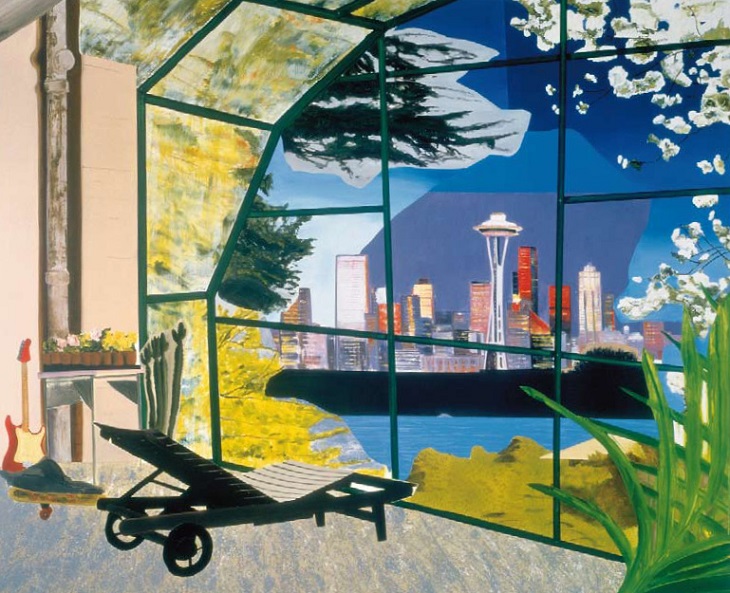

Dexter Dalwood, ‘Kurt Cobain’s Greenhouse’, (2000)

The death of Kurt Cobain was one of the seminal moments of the 90s for all the wrong reasons. It heralded the end of grunge and the start of something new with a harsh lesson about the transience of true genius. The legend lives on, not through sordid tales of heroin addiction or the boy who took a gun to his head, but through some of the greatest music of the decade. Now some previously unseen photographs of Nirvana are about to go on sale, following a trickle of attempts to gain access to the depths of man who already gave us everything.

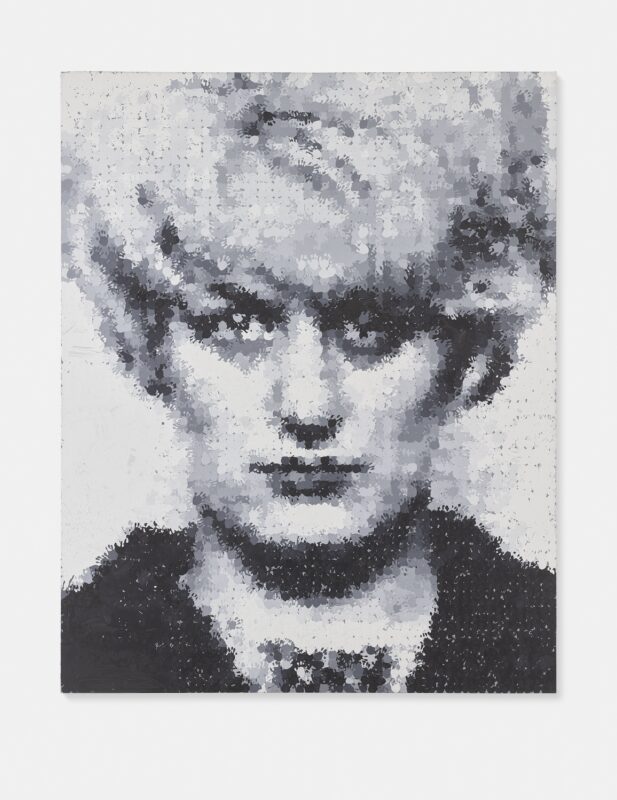

It was never necessary to immortalise Nirvana because the power of ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ is immortal from the gut to the head, but many have attempted to capture the myth. Gus Van Sant’s grim, awkward, inversely sensational Last Days charts the moments of stifled drama before a rock star’s death. Dexter Dalwood crystallised the tension between the myth and the reality in his painting, Kurt Cobain’s Greenhouse (2000), which is a glimpse into our own inability to see the real man behind the façade of fame. A new documentary, Cobain: Montage of Heck, has been timed to coincide with the 21st anniversary of his death, but one suspects that anything we don’t already know will remain hidden forever. Not even his 22 year old daughter, Frances Bean, has much to add.

Earlier this year, Montclair Art Museum staged an exhibition, Come as You Are, exploring the cultural and political scene of the 90s. The show’s curator, Alexandra Schwartz, conducted painstaking, detailed research, concluding ‘It seems to me…the artworld as we know it now, which is so globalised, really came into being during this time. It was a period when contemporary art as we know it now was invented’. She was obviously asleep during the 90s or has never read this column. But the show’s intentions we good insofar as Nirvana typified a mood that infected the whole of US culture, just as Britpop did in the UK, where a new dawn required a new art. This is one aspect of Cobain’s legacy that might just be lacking in intelligent analysis.

