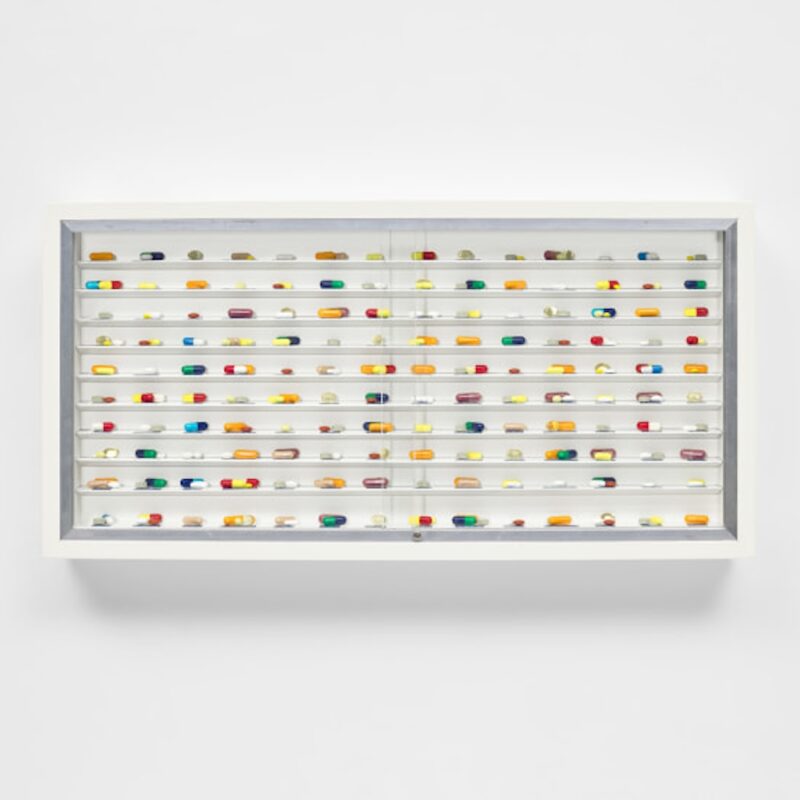

Damien Hirst, Lullaby, Winter (2002). Photo: Prudence Cumming Ltd/Damien Hirst and Science

Damien Hirst sold a lot of very expensive art between 2007 and 2008. So much that he became the world’s most expensive living artist, which gave him the power to do whatever he liked. Next week, the seminal Pill Cabinet Lullaby, Winter is going under the hammer at Christie’s, but it has a curious history as an unfulfilled promise that had momentous effects.

In 2007, Hirst’s Beyond Belief exhibition reportedly made £130million, while he netted a further £50million from the sale, to a consortium that included himself and his dealer Jay Jopling, of the infamous diamond skull, For the Love of God. That same year, he superseded Jasper Johns’ record for the most expensive work by a living artist sold at auction with Lullaby, Spring for £9.65million. Then in 2008 he bypassed his galleries to sell £111million worth of new work at Sotheby’s in the sale he called Beautiful Inside My Head Forever, on the very night Lehman Brothers collapsed. While Hirst remains Britain’s most expensive living artist, a title that Peter Doig twice threatened to take last July, he has been knocked off the world top spot by Jeff Koons whose Balloon Dog (Orange) sold for $58.4million at Christie’s New York in 2013.

Hirst is a natural entrepreneur and has always surrounded himself with people, like his celebrated business manager Frank Dunphy, who realise the optimum potential of the brand. He negotiates 75% from his gallerists, manages private sales of new works and holds on to or buys back old works, so he can control his prices. Some people think this is instead of his lack of artistic talent, but those people are blind, joyless philistines who pathologically despise talent and success in others. If you have ever gazed long into the watery eyes of that sheep trapped in its tank of formaldehyde, you will have seen those sullen eyes, pregnant with longing, gaze back you and say ‘it’s almost all right’. That simple but powerful experience is the mark of a great artist. Somebody with this much business sense and artistic talent is bound do well, so what he did after becoming the most expensive living artist is nothing short of ludicrous. Genius, but ludicrous.

The diamond skull and the Sotheby’s sale drew a line in the sand as the most audacious, impertinent and outrageous thing he could do. Hirst could do just about anything, and get away with it. So he retired to his garden shed in Devon to confront his final demon –that awkward craft which thwarted him so profoundly that he came up with the idea of the Spot Paintings. After many months in hiding, he emerged with a series of paintings that he had painted himself, with his own hands, without any assistants.

