Gabriele Neher, University of Nottingham

Old masters rarely come more venerable (and venerated) and instantly recognisable than Leonardo da Vinci. But to think of Leonardo as an Old Master – with all its connotations of being staid, traditional, somehow old-fashioned and boring – is to do this extraordinary man a grave injustice. There is nothing stale or predictable about a man whose personal foibles irritated and frustrated contemporaries as much as his brilliance and creativity dazzled and awed them. One thing is for sure: whatever Leonardo was, old and boring he was not.

May 2 2019 marks the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death in Amboise in France, and this milestone is celebrated in flurry of activity including – in the UK – a brilliant and imaginative series of 12 simultaneous exhibitions around the country, each comprising 12 drawings by Leonardo da Vinci drawn from the Royal Collection at Windsor.

Drawing provides an insight into how this pioneer, who defied all expectations, saw the world around him – so there is no more fitting celebration of his life than putting 144 of Leonardos’s images on display.

It would be fun to engage in a bit of Leonardo exhibition tourism as each of the 12 exhibitions focuses on a specific theme.

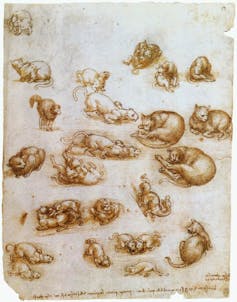

Royal Collection Trust / (c) Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, for example, houses the drawings relating to animals and their movements including the truly beguiling Cats, lions and a dragon (ca 1513-18) which should finally put any suggestions to rest about Leonardo’s status as a staid old master.

Leonardo is watching a cat grooming – but eventually, what he records is no longer a cat but the most enchanting little dragon whose sinous curves mirror those of the cats on the same sheet of paper. Leonardo’s mind never stood still and it is through his drawings that you can see the mind of an artist at work who could paint the majestic Last Supper and derive as much fun from doodling cats.

Workshop apprentice

Leonardo’s beginnings as an artist followed the traditional route of indenture in an established master’s workshop, in this case, the studio of Andrea del Verrochio, a very successful artist in the orbit of the Medici family who was as accomplished a business man as he was an artist.

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

The Renaissance workshop fostered a multitude of talents – at any one time a workshop might be executing bespoke images for a wealthy patron while at the same time collaborating with another workshop on large-scale fresco decorations or structural work or designing and producing ephemeral, gilded papier-mâché decorations for a banquet. Artists were expected to be able to produce exquisite designs for jewellery, clothing and animal livery for the well-heeled merchants of Renaissance Florence. Meanwhile they would also churn out the popular birth trays presented to mothers in celebration of the delivery of a child and panel paintings for a cheaper market, copy heraldic designs and sketch maps.

Renaissance workshops thrived because of the variety of skills brought together under one roof by a master such as Verrochio – the team was stronger than the sum of its individual parts, and it sustained itself through its apprentices. Leonardo though stood out as a master of all trades, as the artist who excelled not at one art but all of them.

Court artist

Leonardo was quite aware of his extraordinary talents and value to patrons and spelled this out in a letter seeking employment at one of Europe’s most lavishly spending Court, that of Ludovico il Moro Sforza, Duke of Milan.

He speaks of expertise in the design and construction of effectively field artillery and bailey bridges; outlines his skills in sapping walls and landscaping; his expertise as an architect and sculptor and also promises that he can do “in painting whatever may be done as well as any other, be he who he may”.

Royal Collection Trust / (c) Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

The Duke of Milan duly appointed Leonardo to his court and it was at Sforza’s court that Leonardo, at the age of almost 30, was to spend the next two decades painting his best-known works (the Mona Lisa, The Last Supper, The Madonna of the Rocks, the enchanting Lady with the Ermine). All the while he was working towards the one commission closest to his patron’s heart – the casting of a life-sized equestrian statue celebrating Sforza’s father.

Leonardo as an artist did not measure himself against his contemporaries alone, but his true competition were the great masters of classical antiquity. And the only way in which he could achieve lasting fame through his work, was to ensure that his works – especially the Sforza monument – became exemplars. These were intended as unsurpassable demonstrations of his skills and knowledge.

The greatest legacy Leonardo left from his Milanese years are his notebooks and drawings (including some of the ones now on show), and one of the reasons behind these drawings was his quest to master everything he might need in order to best execute that monument.

Royal Collection Trust / (c) Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

He needed to understand the anatomy of the animal and its rider – his notebooks show the most extraordinary studies of human and animal anatomy, movement and expression, with Leonardo returning again and again to the same motif, endlessly working on minute variations.

In order to cast the great monument, he would need to understand the behaviour of metals, fire and minerals – as well as the mechanical processes of casting and hoisting the monument. So he studied machines, drew existing ones, improved on old designs and invented new ones. Leonardo wanted to know about the minutiae of textures but also needed to understand a landscape holistically.

Royal Collection Trust / (c) Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

The notebooks are encyclopaedic in their topics, and breathtaking in their intricacy and beauty. It is the ceaselessness of his drawing that provides the key to understanding the timeless appeal of this greatest of artists.

Leonardo died 500 years ago at Amboise, at the Court of Francis I, where he retired after working for some of the greatest patrons of the early 16th century. He travelled with Cesare Borgia’s army and drew some very early bird’s-eye-view maps.

Royal Collection Trust / (c) Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

He stayed at the Papal Court of Leo X (Giovanni de’ Medici) experimenting with mechanical clockwork devices and increasingly focused on his study of meteorological phenomena such as clouds and deluges, yet the one constant was drawing.

So enjoy these drawings that have come down through 500 years of art history and appreciate that you are looking inside the mind of the greatest “Renaissance Man” of them all.![]()

Gabriele Neher, Associate Professor in History of Art, University of Nottingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.