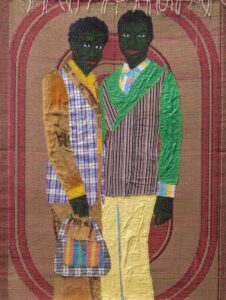

Tate Britain’s new exhibition Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950s – Now presents a carefully curated selection of paintings, sculpture, film, photography, fashion and installation by 46 Caribbean-British artists living in the UK or the Caribbean, which spans a 7-decade period. Art historically the exhibition brings together four waves of artists; artists of the Windrush era; the Caribbean dimension of the 1980s Black Art Movement; artists who came to prominence on either side of the millennium (including artists such as Chris Ofili and Peter Doig, who moved from Britain to the Caribbean); and the nouvelle vague of emerging artists of Caribbean heritage, such as Alberta Whittle, Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Ada M. Patterson.

Life Between Islands is an astounding insight into the rich heritage of African-Caribbean artists, curated by David A Bailey, a curator and member of the Black British Arts Movement, as a celebration of the artistic dialogue between Britain and the Caribbean, forged by the artistic and creative communities that settled in Britain in the 1950s and made a significant cultural impact on the art, music, fashion and film which is embedded in our culture today.

Whilst celebrating the relationship between the Caribbean and Britain from the 1950s to the present day, Life Between Islands also examines some of the more shameful aspects of our history, most notably Colonialism and the slave trade. The exhibition takes a roughly chronological path from the 1950s to now, criss-crossing the Atlantic Ocean as it reconsiders 20th and 21st Century British art history from a Caribbean perspective, in a concerted effort by the Tate and the curator to start redressing the underrepresentation of African-Caribbean artists in Museum collections.

The majority of featured artists are of Caribbean heritage and were either born in the Caribbean and came to Britain as adults or children or were born in Britain. Planning and curation of Life Between Islands began before several years before the recent Windrush scandal and the killing of George Floyd sparked a global wave of Black Lives Matter protests, but these events give the exhibition an additional sense of urgency to look back at some of the woefully racist events of history and our more recent past, and underline the importance of giving a platform to artists of African and Caribbean heritage with which they can visualise their stories and narratives.

Britain’s history is profoundly intertwined with the Caribbean’s. Histories that may be very familiar to Caribbean-British people are insufficiently known in Britain generally. This gap in knowledge continues to have major social consequences for Caribbean-British communities in the UK.

The exhibition is broadly chronological with a series of loosely connected sections examining different themes titled; Arrivals; Pressure; Ghosts of History; Caribbean Regained: Carnival and Creolisation; and Past, Present, Future.

These themes explore complex topics such as the role culture played in decolonisation and the socio-political struggles faced by people of Caribbean-British heritage, and bear witness to the rich and vibrant culture they have created or contributed to. Joyful, large-scale abstract paintings from the 1950s to 1970s by Frank Bowling, Aubrey Williams and Denis Williams can be found in the opening section of the exhibition, titled Arrivals. They were all part of the first wave of artists who arrived in Britain from the Caribbean in the late 1940 and 1950s, with the Windrush Generation of immigrants who the British government encouraged to migrate in order to address post-World War II labour shortages.

This artistic dialogue is a two-way street, for as well as a visual feast of art produced by artists of Caribbean origin living in the UK, the exhibition also features work by some of the most celebrated artists with British origins working in the Caribbean today including Chris Ofili and Peter Doig.

Life Between Islands is the first museum exhibition to look at the relationship between Caribbean and British art from the 1950s to today, and is long overdue. Since we live in an often ‘white-washed’ world where history has often been recorded from a white perspective, this exhibition provides a long overdue platform for post-war and contemporary Caribbean-British artists to tell undocumented narratives and address the racial inequality of our history books and museums shows.

There are many uncomfortable moments in the exhibition, as well as moments of great beauty and revelation, for much of the art on display here tells the painful stories of colonialism, slavery and racism which are shamefully a part of British heritage. However painful it may be to ingest some of the racial injustices of our past, this exhibition is a vital education in inequality, racism and the devastating legacy of the slave trade.

