Lee Krasner has been bowling everyone over at the Barbican. Rightly so, but Tate Britain has just as good a show with a similar template: 50 years of an abstract painting which has tended to be relatively sidelined until recently – due, one suspects, to the sex/race/personal positioning of the artist, rather than the merits of the work. Yet Frank Bowling hasn’t generated the same publicity, though he has arguably been consistently good over a longer period than was Krasner. I reckon he’s developed five substantial modes of work since he found a mature mainly abstract style in the late 60’s, all of them full of colour and tactility, chance and control:

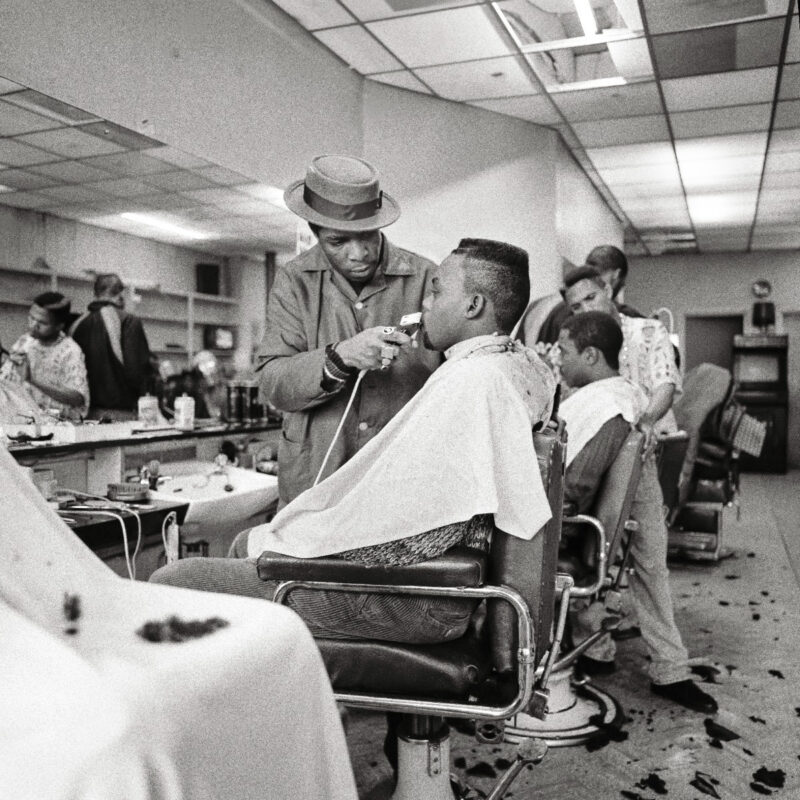

1. The Residual Screenprints in the 1960s – images from his background (his mother’s house in Guyana, ancestral slave history) are almost obliterated to leave a vestigial personal inflection (above is ‘Middle Passage’ 1970).

2. The Map Paintings, 1967-71 – an assertion of the southern hemisphere emerges from seas of colour overlaid with stencilled maps (‘South America Squared’ 1967)

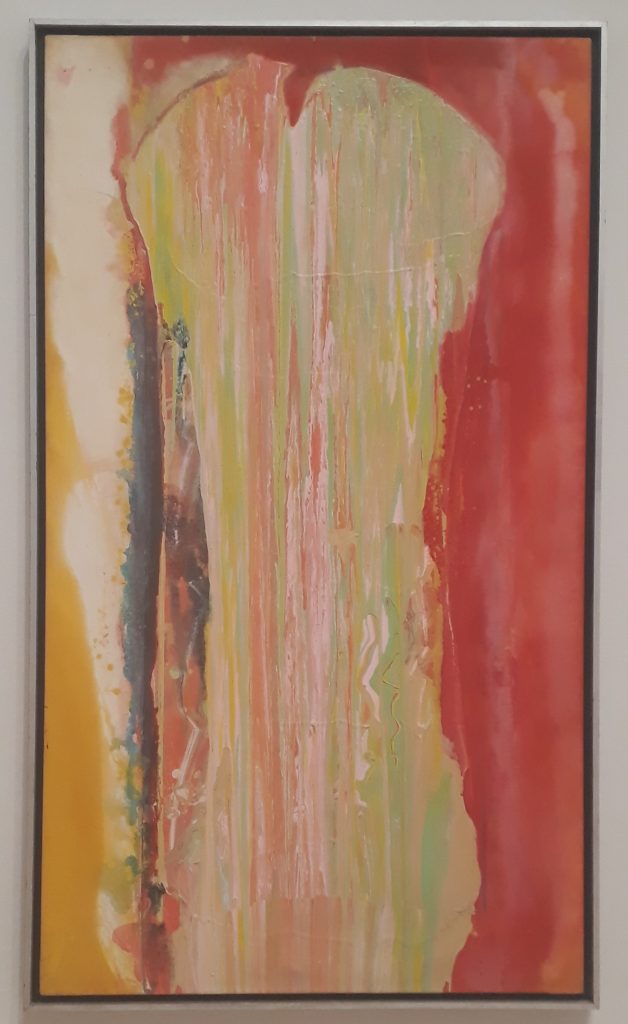

3. The Poured Paintings, 197o’s – layered colours result from employing a ‘tilting platform’ to pour paint from heights of up to two metres (‘Flambourianischoice’ 1983)

