The Brussels Antiques & Fine Arts Fair – BRAFA – was founded it 1956, making it the longest-running such event. This year’s 132-exhibitor fair is a typical mixture of antique, tribal, classic, modern and contemporary art and design. The many high-quality Belgian galleries – about a third of those present – are combined with a substantial international representation. Painting dominates the mainstream art category, as is reflected in the following selection of ten artworks of interest, with a bias towards the unusual, whether surreally so or otherwise:

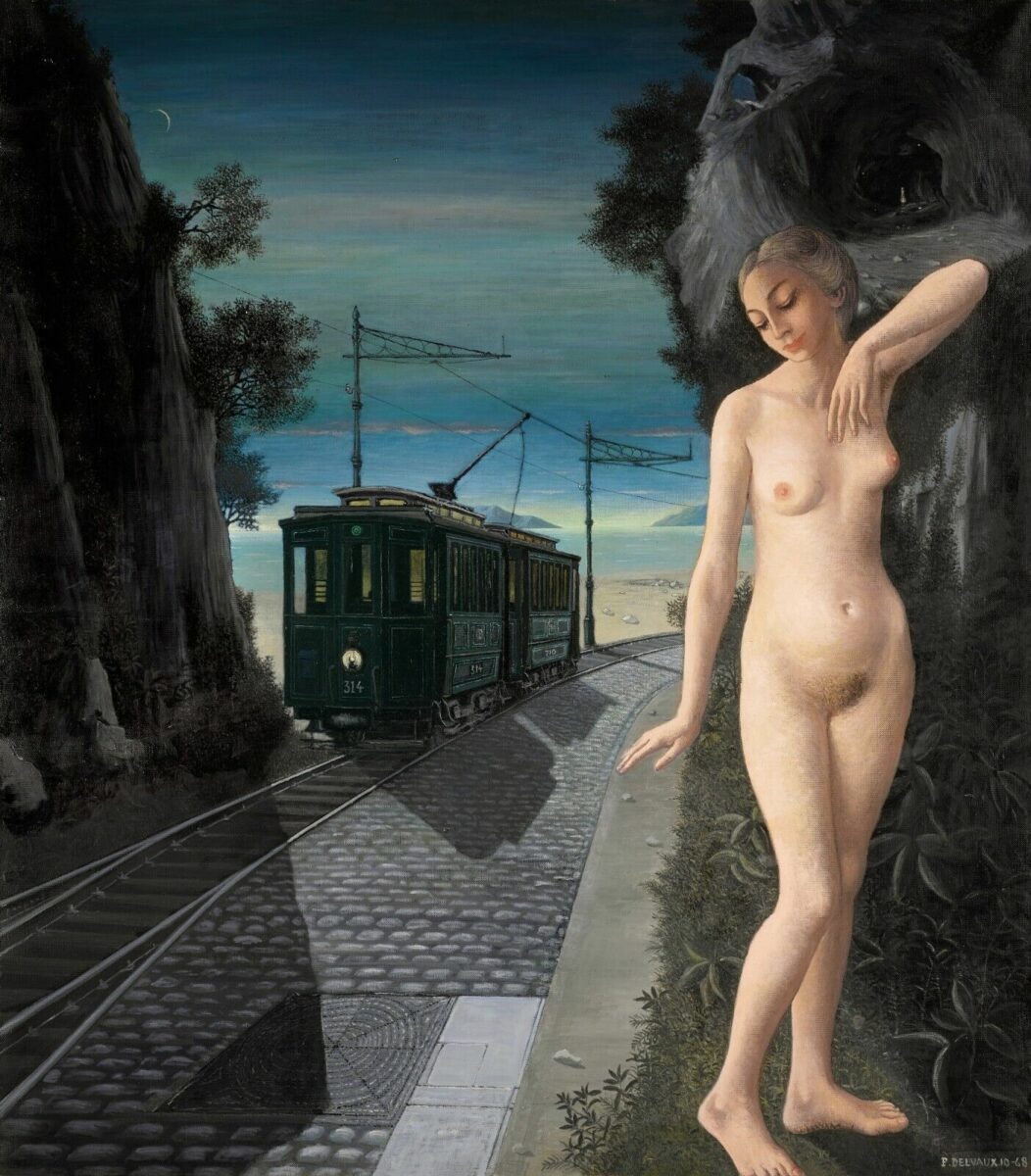

Paul Delvaux: ‘Le Fin de Voyage’ 1968 at Opera Gallery, various locations (top)