Life Between Islands highlights some important histories from the past seventy years, while some of the art displayed shows that the story goes back much further. The transatlantic slave trade and colonisation of the West Indies formed the foundations for a significant portion of Britain’s global power and wealth, and even Henry Tate, founding benefactor of the Tate, was a sugar refiner. Although, as a wall panel at Tate Britain titled Tate and legacies of Slavery and Colonialism explains, Henry Tate’s business was started in 1859, after the abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire, he still became wealthy by investing in an industry built on profits made through slavery and colonialization.

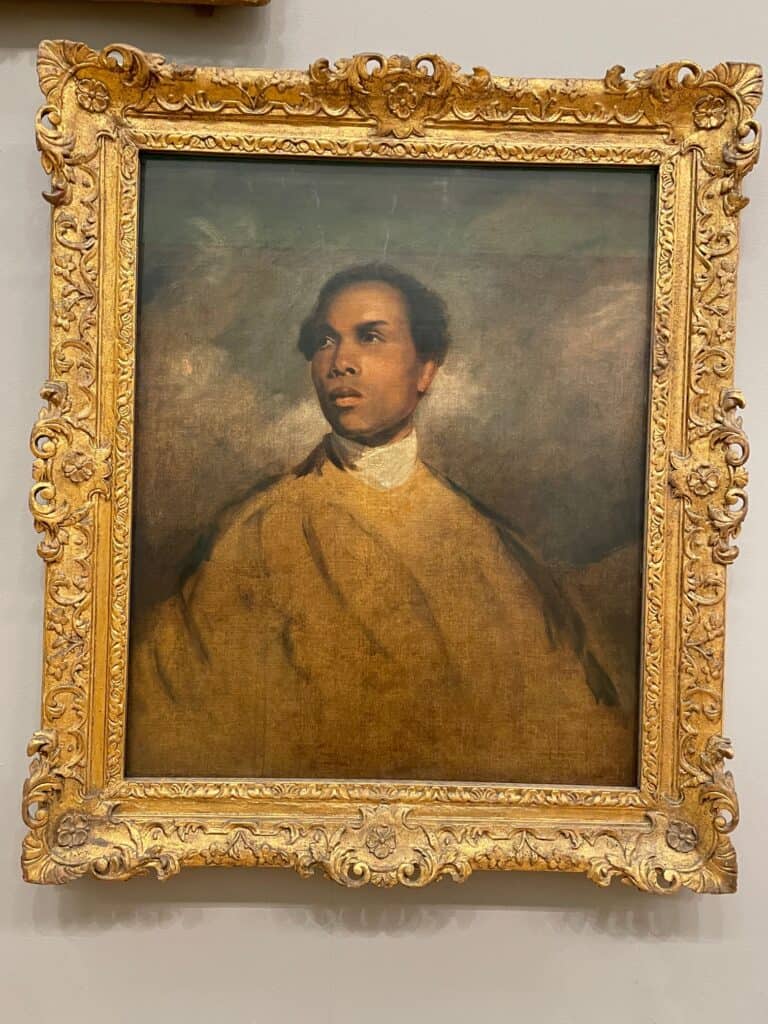

You don’t have to delve deep into Tate Britain’s permanent collection to come across a portrait of an enslaved man painted during colonialism – titled A Young Black Man in the manner of Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) – the painting is exhibited amongst a gallery of white faces from the peak of the British Empire in the 19th Century. The wall panel explains that the portrait is thought to be of Francis Barber, servant of English writer Samuel Johnson, who was born into slavery on a sugarcane plantation in Jamaica and brought to England in 1755 as a slave of Colonel Richard Bathurst, later being made a free man by Barber.

However, with this exhibition and other initiatives such as a Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Network,Tate are making a concerted effort to atone for the sins of our colonialist forefathers, and to redress the racial inequality evident for so many years in museum and gallery shows including their own collections.

