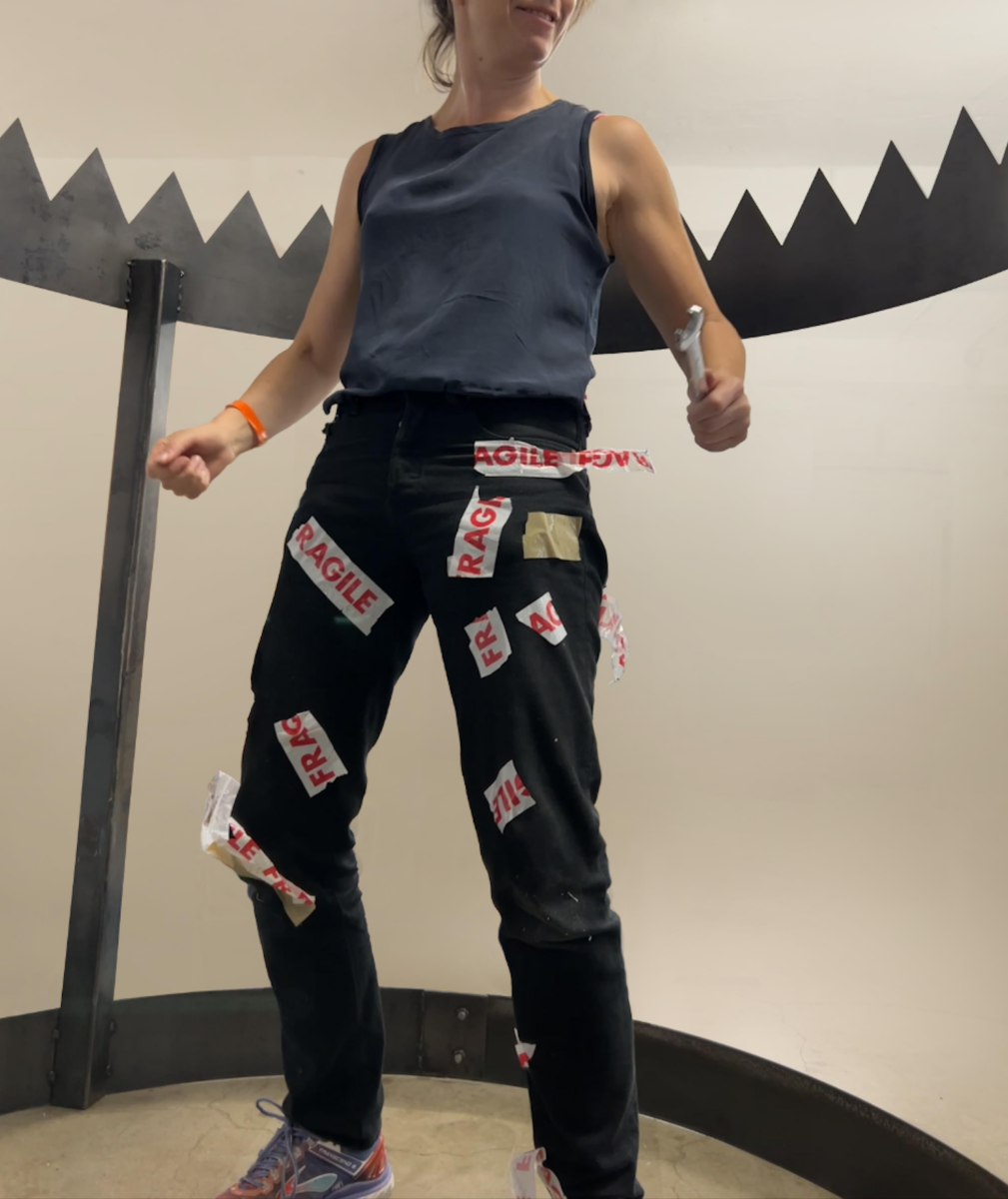

Doireann Gillan responds to a heightened sense of socio-political precarity by placing balloons stretched to their limit dangerously close to the sharp edges of metal structures. The tension of blunt saw blades forced into shape is palpable, the entire installation teetering on the edge of collapse.

The concept for this body of work was influenced by the idea of ‘Cruel Optimism’, a term coined by cultural theorist Lauren Berlant to describe the absurd attachment to fantasies of the good life while living within crisis, and the blow of discovering that the world can no longer sustain these.

The symbolic message of The Party’s Over couldn’t be any more relevant than in the immediate aftermath of the US elections. A big balloon of hope has just burst. Time to get real!

Doireann Gillan is a multidisciplinary artist whose practice follows the Irish tradition of blending beauty and humour with themes of struggle and loss. Investigating the triangulation of rage, restraint and resistance, her works are both symbols of joy and excitement and harbingers of loneliness and nostalgia.

Using sculptural forms that command space and push the limits of materials under duress, she presents a playful provocation to start taking risks and challenge established ideas of culture and behaviour.

Similarities with cracker crowns, colourful balloons and party favours are purely coincidental – or are they?

Doireann Gillan, 15th – 30th November 2024

The Bomb Factory, 99 Kingsway

About the artist

Doireann Gillan is an Irish multidisciplinary artist whose practice spans sculpture, video and performance. Her thesis Gag. Clench. Wail gained a distinction at the Royal College of Art in London.

Her key concerns are the examination of rage, restraint and revelry. Their practice draws upon the pervasive presence of tension in contemporary life – and the appeal, or lack thereof, of risk taking in an ever-shifting landscape.

Sculptures invite touch and interaction, while continuously testing boundaries. Much of the work exists in a state of structured tension, prompting one to wonder what might happen if a piece were to unfurl, snap or collapse. The potential to release a comedic charge in turn leads one to ask: can we feel more powerful by reclaiming pain in times of socio-political crisis. Or does it trivialise meaning?

Gillian’s practice further invites viewers to reclaim historically gendered emotions as unassailable social forces that require ongoing negotiation and reassessment.

Methods are playful yet rigorous.