Deconstructing Zaha Hadid’s Art- Forget for a moment Zaha Hadid the architect or designer. All her designs started with a drawing, and especially in the early days, some were worked up into bright, strange visionary canvases. They simply looked unlike anything by anyone else. The current exhibition at the Serpentine’s Sackler Gallery (which her practise ZHA repurposed and extended in 2013) brings together drawings and paintings she made before her first permanent building, a fire station in Germany completed in 1993. The show presents the case that she was a major visual artist in her own right.

‘Metropolis’, 1988; © Zaha Hadid Foundation

The first thing you see hung on entering hits your senses big-time straight away. Metropolis is a red canvas over five metres wide and almost half as high, and seems at first to be clustered objects scattering in flight. Look closer, and it is you, the viewer, who is in flight, over a red terrain marked with roads and green spaces, and fragmenting forms are embedded in it. This work was originally commissioned for an ICA show in 1988. It’s about London, and the dynamic structures are abstractions of urban ‘villages’ erupting with regeneration. What’s going on?

Along with other ‘starchitects’ like Frank Gehry and Rem Koolhaas, she was lumped together by architect-guru Philip Johnson at a 1988 MOMA exhibition under the label ‘deconstructivist’. To understand her as an artist, it’s necessary to deconstruct her work. Mathematics, which she studied in Beirut, runs through all of it. She once described it to me as ‘the mix of logic and abstraction’, which certainly describes her art. When she gave talks about her vision, Hadid liberally scattered extraordinary phrases like ‘multiple morphings and distortions… toptonic topography… fluid organisation… space which becomes pixelated…’. These are ideas she later realised in architecture by harnessing computer power in powerful parametric design tools, but she visualised them before the tools could deliver.

Let’s start with the two most ‘conventional’ or readable projects at the Serpentine, both made when she was studying at the Architectural Association. Meticulously-drawn images from 1977/78 illustrate her idea for a Museum of the Nineteenth Century occupying a string of boxes like train carriages falling from a Thames bridge as if derailed. It’s a comment on history, but it’s whimsical, like the post-modernist architecture surfacing at the time. A very different structure over the Thames is Horizontal Tektonik, made a year earlier. The strange agglomeration of rectangular forms she showed on a bridge is one of Supremacist master Kazimir Malevich’s architektons, quasi-cubist architectural models he made in the 1920s.

Horizontal Tektonik and Museum of the Nineteenth Century, Serpentine Sackler installation view © Zaha Hadid Foundation © Hugo Glendinning

Hadid was pre-occupied with Russian avant-garde artists of the early twentieth century. She played with their works in The Great Utopia project (1992/93) for a Guggenheim New York constructivist exhibition. In an exquisite set of square drawings on show at the Serpentine, Malevich’s seminal paintings, once mounted in a legendary show in Petrograd in 1915, float from the walls as if Hadid were there, but in a dream. Vladimir Tatlin’s vision of a great helical structure over 400m high, the Monument to the Third International (1920), is deconstructed around its spiral frame.