It feels timely that this exhibition opened in London just as Prince Charles was in Barbados publicly attending a transition ceremony that formalised the island’s decision to become a republic and remove The Queen as its head of state for the first time since she came to the throne in 1952. The Prince of Wales formally acknowledged “the appalling atrocity of slavery” in the Caribbean, saying “it forever stains our history”.

The very notion that a flesh and blood person could be born or sold as the property of another human being is nauseating to say the least, and the topic of slavery runs a thread from the permanent collection of the Tate to the Caribbean exhibition, which features unsettling but vital works by Donald Locke and Keith Piper that highlight the terrible ‘trade’ of slaves. These works are found in the section titled Ghosts of History, and the artists are associated with the Black Arts Movement of the 1980s and early 1990s, who examined the terrible legacy of colonialism and slavery.

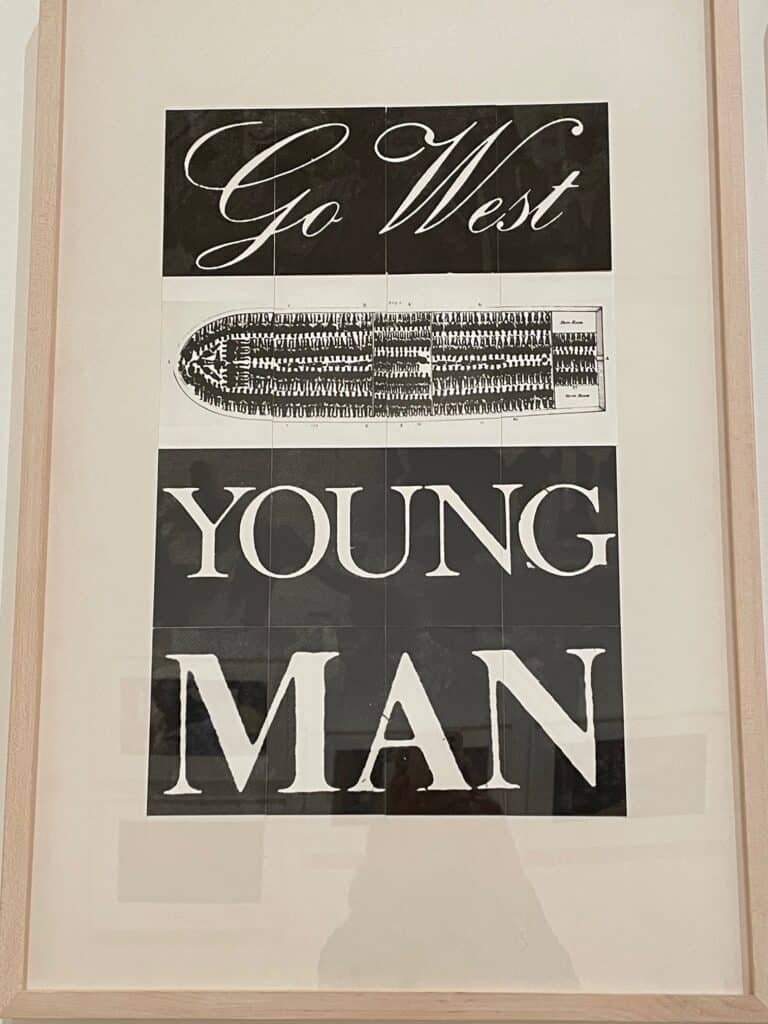

A wall of screen-prints by Keith Piper include one with the words Go West Young Man, and a reproduction of the plan of a slave ship which shows how tightly packed its human cargo were into the hold, lined up in rows with only a coffin-like space for each person.

