We live in a time when the conflict hums quietly in the background. Power travels silently – through cable wires, logistics chains, recommendation algorithms. What looks like stability often masks the violence that props it up: diffused, procedural, financed.

Li Yu’s work echoes this timely themed stillness that we are all living inside. In colors that are calm and materials that are neutral, Li Yu’s work stages the systems we inhabit without pronouncement. In the form of tension, her sculptural practice doesn’t enact violence; they absorb it, concentrate it, hold it in place.

Her latest work Contact I (2025) occupies the wall with a width of 170 cm. It is crafted from dark teak, iron-oxidised and varnished to a high polish. The surface recalls antique gun holders – lacquered, ceremonial, worn smooth through repeated touch… aged through use.

In a form of assembling motifs from Assyrian sculpture panels, there’s an implied motion packed to this encounter – a battle between a weapon and monstrous pawls, the warriors of the empire and external invaders. In a form of 3 dimensional collage and positioning, Contact I holds a shape of a gun as a whole with the dynamic hovers between states: weapon and monster, controller and controlled. Power shifts within it, never settling.

Contact II (2025) continues this inquiry with a more visibly directional structure. Taller and narrower. Its metallic surface appears worn, compressed, and tired. One end connects to a handle, the other into a mass of distorted, decorative debris. This dynamic invites the viewer into an imaginary act of participation – as if reaching, lifting, or offering. The gesture alludes to the historical asymmetry of power: a scene of tribute or enforced handover, like a performance inherited from empire – tributes to kings, subjects to rulers. In this choreography, Contact II, as a structural echo to historical events, becomes the site through which power is made interchangeable with the audiences’ “participatory”.

Both works reflect broader theoretical currents in Yu’s practice, where questions about the formation of historical authorship are inseparable from narrative control. Authorship, in her work, is not neutral.

At the same time, Contact I and II frame power not as an active force, but (pre-)condition. By slowing it (active force) to a near halt (stillness). Here, power is not performed in spectacle but embedded in postures, gestures, and the delay of action. Stillness, in her hands, becomes complicit in their quiet perpetuation. It is this complicated stillness – often mistaken for peace – that her work so carefully expands upon.

This tension continues in Li Yu’s language-based works, where the political register not through overt themes but through mundane tools and habits – those we grow up with, practice with, and rarely question. If Contact I and IIripped off the mask from the inheritance of imperial legacy, her pieces like Pronunciation Practice (2022), Listening Practice (2023), and In Other Words (2023) move inside that structure to reveal its daily operations. Here, history isn’t monumental. It is quietly inherited, rehearsed, embedded in objects as seemingly benign as a cassette tape or a workbook. These works reframe familiar tools of childhood not as innocent artifacts, but as conduits of institutional pressure. What looks like learning becomes rehearsal for hierarchy.

In Listening Practice (2023), cassette tapes loop broken phonemes spoken by a parrot – a voice mimics a language it was never meant to speak. The mimicry feels familiar to anyone who has repeated phrases in a second-language classroom or trained their tongue to carry a foreign cadence, Using real recordings from a parrot named Einstein—sourced online and categorised by theme—foods, greetings, instructions. The work frames the parrot’s mimicry not simply as repetition, but as something shaped by its conditions: trained, rewarded, and put on display. The cassette format, once a staple in English learning, here becomes a medium through which the animal’s rights and its communicative agency are staged in relation to the human listener. The parrot becomes a metaphor for individuals within systems—learning to speak through structured feeding, commands, and feedback loops.