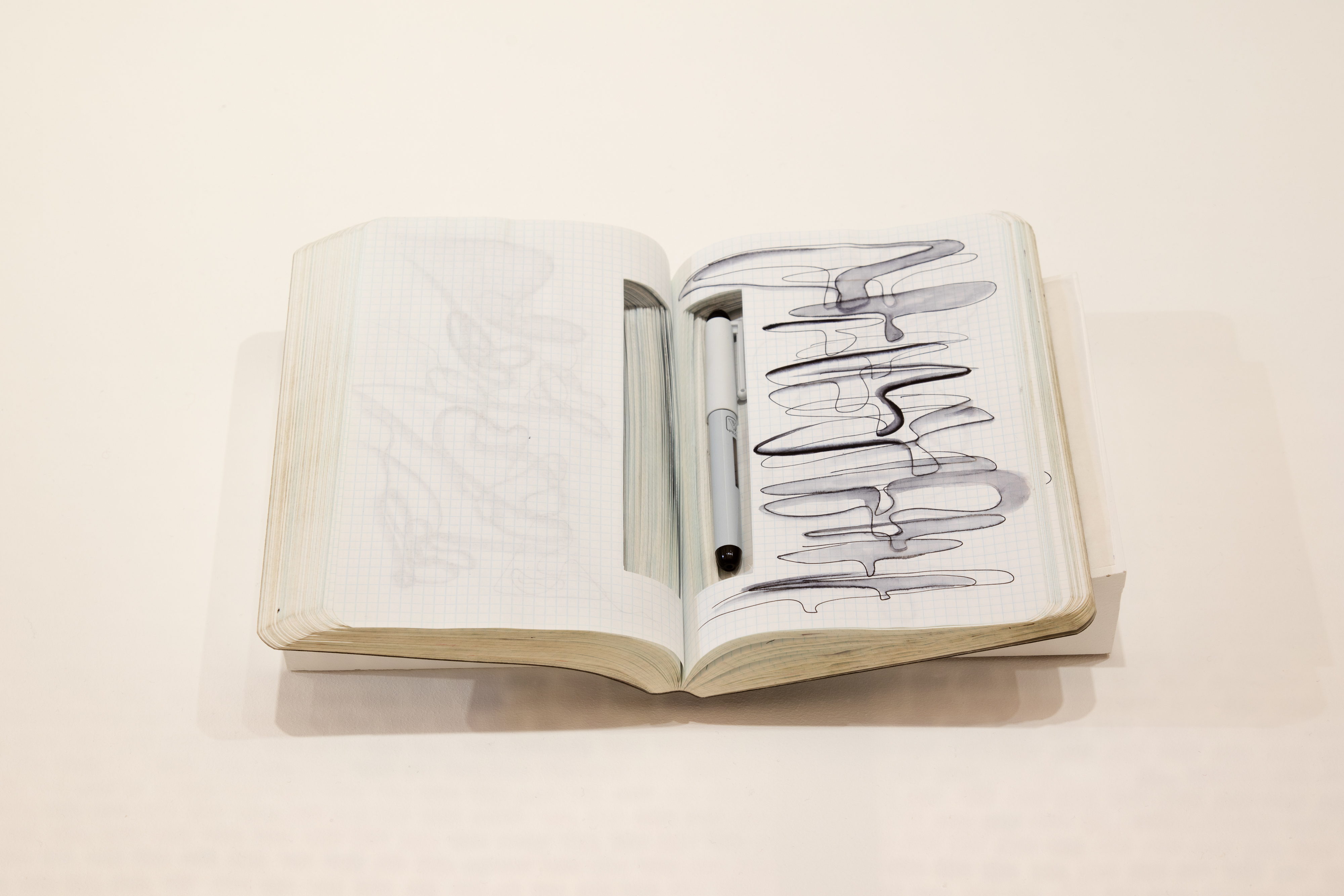

A Zaha Hadid notebook © Zaha Hadid Foundation ©Luke Hayes

These small studies are gems, but the big picture is spelt out in her big pictures. Many works are cityscapes with individual buildings, but Hadid’s were visions interpreting the city rather then objective realisations.

In her Grand Buildings, Trafalgar Square project (1985), London becomes a concave field It’s an early example of how Hadid bent and warped space, not unlike the way Einstein had bent the rigid Cartesian frame of Newtonian space to reveal relativity. Even more warped is The World (89 Degrees) (1983), where the horizon carves right through the city, which is full of modernist visionary structures. Her Museum of the Nineteenth Century and Tektonik mark a river where it reaches the edge of the slice of view that itself is slipped and skewed from the canvas’ edge. Such hallucinogenic distortion of the field of vision is rare in art. It charges the space itself with dynamism.

‘Vision for Madrid’ 1992; © Zaha Hadid Foundation

A precedent for this is the Italian Futurists, who conveyed the sense of movement in new-fangled objects of a century ago – planes, cars etc – by splitting space and multiplying object elements. Hadid’s objects are buildings or blocks rather than vehicles, but they too move, frequently as elements in streams of fragmentation, like those animating Metropolis. Her competition-winning project for The Peak, Hong Kong (1983) produced the canvases Blue Slabs, where below the hill the skyscrapers of Central seem to be rushing into Victoria Harbour, and Confetti: Suprematist Snowstorm, where pixels and slivers populated with detailed three-dimensional shapes are frozen as if in an explosion, like the last frames of Antonioni’s film Zabriskie Point, or Dali’s Exploding Rafaelesque Head.

Confetti ‘The Peak’, Hong Kong 1982_1983; © Zaha Hadid Foundation

The Serpentine show has many more revelations, from the more forensic, analytical explosion of Hadid’s Vision for Madrid (1992) to the deep lugubrious curving shapes in her 1990 works honouring Danish furniture designer Verner Panton, and her imagined subterranean forms for Leicester Square. Also on show are some of her notebooks, with an inner void cut to hold a pen – they remind us that anywhere, anytime, she needed to draw.

Hadid’s ideas about space and form were not just radical, they predicted a unique kinetic virtual reality. Interestingly, the Serpentine offers some animated 3D sequences based on four of the works on show and made by Google Arts and Culture, which run on VR headsets. They’re pretty cool. It’s amazing that it’s taken technology a third of a century to catch up with the visions in Hadid’s head. It was an artist’s head exploding with visions.

ZAHA HADID: EARLY PAINTINGS AND DRAWINGS

Until 12 February 2017 (not 31st December or 1st January) at Serpentine Sackler Gallery, Kensington Gardens W2 2AR