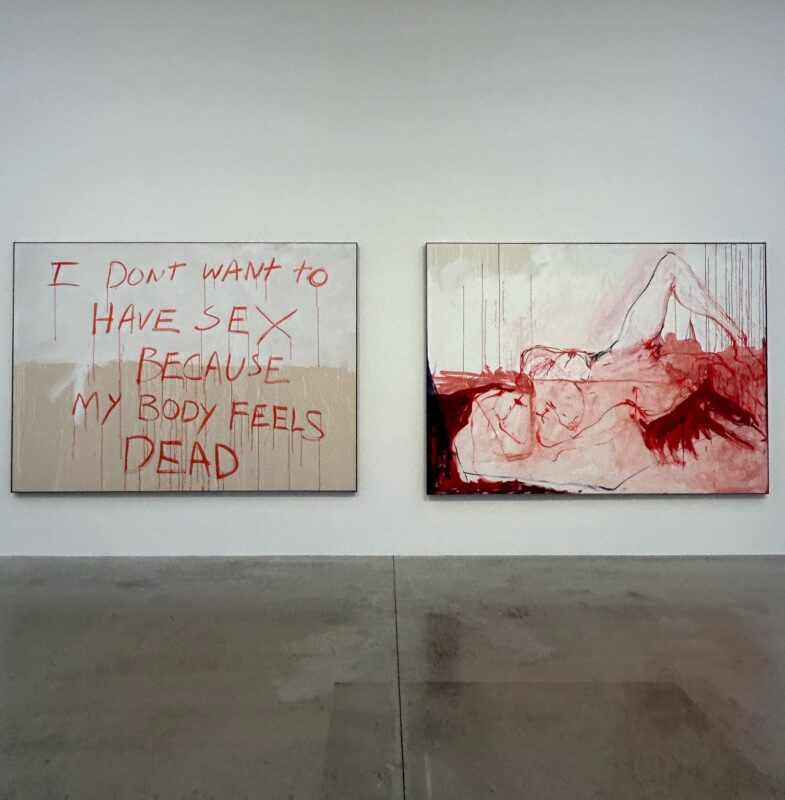

Tracey Emin, Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made (1996)

Auction week heralded the usual suspects: Richter, Hirst, Warhol, Fontanna, Boetti, Klein, Murillo, Twombly, Baselitz, Dubuffet, Basquaiat. Different works, but the same artists endlessly circulating the market. One wonders when all the works by these artists will be exhausted and they are all resold again like some art market version of Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence. Maybe we’ll never know, but we did learn something useful about the price of living artists. It was a good week for modern masters, but something went wrong for the aging YBAs.

A Gauguin painting, Nafea Faa Ipoipo? (When Will You Marry?) (1892), recently sold for £192million, making it the most expensive work of art ever sold. Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for Self-Portrait (1977) sold at Sotheby’s for £14.7million. Over at Christie’s, an early Richter photorealist painting, Vierwaldstätter See (Lake Lucerne) (1969) went for £15,762,500 and Bacon’s Study for a Head (1955), a celebrated portrait of Pope Pius XII, realised £10,050,500.

On one level, the price of art does not make any sense at all: first, the numbers are inhuman, for while £192million is an unimaginable sum of money, twenty, ten or five million is pretty difficult to deal with; and second, it is hard to ignore the notion that the money would be better spent on research into incurable diseases, education or bribing terrorists not to murder civilians. It would make more sense if the money was spent on preventing works of art from being destroyed entirely rather than placing contingently in the ownership of private individuals. But that is the world we live in, so we have to find some comfort in working out how these prices are arrived at.

The Gauguin, a result of a private sale from a Swiss collection, was reportedly bought by the Qatar Museums Authority. It has set the bar, which previously stood at £158million for Cezanne’s The Card Players (also bought by a Qatari), very high indeed, but the way the market is going and the way the Qataris are spending, it does not seem unsurpassable. On the one hand, the price is unfathomable, but on the other hand it is just the top end of prices paid for modern masters like Gauguin, Cezanne, van Gogh and Picasso. Insofar as price is a function of what someone is willing to pay, this is just a reflection of a moment in time.

Bacon, an undisputed master but only dead twenty-two years, consistently achieves prices that fall comfortably within the realm of the unfathomable, topping £42million last February for his Portrait of George Dyer Talking. If we focus on cultural value, determined by art historical importance, as an indicator of the appropriate price for an artwork, Bacon is clearly worth sums comparable to Gauguin.

Aside from the fact that Bacon is widely acknowledged to have been a great artist, always already assured of his place in art history, there is also the fact that Bacon stands out among his contemporaries. While Hockney emerges from British Pop art, defining an individual style under the Californian sun, and lines can be drawn connecting Auerbach, Freud and Kossoff, there is something about Bacon that stands out as unique. He seems to come from nowhere, completely unmatched before or since, as if he transcended art history from the outset. Consequently, his works were and are culturally valuable, which is reflected in current prices; prices we rarely see for his contemporaries. Add to that the dizzying contingency of how much a given individual is willing and able to spend at the time of a given sale, and there is no particular mystery to Bacon’s prices.

