Cato Ouyang works in a subtle terrain where power becomes normalized and meaning is shaped through systems that present themselves as benign, necessary, or even protective. Rather than positioning authority as an external imposition, Ouyang examines how it is absorbed into daily life, circulating through objects, spatial protocols, and inherited cultural forms that quietly discipline bodies and define limits. These forces are not abstract but corporeal, shaping how vulnerability, endurance, and selfhood are lived over time.

Ouyang’s practice spans sculpture, installation, moving image, performance, and, more recently, painting. Each medium is approached as a contingent mode of inquiry rather than a fixed identity. Forms are selected for their capacity to register specific conditions such as duration, weight, tactility, proximity, or distance. This interdisciplinary approach allows ideas to migrate between registers. Physical sensation in one work may reappear as psychological pressure or conceptual tension in another. No single medium is privileged. Instead, the work unfolds through dialogue, friction, and occasional dissonance across forms.

Material decisions are similarly attuned to layered meanings. Hand-carved wood and stone, cast elements, organic matter, appropriated texts, and historically resonant objects are brought together through processes that feel both deliberate and provisional. These materials carry personal, cultural, and historical charge, yet Ouyang resists symbolic closure. Knowledge is embedded through making, through touch, repetition, and transformation, so that meaning accumulates gradually rather than declaring itself outright.

Across this varied output, Ouyang consistently returns to structures associated with care, preservation, and regulation. Forms suggest enclosure, shelter, or support, while simultaneously revealing how such gestures can become mechanisms of control or partition. The body emerges as a contested terrain that is protected, surveilled, and divided. Distinctions between safety and constraint remain deliberately unstable. This ambiguity is central to the work and allows tenderness and discipline, repair and harm, to coexist without resolution.

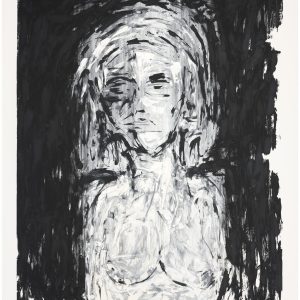

Figures of monstrosity, animality, and toxicity surface not as spectacle but as coded references to psychic and social estrangement. These motifs function as indirect languages for articulating alienation, particularly as it is experienced by subjects positioned at the margins of dominant historical narratives. By abstracting and fragmenting the body, Ouyang proposes alternative ways of understanding representation and self-definition. These approaches resist coherence in favor of multiplicity and refusal.

Viewers are implicated through their own physical and perceptual negotiations of space, scale, and attention. References drawn from personal memory, institutional systems, and collective history remain open-ended. The work encourages sustained engagement rather than interpretive certainty. Meaning emerges through duration and proximity and asks viewers to notice how their own bodies are oriented, restrained, or invited within the work.

Grounded in embodiment and persistence, Ouyang’s practice approaches care as a complex and compromised condition rather than a stable promise. Intimacy and harm are acknowledged without dramatization. The work’s quiet intensity lies in its insistence on staying with unresolved tensions. Through material encounter, spatial awareness, and time, Ouyang invites a reconsideration of how power is internalized and how alternative forms of being might be imagined within or alongside it.

Cato Ouyang earned their MFA from Yale University and has exhibited at Night Gallery and François Ghebaly in Los Angeles, as well as SculptureCenter and Lyles & King in New York. Their work has been included in international exhibitions across Europe and Asia and is held in permanent collections including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Nasher Sculpture Center, High Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum, and Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Ouyang is represented by Lyles & King and Night Gallery and lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

Phillip Edward Spradley: There is a consistency to your palette, earthy and muted tones that feel grounded rather than decorative. Which makes me wonder how do you approach color in your work? Does it emerge primarily from material choices, from context, or from the emotional register you want the work to hold?

Cato Ouyang: If I get carried away thinking about the cultural, spiritual, and political uses of color, my worries become prohibitive. In my MFA program, there was a faction of sculptors who thought that all color in sculpture should be inherent. They scorned, as somehow idiotic, the act of using paint to change the color of an object. I was twenty four then and took this discourse to heart; less so now, but color remains an ongoing negotiation.

The earthy hues that emerge in my work are of a patina that develops on the materials and objects as they get dragged through the street or around the floor of my studio. Part of my process involves making or finding parts individually, and then storing them in piles. Things get dirty, sometimes they break. My issues with control and fear tend to block me from working. So I set up conditions for certain decisions to be made for me, enacted by the world, and then return to deal with the changed object.