Piper’s print is titled Trade Winds (1992) and reminds me of a chapter in Reni Eddo-Lodge’s 2017 book Why I’m no longer talking to white people about race. In the book the author explains some shocking statistics regarding slavery, including the shocking figure of roughly 11 million black African people being transported across the Atlantic Ocean to the West Indies, where they worked as slaves on sugar and cotton plantations. An image of a slave ship from abolitionist William Elford’s 1788 book is reproduced in Why I’m no longer talking to white people about race, and depicts the horrific conditions that slaves endured in transit as what was called in the slave trade ‘black cattle’, with bodies lined up one by one, horizontally in four rows in coffin-like conditions which they had to endure during crossings of up to 3 months. Dead or dying slaves were tossed overboard in order to claim insurance money for each corpse.

Artist Donald Locke references slavery in his sculptures: Trophies of Empire (1972-4), a wooden cabinet full of ceramic cylindrical forms that question the human cost of trophies gained through colonialism, whilst the tall spindly forms encased within barriers of Plantation K-40 (1974) refer to the slaves forced to work on plantations whilst shackled with chains, and his abstract minimalist painting Dageraad from the Air (1978-9) is named after a sugar plantation in Guyana, the site of the first rebellion of enslaved people in the country.

I walked through parts of the exhibition with a heavy heart, for many of the featured artists highlight racial injustices from the past, but also those committed in more recent history, showing how racial inequality and racism didn’t end with the abolition of slavery and the fall of the British Empire, but has continued to rear its ugly head.

Photographs by Neil Kenlock and Horace Ové in the Pressure section depict the Black British experience of the 1970s and 1980s, including intimidation by far-right groups, police brutality, the Black Panther movement and the unofficial ‘colour bars’ that restricted access to some public spaces.

A reconstruction of Michael McMillan’s colourful installation The Front Room features a fictional 1970s living room modelled on a typical West Indian home, filled with religious iconography, patterned wallpaper and carpets, a display cabinet and memorabilia from the West Indies.

In an essay for the exhibition catalogue, curator David A. Bailey says of McMillan’s installation: “In this unique study, McMillan explores the position of the home in different migrant groups and examines how these rooms (and specific objects) speak to issues of class, immigration, aspiration, religion, alienation, family and the transition from colonial to post-colonial.”

On the screen of a vintage TV in the room plays a cut-down version of Horace Ové’s film Pressure – the first feature film made by a Black British Director – in the film a young black boy is seen taking part in a job interview where he experiences glaring racial prejudice, and we learn the shocking information that black children were placed in ESN Schools or ‘Educationally Subnormal schools’.

Tam Joseph’s powerful painting The Sky at Night (c.1985) evokes the Tottenham riots of 1985 which were provoked by the death of Cynthia Jarrett while police searched her home, while Denzil Forrester’s unsettling painting Death Walk (1983) portrays the night when his friend Winston Rose was arrested and carried down the street by several policeman – seen in the painting in a crucifix-like pose – resulting in his death in police custody. While a film by Isaac Julien documents the racism experienced by the early founders of Notting Hill Carnival – now a British cultural event to rival Rio’s carnival.