Gerhard Richter, Abstrakts Bild (1986)

The real mystery is the high prices paid for living artists. The fact that different works by the same artists keep appearing underlines the fact that artists generally produce more work than you expect. Few are as discerning as Vermeer, limiting themselves to perhaps 36 paintings in a lifetime. For dead artists price is driven by the availability of a finite number of works at a given time, but with living artists in today’s climate the market sometimes has to work hard to convince us that they are not about to produce another one exactly like it. One way it does this is to entrench the work in an immutable art historical context as a golden period of the artist’s work, of which this is an exemplary product. This can be the only explanation for the price of the Richter: in the Richter cannon, it is an art historical relic, a discontinued line of which there are a finite number in existence. We saw this trick with Gilbert & George. Nothing, however, explains the sale at Sotheby’s of Richter’s Abstrakts Bild (1986) for £30.4million. It’s a great painting, a really great painting, but Richter is still making them.

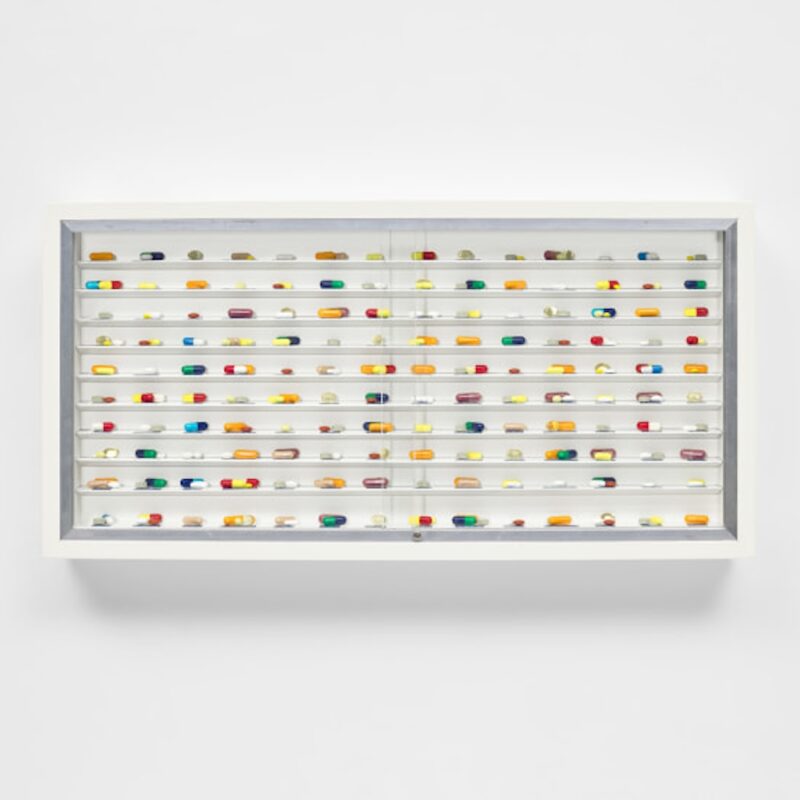

Even armed with this explanation for the prices of modern masters and some living artists, we are at a loss to explain the anomalies in Christie’s evening sale this week. Both Hirst’s Lullaby, Winter (2002) and Emin’s Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made (1996) sold for under the high estimate in a sale where practically everything else was surpassing the high estimate. Art historically, these were key moments in the YBA narrative: the Hirst was the dawn of a new era, and the Emin was the end of obscurity. The Hirst went for £3,050,500 and the Emin for £722,500. The power of the brands and their art historical acumen suggests the price should have been higher.

Despite the fact that £3million is about the going rate for a ‘classic’ Hirst and that – one exceptional Bed and a very desperate Count notwithstanding – this is consistent with Emin’s overall secondary market performance, these works are important enough to have fetched more in a different climate. So what went wrong? They both broke the cardinal rule: if you want prices on the Richter Scale, you have to stop making the work in order to convince everybody of its art historical importance, or at the very least find a way to make it appear scarce.

Hirst may or may not still be making Pill Cabinets (it’s difficult to tell since he lied so often about stopping the Spot series), but nobody really cares that much anymore, which probably means he is making them; otherwise, he has a shed full of them in Devon, if you want one. And Emin recently showed a whole new series of paintings, claiming she had rediscovered and fell in love with the medium all over again. These two major works failed to achieve their highest price because the artists have lost with age a sense of how to immediately situate themselves within history. The problem, as far as the market is concerned, is that the YBAs are still recent, if not all-too-living history, and for the most part that history keeps repeating itself.

Words: Daniel Barnes