Another part of my palette consists of pastel, babyish colors: pinks, pale blues, sage greens. Sometimes I trace this back to the first time I dressed a sculpted figure in a child’s pink fleece; that was in 2020. But if I look back on work from before that, this pastel color scheme was already present. It is possible that those colors are connected to my childhood memories of tract houses and strip malls. They were chalky, washed out spaces. Maybe I am trying to work from a place that dignifies nostalgia. Nadia Seremetakis puts it beautifully: “In English, the word nostalgia implies a trivializing romantic sentimentality. In Greek…nostalghiá is the desire and or longing with burning pain to journey.” For me, it may not be about the uncomplicated desire to go back, but rather the pained longing to journey despite a fear of going back. I have spoken in the past of how I found childhood horrifying. It is not that I never felt happiness then, or love or safety. But I was powerless. My fixation, my cyclic return to memories of that period, is morbid.

In your sculptural and installation works, there is a delicate sense of precariousness in the way multiple objects are physically balanced. Although the works involve many materials and forms, they often feel as though the elements could not exist without one another. How do you think about the relationships between tension and restraint

I am–or at least I consistently claim to be–interested in transformation, mutability, and morally ambiguous spaces. So how do I make the work do that? Some of my early work, as much as I stand by it on its own terms, was not doing it, it was representing it. I worked with myths and symbols because I tended toward metaphor, where an image was meant to stand in for an idea.

I thought, how can the work be born of the forces of indeterminacy and liminality, versus coming from the other end and picking references to illustrate them? To me it involved introducing more unknowing into the process. So rather than, say, creating a reliquary that visually referenced Janus as a symbol of the liminal, I allowed for conditions in the studio in which objects encounter, embrace, smother, penetrate each other. Then I learn from those encounters.

A few years ago my work involved references to chaotic systems, which give us the notion of the “butterfly effect.” In my sculptures, the balancing and tenuous connections are an honest record of how one thing is contingent on another. The long process of their negotiation lives exposed in the sculpture, with all the mistakes and erasures and retrials marked in the work. The sculpture, in its precariousness, may project a perceived lack of strength, but in fact it is undergirded by ingenuity of engineering. Nimbleness lasts, softness lasts. I watched a film the other night, Wild Reeds by André Téchiné. In one scene, a substitute teacher has his high school students analyze Aesop’s fable of the oak tree and the reed. The teacher admonishes a young fascist for being rigid like the arrogant tree, which is ultimately felled by the wind, while the pliant reed persists.

I appreciate your reflection on chaotic systems and on the reed’s capacity to endure through flexibility, which frames precarity as a form of strength rather than weakness. How does this understanding of resilience and contingency carry over into the way you think about the body in your work, even when it is not explicitly represented?

A body is a fraught site; at the same time that it connects a person’s consciousness to the miracle of the world, it is sexed, raced, exploited and assaulted, subjected to self harm and disordered eating, hated for its natural shapes and textures, manipulated into performing unnatural feats. For much of my life I despised the feeling of being in my body, I wanted to negate its physicality. I had an IUD for eleven years, and even though it gave me infections for half of that time, removal was unthinkable because the device negated the aspects of my feminine physicality that I despised more than I despised being sick.

My compulsion is to master the feeble machine of my body and make it tireless, virtuosic, beautiful. Artists, athletes, and laborers work until we ruin our joints, tendons, respiratory systems. I always romanticized that and insisted on enacting it even while hearing from the brokers of “self care” that I should not–until I reached a point I could not continue to enact it. That was a few years ago. Still, an inner conflict persists in which I am at odds with what I want from my body and what I am told I should want for my body. I embrace and center the spirit of this conflict in my work.

I refer occasionally to a text by Maxine Sheets-Johnstone titled The Corporeal Turn. Her work centers on something she terms the tactile-kinesthetic body. She puts it like this: on the surface of a body, contact creates pressure, and pressure creates deformations. It is through deformations of the flesh that a creature recognizes what it touches. In being deformed, we give in to the world; in giving in, we understand what we encounter.

Failure and weakness are a kind of deformity, which at a visceral (not intellectual or philosophical) level I find repugnant. Yet it is through being deformed that we fathom the world. Fathom derives from the root word faden, which refers to the six foot span of outstretched arms. To fathom something is to literally embrace it. I was very moved by this when I learned it. That is my hope for the elements of my work, be they objects, images, or moving images: that they deform, fathom, embrace, give in to each other.

You have used display structures such as pedestals, cases, and enclosures that subtly guide how viewers look and move. What draws you to these formats, and what assumptions about value, protection, or authority are you interested in activating or unsettling through them? Do you see a hierarchy in these structures?

There was a period of time in which, on principle, I rejected rectilinear tools of display. I saw the rectangle as evil, Modernist, and masculine, and the museum as a violent site of plunder and false site of learning. I also bristled at the idea of raising a work off of the floor for ease of viewing what then felt less like art and more like merchandise. No, I thought, you’d better bend over and get on your hands and knees to look! There was something to coercing the viewer’s body to fold or stretch into postures similar to those of the figures embedded in the work. That visual echo felt poetic and vindicating.