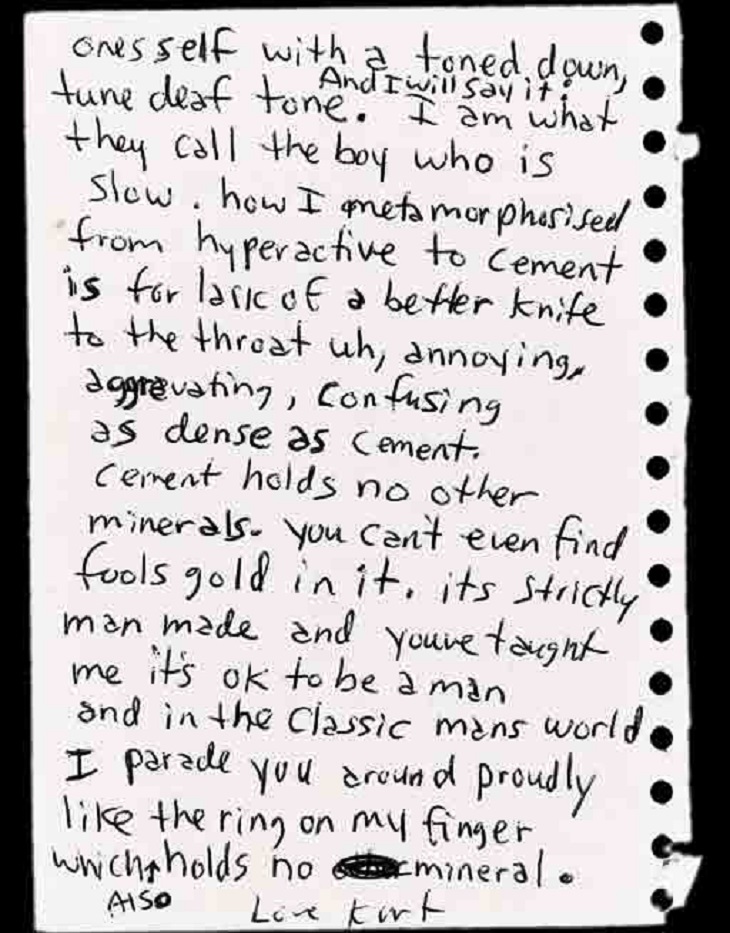

An extract from Kurt Cobain’s Journals

Not so long ago, Cobain’s credit card went up for sale. Someone paid in excess of $7000 for a piece of plastic signed and fingered by the man himself, which eternally represents the unpaid debt that followed him to the grave. And now the former wife of Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic, Shelli Hyrkas, presents On the Road and in the Studio with Nirvana at Glenn Greens Gallery. The exhibition collects her photographs from throughout the band’s career, giving an intimate, although not necessarily rare, glimpse into the daily grind of the voice of a generation. They are selling for between $180 and $780, which is too cheap for the legacy they immortalise and the crass invasion of privacy they represent. It is not at all clear why these pictures are thought to be art, but art loves a rock star as much as anyone else, as Dexter Dalwood will tell you in a few strokes of paint.

Cobain’s journals, however, are a work of art in themselves. They issue from the mind of a man who sought to make everything an expression of both himself and an aesthetic that captured a moment and a profound longing that only art can access. Published in luscious facsimile showing his desperate, scrawling handwriting bubbling with creative energy and ambition on every page, they reveal an astute, thoughtful, sensitive young man who would have otherwise have been lost in the halls of rock legend. The entries recounting his early courtship with Courtney Love, including endless drafts of love letters, are some of the most tender, sincere pieces of literature you’ll ever read.

But if you really want to get at Kurt Cobain, watch Nirvana Unplugged below

Which has every right to be considered one of the seminal musical performances of the century. The band plays a tight, considered set designed to bring the audience close the rupture, always teetering breathlessly on the edge of ecstasy. Cobain is jovial, enigmatic, witty, tranquil but energetic, focused but gregarious, every word he sings pregnant with feeling, and the music flows from him as effortlessly and naturally as the stage lights glint in his golden hair. Listen to the heartbreak in his voice on ‘Where Did You Sleep Last Night’ and you get the same sting of reverence as in the Rothko Room or standing before Tracey’s bed; it’s that same sense of crushing defeat in the face of contingency that only art convey because aesthetics embellishes the worst and renders the rest alluring. It’s one of those moments that makes you weep because you can’t believe that any human being should be capable of such beauty and that something so sublime could be as transcendent as it is transient. The say a picture is worth a thousand words, but with Cobain a song is worth a million cheap photographs that have no artistic merit and show nothing but a bunch of dudes going about their business.

Words: Daniel Barnes