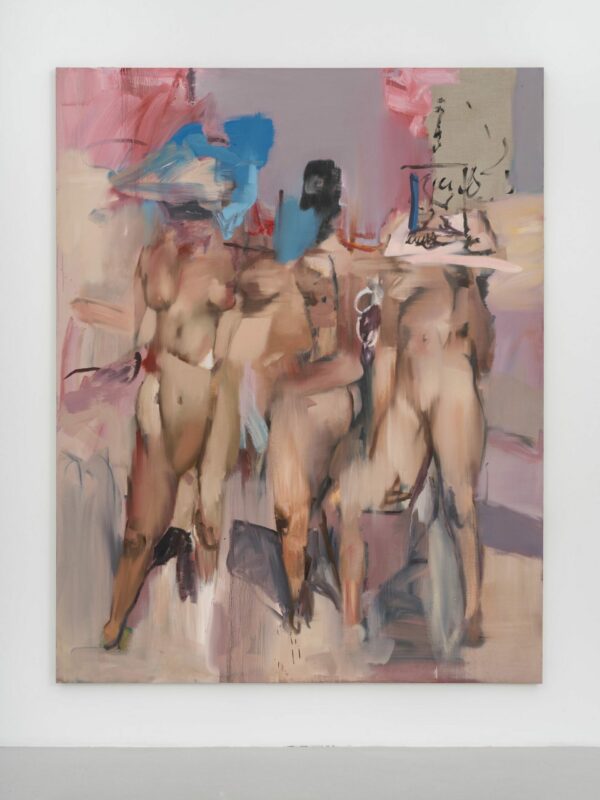

Damien Hirst, The Meek Shall Inherit (2009). Photo: Prudance Cumming Ltd/Damien Hirst and Science

The fruits of these labours were shown at the Wallace Collection in 2009, in No Love Lost: dark, mucky swaths of Prussian Blue, somewhere between still life and Damien’s greatest hits, depicting skulls, cigarettes, roses, lemons, iguanas and shark’s jaws. Although almost universally panned by critics as proof that Hirst is a talentless charlatan, this move incomprehensibly enforced the Hirst myth. These paintings were so strange and so incompetent it was unbelievable that the man who made A Thousand Years could have had anything to do with them, but the fact that he had the courage and the audacity to do it only cemented his position as the untouchable king of the artworld. Hirst had transcended his own myth by showing terrible paintings at the Wallace Collection and selling them at a premium as the only artworks he’d ever produced himself. There were two other exhibitions of paintings, Nothing Matters (2010) and Two Weeks One Summer (2012), the latter of which inspired Jonathan Jones to compare Hirst to Saif Gaddafi, which only proved that even if Hirst was a delusional despot, he had the courage of a centurion and the impunity of a saint.

So long as he is Britain’s most expensive living artist, Hirst can afford to explore with gleeful abandon whatever misadventure takes his fancy because every time a classic Natural History work or a Spot Painting is on the block, the price it achieves guarantees the value of another bizarre painting. This market confidence, bolstered by a gentle shift in artistic direction, accounts for the success of his latest Black Scalpel Cityscapes series, which has met with the warmest critical reception of anything he has done for years. People like these works because they are all Hirsty in their shininess and demure brutality, but they are also pictures of things, and people like pictures of things more than anything else in the world. But people also feel sure that Britain’s most expensive living artist can do no wrong.

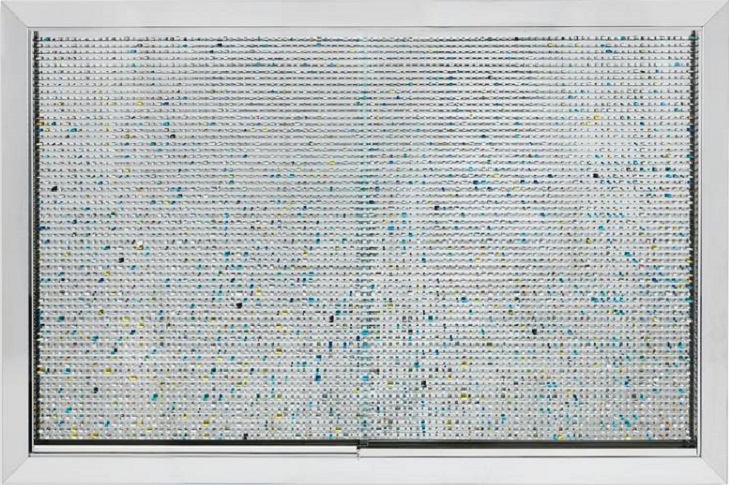

There is, however, a strange glitch here, which explains how the skull, Sotheby’s and the paintings happened as the aftershocks of a vote of market confidence. In May 2007, Christie’s New York sold Lullaby, Winter for $7.4million to an unnamed Asian buyer. So when Lullaby, Spring – the second in a seminal quartet of Pill Cabinets – came up for sale in London just five weeks later, its record-setting price was due in no small part to the hubris generated by the first cabinet, for high prices only beget higher prices. Lullaby, Winter is artistically important in Hirst’s practice, but it was also the catalyst that finally drove his market into the stratosphere. The idea that it has been languishing in some important collection and has been lent out to major retrospectives in London and Doha only gives it kudos in next week’s sale. But the work was never paid for and to this day remains the property of Christie’s.

The very event that propelled Hirst was itself an unfulfilled promise. This mean that Hirst’s meteoric mid-career renaissance as a millionaire and a painter was predicated on an error: although the cabinet realised that price in theory, which begot the price of the next one and so on, no money ever exchanged hands. In monetary terms, Lullaby, Winter, has a null value – it is just a void in Christie’s accounts that created an explosion in Hirst’s accounts. We need to talk about Damien because a man who doesn’t even need his creditors to keep a promise and still succeed is a man whose powers truly do transcend all that is rational and logical. We also need to talk about Damien because none of this really matters when you look upon those 9000 pills with the wistful hope of salvation and only see in the pristine surface of the cabinet the reflection of your mortal face, forever decaying as the rich get richer and the poor get poorer.

Words: Daniel Barnes