2024 marks 30 years since the end of Paul Delvaux’s long life (1897-1994). That fed attractively into the fair design, and the Paul Delvaux Foundation, as ‘guest of honour’, presented iconic paintings, chosen to cover his key subjects. Distanced, expressionless women, trains and skeletons were the leading players in the Belgian artist’s creation of a surreally-tinged world of his own. Many of the 132 galleries also showed him: this high-impact painting gives you two of the big three themes.

It is also the 100 years since André Breton kicked off the surrealist movement, another anniversary widely recognised in presentations. This work originated in 1920, when Man Ray dreamt about a plant growing from the earth, that appeared to be a child’s hand (puériculture is the rearing of children, conceived of as an art or a science). It fits with Breton’s wish to experience ‘a community of perfumes, a summer of desires and dreams’. Man Ray left Paris for Hollywood in 1940: being forced to leave his works behind, he recreated many for American audiences under the title ‘Objects of Affection’.

The surrealists felt an affinity with some ‘naïve’ artists, most obviously Henri Rousseau, but the self-taught French painter André Bauchant (1673-1958) was another. He showed in Paris from the late twenties, having arrived at painting from his pre-war background as a gardener and tree surgeon. Bauchant had a penchant for mythological scenes, but x showed a self-portrait and two of his many wooded scenes with birds appearing to converse with each other.

Here’s some logic to offset all the surrealist escape from it. If you want to make a painting of carpet, why not make it out of carpet? And if you’re better known for fashion than art, why not reference your clothes? Just so, those apparently stray strands of thread reference a signature feature of many of the leading Belgian designer’s wearable productions. The result, perhaps less logically, is appealing on it’s several levels.

Jean Dufy (1888 – 1964), the seventh of 11 children growing up in Le Havre, was also untrained: he worked as a clerk while painting in his spare time, before finding a career in art and design in Paris after World War I. He was clearly influenced by his older brother Raoul (1877-1953), and they collaborated on a monumental mural in 1937. Raoul gave no credit to Jean, who never forgave him, severing contact. If you want a pretty characteristic Dufy, then, there’s a case for choosing the less famous brother, at around 20% of the cost.

Talking of good value for (quite a lot of) money, you can get a prime Hantaï for around £1m. So this was something of a two-for-one bargain: separate works either side of the canvas for the same price. Both are typical of his ‘pliage’ technique: the canvas is first folded, then painted with a brush, and unfolded, leaving apparent blank sections of the canvas interrupted by vibrant splashes of colour.

This struck me as an unusual combination: in fact, according to the gallery, it is a frequent 17th century Flemish trope. Kessel painted the flowers, Janssens the people, in line with the Antwerp duo’s specialisms. As is the norm in the Dutch Golden Age (generally taken to be the century from 1575 or so), one is drawn into exactingly-realised details, such as dewdrops and a spider.