4. The Encrusted Grounds and Pools, 1980’s- Acylic gel and foam extends the volume and all manner of objects and pigments are added into a surface which becomes the land it depicts – or, in a variant from the late 80’s, the water on which things float (‘Spread Out Ron Kitaj’ 1983)

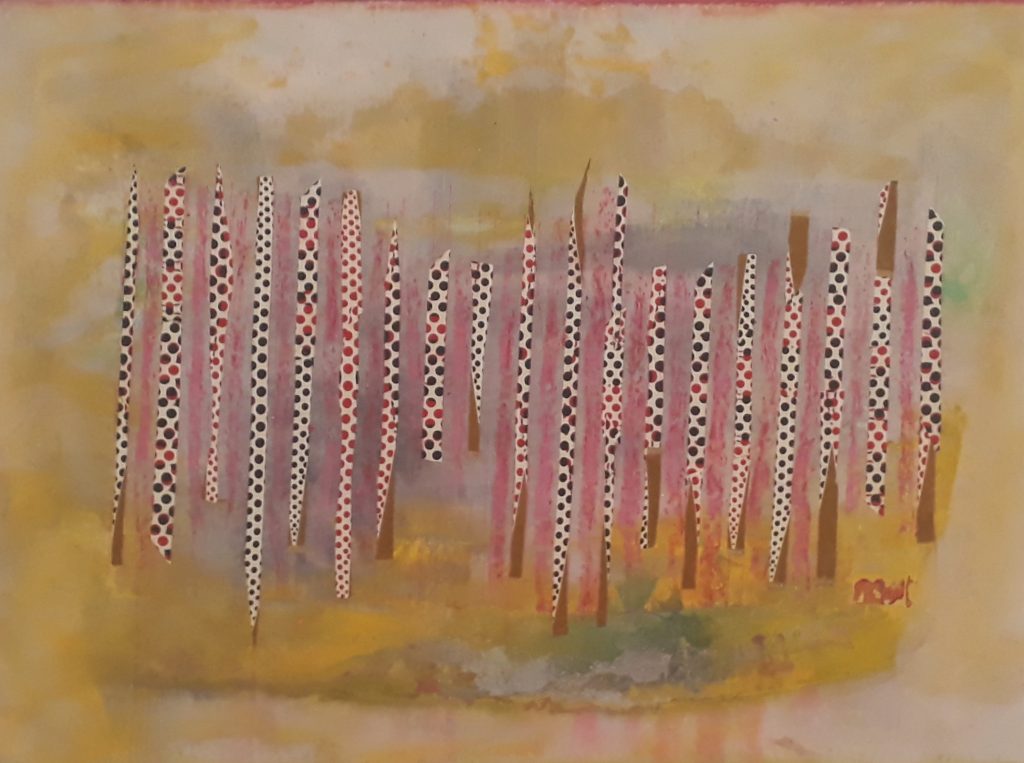

5. The Cut-Ups, 1990’s onwards – collages of cut, stitched and stapled canvases – material yet rickety (‘Jamsahibwall’, 1990).

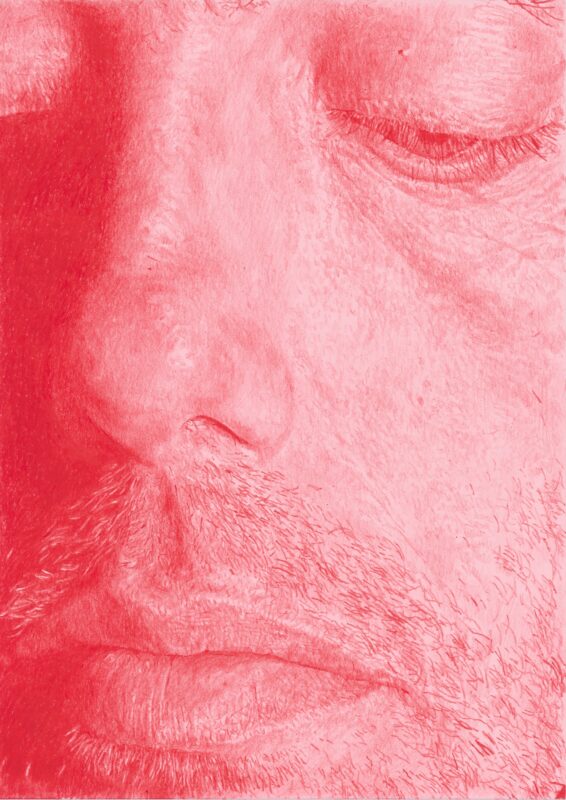

And he’s still going strong at 85: the most recent work in the show (‘Wafting’, from 2018, top of the page) suggests that ‘The Fabric Inserts’ could become a sixth major strand.

Art writer and curator Paul Carey-Kent sees a lot of shows: we asked him to jot down whatever came into his head