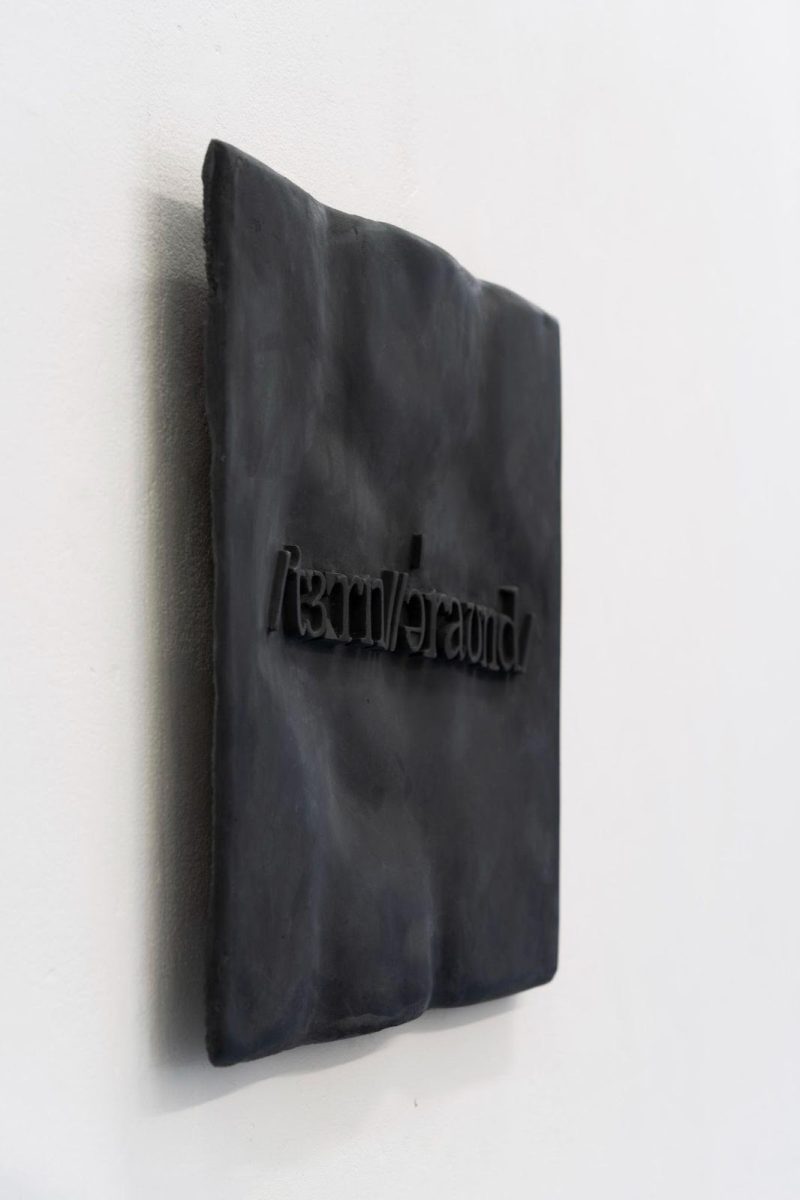

In Other Words (2023) takes the form of instruction panels, where commands such as “turn around” and “here” are rendered in hand-embossed phonetic symbols. These inscriptions are visually ambiguous and imprecise, slowing comprehension. Yet, once decoded, they are undeniably directive. This work shares a kinship with Pronunciation Practice – both reflect on how language is absorbed not only as knowledge but as command. While Yu’s experience learning English in the UK offers one entry point, the deeper question lies in how systems – be they pedagogical or social – use language as a tool of alignment, shaping not just what is said, but how one learns to respond.

Yu holds these fractured gestures in suspension, asking how meaning is shaped when communication is learned through repetition and reward. These works look at language as structured by power: who speaks, who listens, who corrects, who is corrected. Language, in Yu’s work, becomes a slow revelation of geopolitical asymmetry: not what is said, but what cannot be fully said. Even a simple sentence becomes a site of asymmetrical access: to meaning, to clarity, to belonging. She probes the soft violence of pedagogy, especially in postcolonial contexts where fluency in a dominant language is tied to opportunity, legitimacy, and belonging. Her works expose how the everyday can act as a vessel for political asymmetry, making visible the quiet mechanics of compliance and the inheritance of linguistic subordination.

Today, we live in a time where the mechanisms of control are quiet, distributed, and often aestheticised. Power no longer always announces itself through rupture; it settles into form, into protocol, and sinks into our interfaces. Against this backdrop, the work of Li Yu has its urgency to be reflected. They do not interrupt the noise, but slow it to a frequency we can begin to hear. Her practice reminds us that what appears stable may be most dangerous when it resists interrogation – that silence, neutrality, and stillness can carry the weight of entire histories. And perhaps the question is not whether we are caught inside these systems, but whether we have learned to notice when they speak.

MORE: @liiiiiiiyuu_ & @helloo0dump