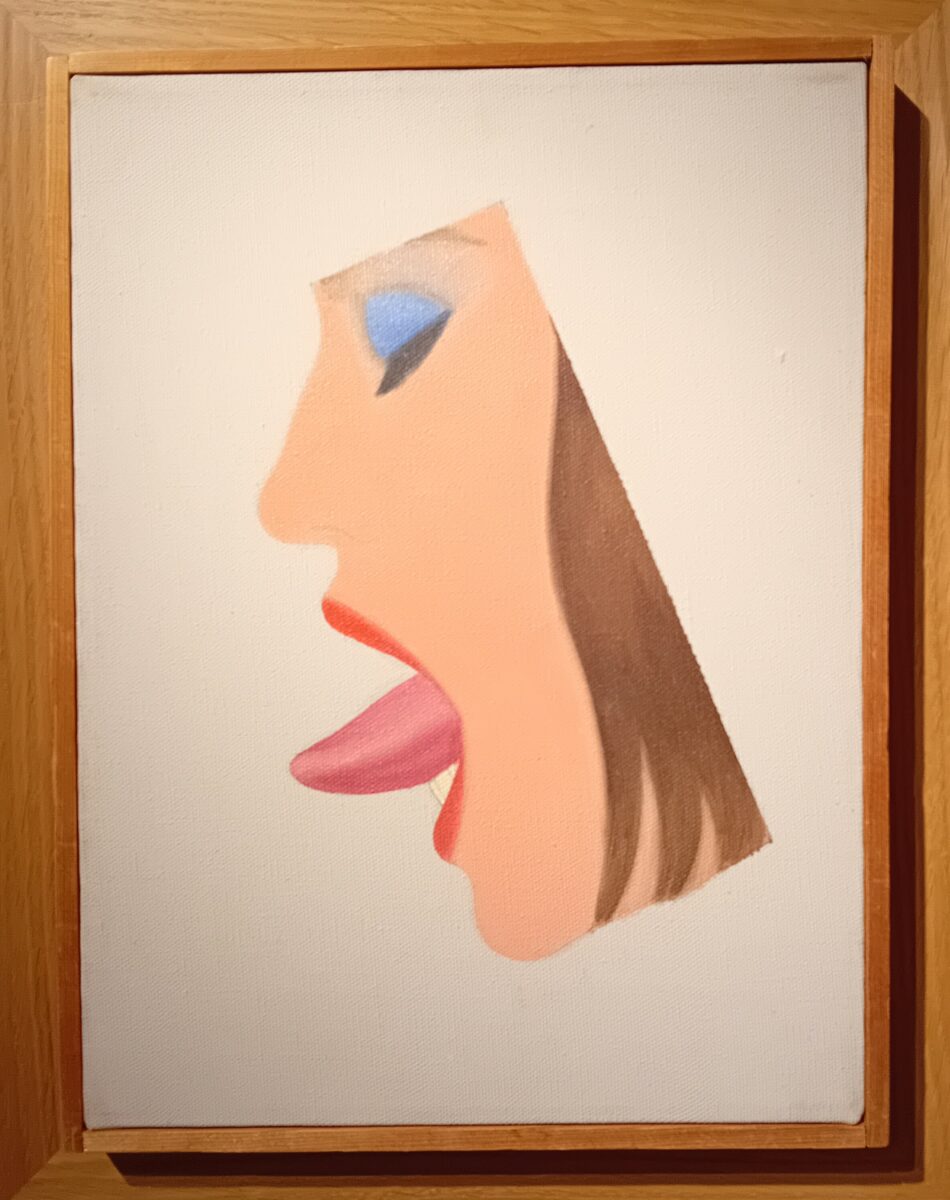

How unusual is this? An impressive solo stand of Wesselmann included this oil study: I struggled to recall seeing another example in which the tongue so dominates the lips, normally his facial focus – then I found a similar work at another stand…

But this is definitely rare: an Antwerp brothel scene from the 16th century – presumably a private commission. The lively figures have a Roman aspect, while the monkey and parrot reinforce the eroticism and air of luxury. The dog may stand in for the artist, as van Cleve (1527-81) often included them in his paintings.

A bird appears here, too, the surprise being the scale of the eagle (and its shadow) once spotted – given how tricky that is! From a cycle of pastel drawings by a Belgian symbolist (1866-1930) who spent most of his career in Paris.

I’m taking a break from ‘Gallery of the Week’ to report on some fairs…

Paul Carey-Kent

Categories

Tags

- André Bauchant

- Bernier / Eliades

- BRAFA

- BRAFA 2024

- Dina Vierny Gallery

- Gallery Berés

- Henry de Groux

- Jan van Kessel II & Hieronymus Janssens

- Jean Dufy

- Man Ray

- Marten van Cleve

- Martin Margiela

- MARUANI MERCIER

- Opera Gallery

- Paul Delvaux

- Samuel Vanhoegaerden Gallery

- Simon Hantaï

- Thomas Deprez Fine Arts

- TOM WESSELMANN

- Willow Gallery