At a certain point, I tired of contorting myself in ways that felt increasingly untenable in order to avoid Eurocentric, Modernist references and tools. Reflecting upon the structures, influences, and conventions that we inherit, I wanted to contend with this inheritance rather than negate it. Around 2019, I started altering and building furniture from domestic and scholastic spaces; that may have been the thing that reintroduced the rectangle to my work. The chair or table is a charged site of gathering, work, and discipline; so the platform, in the form of furniture, was not asserted as a neutral surface, but as something layered with power and sociality. The pallet, display case, and apple box are all objects that reflect how our environment is engineered. In the context of anthropology, “scaffold” refers to frameworks like language, institutions, and shared beliefs that guide behavior and facilitate learning within a culture. That may be key to how I engage display structures.

Can you talk about your relationship to language and writing in your practice, and what working with text has enabled for you in ways that image, object, or gesture alone could not?

My magnum opus from 2020 basically asserted the ultimate failure of language to relay meaning or enact justice, so when I evoke text, it is often from an unraveled place. It has been some time since text appeared in my work, as my process of making sculptures and paintings has been largely nonverbal for the last couple of years. Previous work incorporated mostly appropriated texts: from Jean Rhys, Clarice Lispector, Ovid, Ezra Pound, Calvino, Anne Carson. Poetry and literature help me live life–that is, they save me–which on a fundamental level allows me to make art. I write very sporadically, without any discipline. I feel I need an audience for it. Sometimes I go half a year between periods of writing. Sometimes I sit down and write in response to my finished sculptures and paintings, a kind of private ekphrasis, and those texts end up being quite rhapsodic. But for the time being, their home is unknown.

Parts of the voiceover and subtitles in the films I made in 2022 were appropriated from various texts including The Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston, Eros the Bittersweet by Anne Carson, A Lover’s Discourse by Roland Barthes, and medieval literature about mandrakes, among other sources. The choice of books was largely what I happened to be reading while making and editing the film. I remember Roe v. Wade was overturned that year, and this guided some of my reading. Those passages were woven in with journal entries and letters that I had written to friends. That was a collage process as well; the text was not scripted specifically for any of the moving image, but rather paired together in editing. My intention in that was to invite a perceptual stutter in between the two things, the thing that you’re seeing versus the thing that you’re hearing, and see what is active in that negative space.

Collaboration plays an important role in your performance and film work. How does working with others shape the direction of these projects, and how do trust, care, and authorship factor into these exchanges for you?

While it is rewarding, team work is arduous. I have witnessed artists and filmmakers who, with the charisma of a cult leader, are able to coax out incredible things from their performers or interlocutors in a way that does not feel cruel. Whatever that is, I don’t have it, or at least I have not yet earned it. I am not good at putting people at ease or encouraging them. I cannot even encourage myself.

I do not like being perceived while I’m thinking. So, when the camera is rolling, people are being paid by the hour, and I’m having to make decisions on the fly…I am in a state of high agitation. My inner monologue when I’m working alone consists largely of scathing self reproach, and that is basically how I keep myself accountable and focused; so that of course doesn’t translate into directing other people.

I can be paranoid about whether a collaborator is tired or hungry or uneasy. So, knowing that I can be tentative about pushing another person to a point of productive discomfort, my approach is to orchestrate conditions that allow the thing I’m looking for to emerge without me drilling it out of someone. Literature and writing, per your previous question, were tools I used with the dancers who worked on THREE BETRAYALS and one of the musicians I worked with on Syzygy. As a way of structuring our time together I would send them excerpts from these books I was reading, and we would do free writes together, exchange them, and respond to each other’s writing. During part of our rehearsals I would read these freewrites aloud as they ran through different improvisations. As I read aloud, I observed them, and from that, the movement and sound sequences in the final work took shape.

Are there questions, materials, or ways of working you are currently circling that feel unresolved or newly opening up for you?

This month, in residency at the Hermitage Retreat in Manasota Key, my bedroom opens onto the sand about a hundred feet from the sea. I came with a suitcase of materials to make large cyanotypes, because here I have the Florida sun and a slop sink, both which do not exist back home.

I try not to be too knowledgeable about technique, but what I have chosen to know is that a cyanotype, while technically a photographic process, was originally developed as a way to make copies of notes and diagrams. An architectural blueprint is a form of cyanotype. So the process is a kind of language for transmitting and reproducing information. I spend my days building different sculptural assemblages and photo collages on top of the coated substrate and thinking about what kind of information I am trying to transmit, while the sun does its work. It is a full-body, athletic process. They call cyanotype a form of contact printing; one could thus also call it a deforming process.

I spent my first two weeks here wasting a lot of material and exposing unusable, even unspeakable, images. As it stands, I am thinking about using some of these cyanotypes as projection screens. There has been a project in my repository, either waiting or withering, which deals with sewers, hermits, and whores in the absence of light. The cyanotype is greedy for the sun, is made by it. But the divine blooms in darkness. So maybe my next move is to send this project on a date with my cyanotype screens.

To learn more about Cato Ouyang, follow them on Instagram and visit their website.