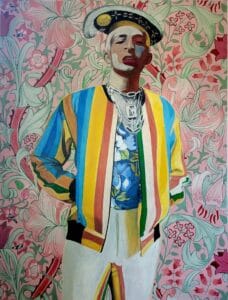

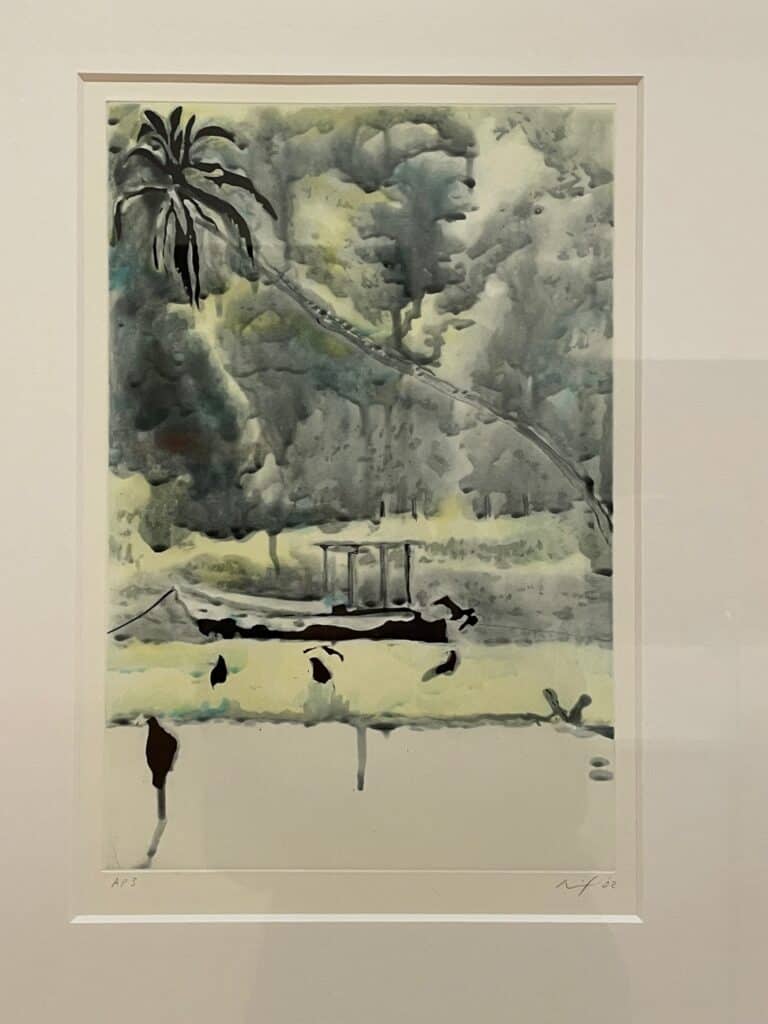

As the exhibition progresses we enter a section titled Carnival and Creolisation, featuring a room of Peter Doig’s beautiful canvases of Caribbean landscapes juxtaposed with antique busts by Hew Locke showing Queen Victoria and other figureheads of the British Empire adorned with feathers, medals and other paraphernalia. The adjoining gallery is filled with two magnificent blue-toned paintings from Chris Ofili’s Blue Rider series, alongside paintings by Lisa Brice of scenes taken from roadside bars in Trinidad’s Port of Spain. Ofili’s Blue Devils (2006) painting is inspired by carnival characters in a Trinidadian village called Pramin, who paint their bodies blue and menace other revellers, while Brice’s paintings Midday Drinking Den, after Embah I and II (2017) and After Ophelia (2018) feature women with blue bodies.

The exhibition culminates with the theme Past, Present and Future and showcases a new generation of British artists of Caribbean heritage, including sculpture and photography by Alberta Whittle, an exquisite 2018 painting Remain, Thriving by Njideka Akunyili Crosby of a young black family in a living room, an installation with Caribbean-inspired costumes and steel drums by fashion designer Grace Wales Bonner, and Blue Curry’s sculpture of a row of seats from a commercial airliner, covered in shells and sand from a Caribbean island, which acts as a reminder of the commodification of the Caribbean and the carbon emissions resulting from tourism.

A hopeful climax to a vital exhibition which will resonate with people of British and Caribbean backgrounds for different reasons, and in the words of Stuart Hall (author of Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands) which are printed in Tate Britain curator Alex Farquharson’s essay for the exhibition’s insightful catalogue: But what this ‘detour through its past’ does is to enable us, through culture, to produce ourselves anew, as new kinds of subjects. It is therefore not a question of what our traditions make of us so much as what we make of our traditions. Paradoxically, our cultural identities, in any finished form, lie ahead of us. We are always in the process of cultural formation. Culture is not a matter of onotology, of being, but of becoming.

Life Between Islands’: Caribbean-British Art 1950s – Now is at Tate Britain until 3rd April 2022:

https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/life-between-islands/exhibition-guide